Like George R.R. Martin’s great wall or Ernest Hemingway’s endless sea, a partition divides the world of fiction.

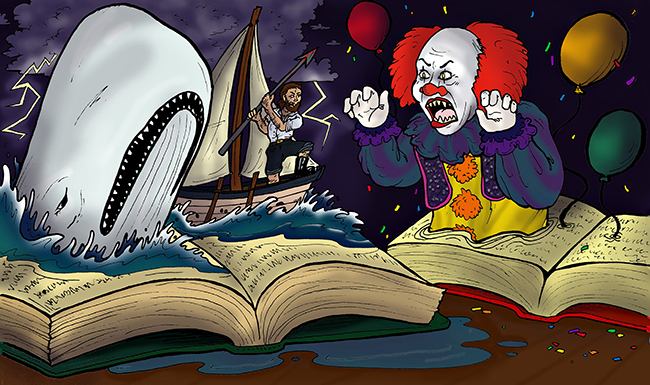

On one side is genre fiction: Plot-driven and emotional, genre often contains unseen forces of evil or forbidden romance. Prolific authors such as Stephen King and Stephenie Meyer saturate this category with evil clowns, vampires and dragons. Literary fiction is on the other side — often containing characters not so different than its audience. Authors of this persuasion, such as David Foster Wallace or Donna Tartt, write about everyday life — grief, family and depression.

The common argument against the literary-genre split is that it makes literary fiction highbrow and genre fiction lowbrow. The issue is complicated, an argument decades in the making with major publications and authorial opinions falling on both sides.

Although English professor Gretchen Murphy reads mainly academic work, she said she occasionally picks up genre fiction. When she read “The Hunger Games” a few years ago, she said she couldn’t put it down, although it lacked the intellectual stimulus that literary fiction inspires.

“I think most people who study literature see it as a debate, rather than something where there’s a firm answer,” Murphy said. “But people may believe in that line, even if they’ve been exposed to arguments against it. [The distinction] has to be useful in some way, to tell audiences, ‘If you like this book, then you may like this other one.”

English senior Laura Hall said she doesn’t understand what makes certain books literary and others genre. “Frankenstein,” she said, is considered literary fiction, yet follows a genre plot: an emotional protagonist fighting an undead monster.

“Isn’t ‘Frankenstein’ kind of sci-fi?” Hall said. “‘Dune,’ I think, is literary, even though it’s put in the sci-fi section. It spans other stuff, too — spiritual things. ‘Lord of the Rings’ is put in literary probably only because it’s the most famous fantasy book.”

Hall, a reader of both styles, said she is bothered when peers consider genre fiction less intellectual simply because of its label. English associate professor Elizabeth Richmond-Garza said “Frankenstein” was released long before the literary-genre fiction debate began, and its original critical reception and antiquity have prevented the book’s switch into genre fiction.

“Individual genre works are allowed to be taken seriously often because of a specific history of a critic taking them seriously,” Richmond-Garza said.

Conversely, she said, today’s society views sentimentality in a negative light. The more emotional a text is, the less seriously it will be taken. Genre fiction is defined by emotion, romance and the outstanding.

“The elaboration of fantastical or frightening worlds and plots is seen as crass and appealing too much to readers’ desire for sensation,” Richmond-Garza said. “Rather than restraint and intellect, genre works evoke emotional responses and merely aim to thrill the reader.”

Richmond-Garza said that a text’s popularity counts against it. The more popular a work is, the more skeptical intellectuals and academics become.

Hall said she sees the split as a good thing: Genre fiction is a means to connect people, and literary is a way for academics to determine intellectual value.

“I have yet to be in a class where someone didn’t admit they like ‘Harry Potter,’” Hall said. “But, English is a laughable-enough major. People want to take it seriously.”