“I couldn’t go back. I couldn’t.”

June 27, 2019

In her 18 years of teaching sociology full time at UT, senior lecturer Penny Green rarely missed a class. That remained true until the Thursday before Spring Break this year, March 14.

It was the early afternoon, and Green was walking across campus to her second class of the day. As she walked, she started to notice something was wrong. She needed to go to the emergency room.

“I didn’t realize how serious it was, but I knew I couldn’t see them right then,” Green said.

Green dismissed her class, saying she expected the issue to be cleared up by the afternoon, then went to a hospital nearby. There, she discovered she needed major emergency surgery, was relocated to another hospital and then moved to an intensive nursing facility. What Green expected to last a couple of days turned into a process that took over four weeks.

Green still planned on returning to campus, but just a week after being admitted to the second hospital, her husband of 46 years died unexpectedly at home.

It was then she decided she couldn’t return to class for the rest of the semester.

“You don’t want to do it, but I couldn’t go back. I couldn’t,” Green said. “At UT, you have to be able to hit the ground running, and I could walk, but I could not hit the ground running.”

Sick Leave

A Texas statute gives state employees such as UT faculty and staff eight hours of paid sick leave for every month they work. These hours accumulate, which means the longer they work at the University, the more hours they accrue.

Green accumulated over 40 weeks of paid sick leave during her time at UT, equivalent to an entire school year. She never used it until last semester.

If an employee or their immediate family member is suffering from a “catastrophic” condition requiring long-term care that would “exhaust all leave time earned,” that employee would be eligible to use the Sick Leave Pool, according to UT policy.

The Sick Leave Pool is created through donated sick leave hours. Employees can receive up to 720 hours, or about four and a half months of work, from the pool.

“You know in this case you’re contributing to your fellow coworkers, and you know a lot of people are of the belief that what goes around comes around,” said Adrienne Howarth-Moore, the associate vice president and chief officer of UT’s Human Resources Department.

Thirty employees used paid sick leave pool in the spring, totaling 7,676 hours. The pool currently has 2,090,575 hours available, Howarth-Moore said.

Employees can also donate their accumulated time to others directly. After those resources are exhausted, the University is required to provide up to 12 weeks of unpaid sick leave through the Family Medical Leave Act.

“We allow you to exhaust all your leave options, then we have to start thinking about whether or not it’s feasible for you to return to work,” Howarth-Moore said. “At some point, we do have to make decisions that, if you’re just unavailable for work, maybe separation from employment is the next phase.”

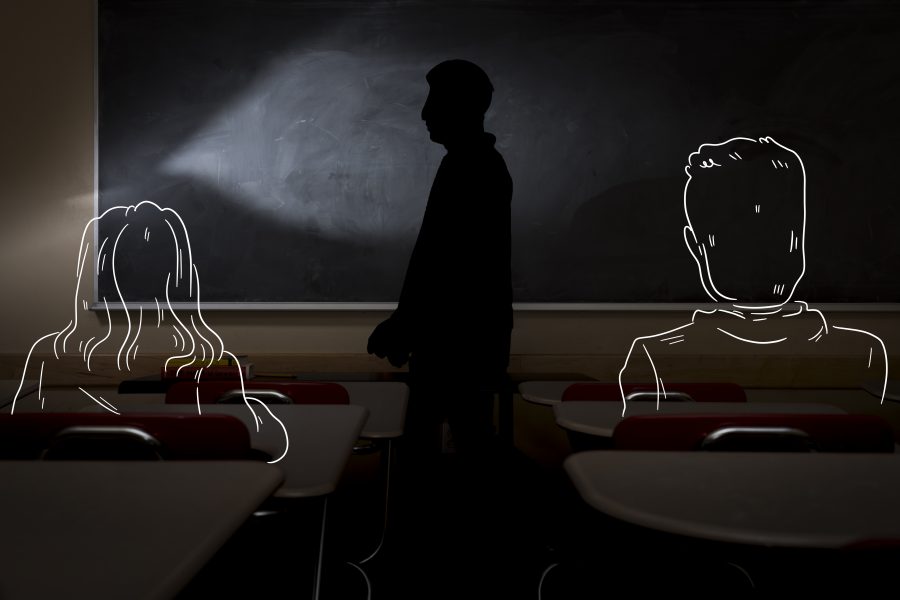

What Happens to The Classes

Once news of Green’s situation reached campus, it became the department’s job to handle her three courses: an introductory sociology course, an undergraduate seminar and an honors course. Sociology department manager Julie Kniseley and department chair Robert Crosnoe were in charge getting a replacement instructor as quickly as possible. That required asking other faculty members to take on more work.

“I’ve been working at UT for almost 10 years, and we’ve had several faculty members become ill, and we’ve always found someone,” Kniseley said. “People are very generous and willing to help in these situations.”

Mehdi Haghshenas, a senior lecturer in the sociology department and close friend of Green’s, was one of several faculty members who took over her classes while she was gone. On top of his own three classes, he managed her honors seminar for the rest of the semester and helped with the introductory course.

“Even though I had three other courses and other responsibilities, I felt this was a very great duty,” Haghshenas said. “I take this kind of responsibility really seriously.”

Haghshenas and others handled her classes for a few weeks before the department eventually canceled lectures for Green’s introductory course and undergraduate seminar. Green also made changes to the grading policy and dropped the last exam and writing assignment to ensure students got credit for the course.

Bringing in a new lecturer proved difficult for the introductory course. Teaching assistants are not allowed to teach courses by themselves, so the four TAs in Green’s introductory course helped the replacement lecturers, making sure they did not stray from the syllabus.

Chen Liang, one of the assistants, said in an email the TAs’ workload increased significantly, and they had to do tasks they traditionally don’t do, such as writing exam questions.

“The whole issue was the department didn’t foresee the possibility of someone leaving or ending the class in the middle of the semester,” Liang said.

Green said her department was crucial during the recovery process. Haghshenas was among the first people she called when she was hospitalized. She said faculty delivered the necessary paperwork to and from her recovery bed.

While she was in the hospital, her colleagues visited her and filled her hospital room with flowers.

“My God, my room looked like a florist’s,” Green said. “The amount of support I received from my department was unbelievable. They were absolutely wonderful.”

Green has now fully recovered. She returned to campus for the first two days of exam week to attend an honors colloquium where her students presented their findings. With no summer classes scheduled, she said she will spend her days relaxing and traveling.

“I just cannot speak highly enough of the way I was treated by my department,” Green said. “It went as smoothly as a very yucky situation could have gone.”