It’s savior season. As classes end and students have several free months, many will choose to go on medical mission trips abroad. While students have the best of intentions for these trips, a critical eye is crucial to ensuring that students help and empower, not hurt, a foreign population.

“The Western savior idea, the idea that any kind of health care is good healthcare is a false assumption,” humanities senior Christle Nwora said. “We can be damaging by putting our views on other people and our social feelings about what health looks like.”

Many low-income countries lacking in medical infrastructure allow pre-health professions students access to many patients who are in need. However, when students are allowed to treat patients without proper licensing and supervision they endanger patients’ lives, which implies that some patients’ lives are more valuable than others’.

“In the US we don’t let our nursing students just go off by themselves, we have someone supervising them,” said Shalonda Horton, assistant professor of clinical nursing.

However, the environment of medical missions offers much more room for a student to give medical advice unsupervised.

“You don’t want to have misinformation that causes harm once you’ve left that country,” she said. “And then you don’t want that young person thinking ‘I did the right thing.’”

A medical mission trip still seems like a great experience and resume addition — students are still globally engaged. But admissions officers at medical schools know what responsible healthcare looks like, and student medical missions often don’t fit the bill. Instead, providing certain medical treatments as an unprepared undergraduate shows questionable judgment on the part of an applicant and a legal liability risk on the part of the college or study abroad program. The combined result is medical schools denying admission to well-meaning applicants.

“No one ever goes with the idea that I’m going to exploit these people to prop my resume for med school or nursing school,” Nwora said. “I just think sometimes we don’t have the processes in place to prevent us from making those ethical missteps.”

Embarking on a responsible mission trip requires serious self-reflection and objective analysis of the traveling organization. First and foremost, medical advocacy groups need licensed staffs with physicians or nurses. Second, the program must be sustainable and involve local medical communities — they are the ones who know what their population needs and will continue care once the mission group has left. It also helps if students have a shared cultural background or long-term interest with the region, making communication more efficient.

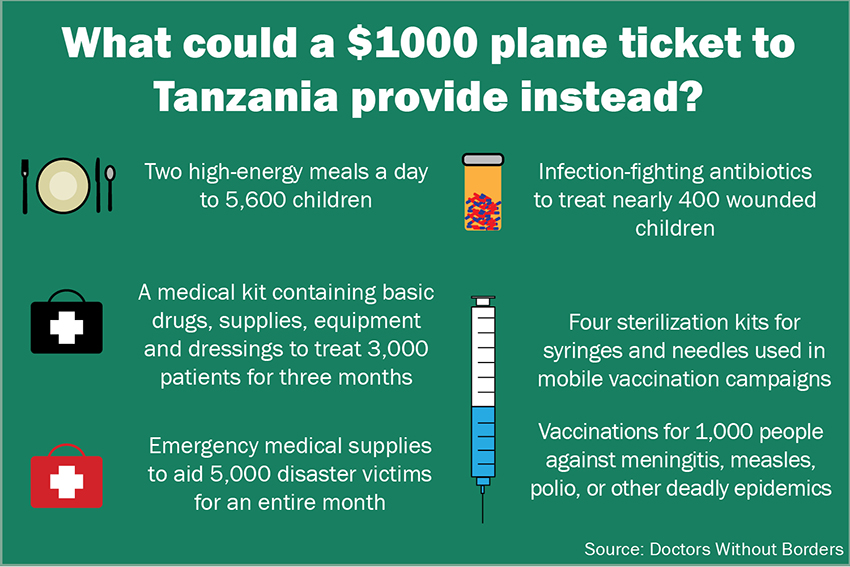

For untrained students, going abroad may not even be the best way to help. Instead, they may be better placed to conduct research about a particularly global health issue under a professional or simply donate funds that would be otherwise used to travel to established global health groups like Partners in Health or Doctors Without Borders who work to empower local medical communities.

Acting on one’s own limitations is not a comfortable or easy process, but good intentions don’t make up for harmful

medical realities.

Hallas is a Plan II freshman from Allen. She is a senior columnist. Follow her on Twitter @LauraHallas.