Sexually transmitted infections are scary enough without the added risk of developing cancer, yet this is exactly what we face with human papillomavirus, better known as HPV. Luckily, there is a vaccine. But it is underutilized by college students. Men especially need to realize medical safeguards available to them, for their own health and their partner’s.

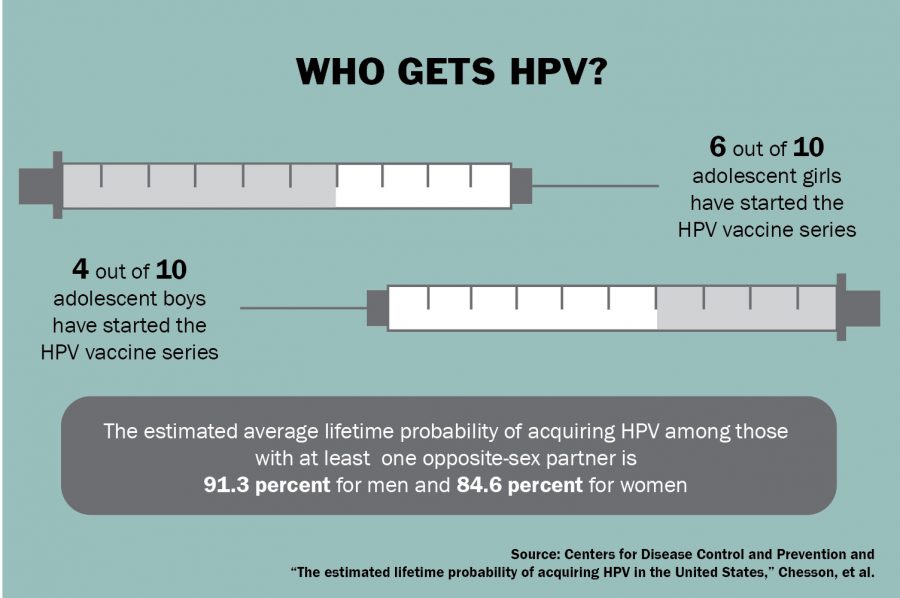

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. The CDC predicts that more than 90 percent of men and 80 percent of women will be infected with at least one type of HPV in their lives. Most cases resolve themselves, but when the virus persists, results are often deadly. HPV causes virtually all cases of cervical cancer, 95 percent of anal cancer and about 70 percent of throat cancers. In addition, some strains of the virus cause genital warts.

The high rates of cervical cancer caught the attention of researchers back in 2006, prompting the Food and Drug Administration to approve a vaccine for women. There was already considerable evidence linking HPV to cervical cancer, so health care professionals focused on women’s HPV risks, neglecting men’s.

The men’s HPV vaccine received FDA approval in 2009, but by then the vaccine had cemented its popular reputation as a “girl’s” vaccine that had little relevance to men. A CDC study found that not enough boys had gotten the vaccine, with 24 percent of parents citing that their health care provider had not recommended it. This shows a lack of understanding at multiple levels of the health care food chain — we view men less at risk than women for HPV, yet this is simply not the case. Men also face increased cancer risk, especially within the throat.

“Any effort to increase uptake in the vaccine in men and women is to really get the word out that this is a vaccine that prevents cancer,” said Charlotte Katzin, nurse manager in the University Health Services’ allergy immunization clinic. “These cancers are sexually transmitted, but it is cancer nonetheless.”

If you won’t get the vaccine to protect from cancer, do it for the sex. On a college campus where hookup culture reigns, the removal of one STI from the equation is significant. Protecting both yourself and your partner from cancer and genital warts is a potentially lifesaving precaution.

“If you really care for [your partner], then I think you should do it to protect cancer for them,” human biology sophomore Amer Mughawish said. “Even if you’re a carrier, it’s good to take the vaccine so you can help your partner to not get it.”

Increasing vaccination rates for HPV should take a multifaceted approach. The University could distribute more information on the vaccine during orientation programming or through health announcements. The dissemination of information to parents through parent associations would also be valuable, as they are often the ones checking in with students on their health.

However, all of this takes a backseat to student involvement. Men and women alike need to recognize the deadly consequences of HPV and urge their partners to get vaccinated. No one wants an STI, and everyone can get behind cancer prevention. The miracle vaccine is here — students just have to use it.

Hallas is a Plan II freshman from Allen. Hallas is a senior columnist. Follow her on Twitter @LauraHallas.