Only 36 percent of Americans regularly read science news, according to a study conducted by the Pew Research Center. Four in 10 adults are dissatisfied with the way that science is communicated to the public, particularly the sensationalism of science.

Headlines like The New York Times’ “Dogs Can Detect Malaria. How Useful Is That?” display this sensationalism that frustrates the public.

Neuroscience junior Sarah Campbell studies how storytelling plays a role in science communication. Campbell said sensationalist science journalism provides an alternative for science news that can often be dull.

“Most of science news can be utterly boring — in reality, it’s a slow-moving behemoth,” Campbell said. “It takes a long time to reach concrete conclusions, and the full story isn’t something that would engage the average reader for a very long time. As consumers of science reporting, we prefer self-enclosed stories with a point, and sensationalist journalism fits the bill.”

David Hillis, professor in the department of integrative biology, said the miscommunication between scientists and reporters can also contribute to the sensationalism of science.

He said there are two main reasons for this miscommunication. First, scientific research is often reported to the press through public relations departments, which try to emphasize the potential future relevance of research to the public.

A second miscommunication, Hillis added, often happens when reporters attempt to translate, or interpret, scientific results to a lay public.

“It is often hard for scientists to control or correct articles in the popular press,” Hillis said. “Scientists should strive to use simple but accurate language in talking to reporters about their research to minimize the degree of ‘translation’ that is necessary.”

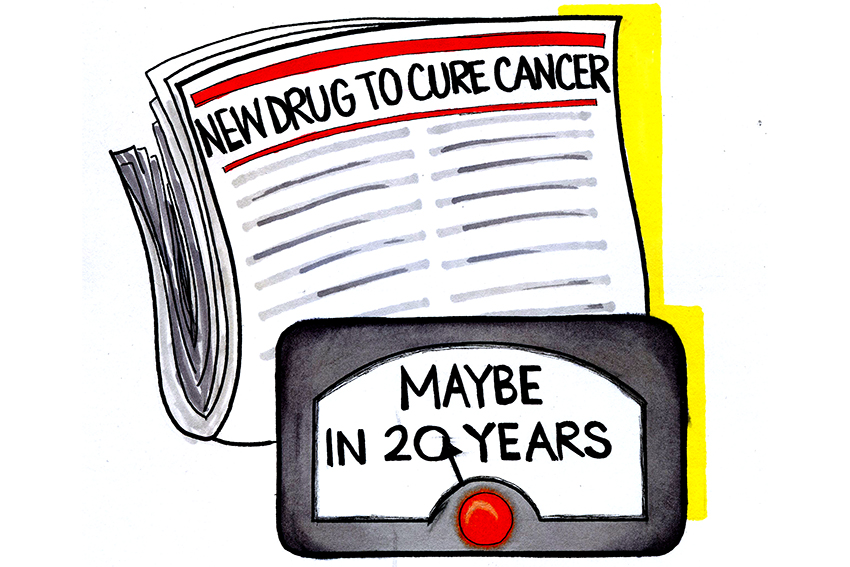

A Effective Clinical Practice study noted that a common example of science sensationalism occurs in reporting cancer. Hillis said this is largely because the public does not understand that cancer is not one disease that has a single, possible cure.

Science has made enormous progress in finding effective treatments and cures for various types of cancers, Hillis said, but any given treatment or drug has specific, limited uses and applications.

“Both scientists and reporters have an obligation to make this clear, but it is much easier and more dramatic to say ‘This drug will lead to a cure for cancer’ than to say ‘This drug may eventually be useful in treating certain specific conditions and types of cancer,’” Hillis said. “The former statement gets more people to read an article, but it is almost certainly misleading.”

This distortion can also lead to the mistrust and misunderstanding of science, said Hillis.

“Science is based on accuracy,” Hillis said. “When scientific findings are distorted or exaggerated, then the public can lose trust in science and become misinformed about scientific advances. Those are opposite of the goals of science.”

To alleviate this issue, it is important to understand that while brevity and simple language can maximize public understanding, they can also falsely educate the public if accuracy is not emphasized, Hillis said.

“I think scientists need to learn to use simpler, but still accurate, language in talking to the media and the public, and that reporters need to understand that sometimes detail and specifics are critical to the accuracy of a story,” Hillis said. “At every step, both scientists and reporters need to work to ensure that science is not sensationalized or exaggerated.”

Both Hillis and Campbell said ultimately, scientists and journalists must work together to address these issues.

“When both parties have a good understanding of the nature of each other’s work, scientists and science communicators can create a better environment for quality journalism,” Campbell said.