Two years ago, I coached a nearby high school debate team. When my students needed to research using databases LexisNexis or JSTOR, I gave them my EID and password. Try to say no to a high school student who wants to learn about political capital and budget negotiations — it’s almost impossible. Skirting copyright law so that a few 16-year-olds could peruse databases was worth the risk, and I doubted that my actions would devastate any major New York publishing conglomerates.

While I was illegally providing students with academic articles, Aaron Swartz, co-developer of RSS, an Internet feed system, and co-creator of Reddit, a popular link-sharing website, was also breaking copyright law with plans to share academic materials on a larger scale. Swartz, a crusader for open access to academic materials, claimed that students, faculty and others with the privilege of access to databases had “a moral imperative” to share information with those who don’t have access. As a result, he faced criminal charges for downloading four million articles from the database JSTOR on MIT’s campus with the intent to upload them to file sharing websites.

On Jan. 11, facing up to 35 years in prison and $1 million in fines, the 26-year-old Aaron Swartz killed himself, sparking energetic debates about information ownership and the criminality of sharing.

The growth of digitized books and articles alongside the popularity and ease of file sharing has posed unique challenges to both universities and the publishing industry. Fred Heath, director of the University of Texas Libraries, says that over half of the libraries’ budget for resources — amounting to several million dollars — is dedicated to electronic materials. Much of that money is dedicated to database access with heavy restrictions on sharing.

At UT, library visitors have certain limited privileges: Scholars can look at archival materials at the Harry Ransom Center and Texas residents can apply for library cards, for example. But online materials are much more restrictive: Visitors cannot access online academic materials unless they have obtained a visitor EID with a government-issued photo ID and are logged on to a computer in a UT library. Then, if visitors decide to share those articles, email them or make them available to the public, they could face federal copyright charges. According to Heath, “We, like MIT, are obligated to protect the intellectual property that we are obtaining.”

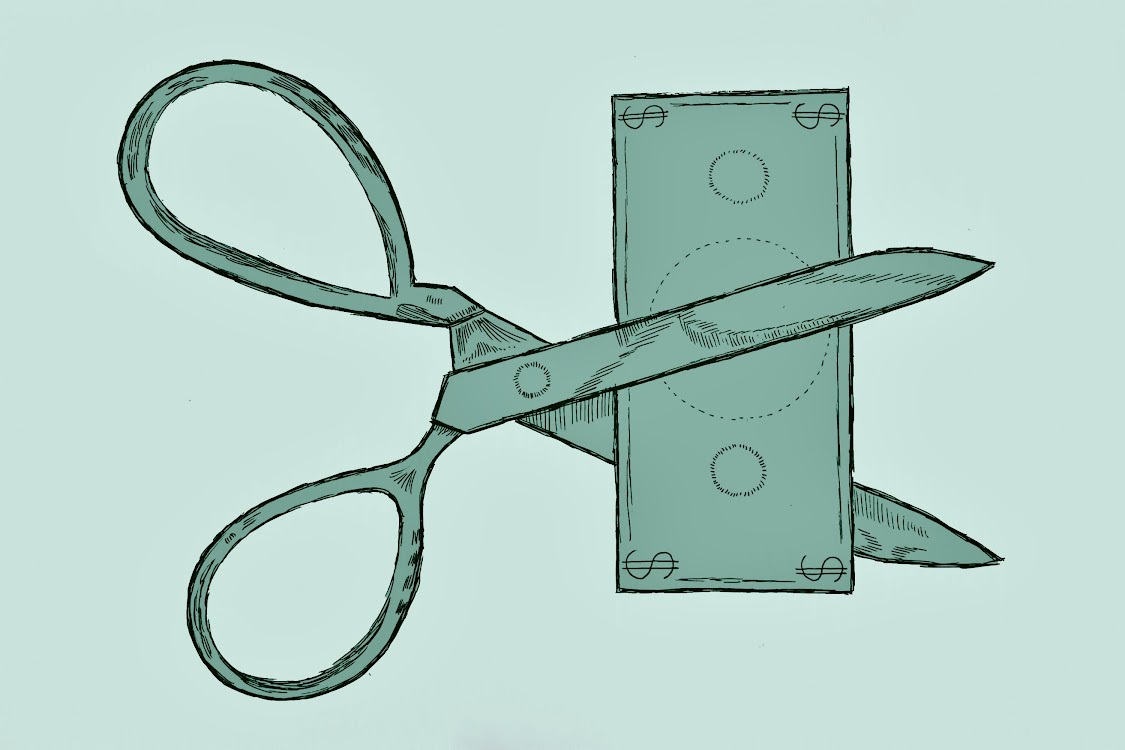

That seems fair — the authors of articles work hard, companies like Taylor & Francis pay to print journal issues and databases must charge institutions if they want access. But the process is less straightforward. The vast majority of peer-reviewed academic journals do not financially compensate the authors of submitted articles, unlike books or other publications. Scholars are expected to publish in order to get tenure, so authors are willing to share their research for free.

Publishers aren’t so generous. Without a university affiliation, purchasing a single issue of an academic journal will cost several hundred dollars on average. In some cases, if an article’s author wishes to republish the article in a book, that scholar must pay hundreds to the publisher to recover some of his or her ownership rights.

Meanwhile, copyright restrictions seem only to become more austere. Over the past 100 years, copyright protection terms have been lengthened 12 times and never shortened. Philip Doty, associate dean of UT’s School of Information, said in an email, “The stakeholders invariably ignored in many copyright policy discussions are the general polity, that is, the persons for whom the copyright clause in the Constitution was developed to protect.” In other words, the same laws that lock the general public out of academic research were created to protect their ability to eventually access others’ work.

Fortunately, academics have some recourse. Efforts like Creative Commons — another organization that Aaron Swartz helped to create — aid researchers and academics in retaining legal ownership over their work, even if they donate it to a for-profit publishing company. According to Georgia Harper, the University’s scholarly communications advisor, a Creative Commons license “allows anyone with an Internet connection to use [the article] in the ways that most scholars would be happy to have others use their work.” Likewise, Dr. Doty advises scholars seeking freer access to their work, “Sign only those contracts to publish that grant the rights holder, in this case, the creating academic, the right to publish the material either in an institutional repository or on a personal website as well as to develop derivative works.”

Not surprisingly, the individuals with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo are publishing conglomerates and their shareholders. Most of the population remains shut out of even publicly-funded academic research. Most students will be, too, when they graduate. But with growing opportunities to share research more openly, a shift toward open access seems inevitable, absent draconian copyright expansion. I hope the Aaron Swartz case is a mistake that we learn from rather than a harbinger of harsher punishments.

San Luis is a Plan II and women’s and gender studies senior from Buda.