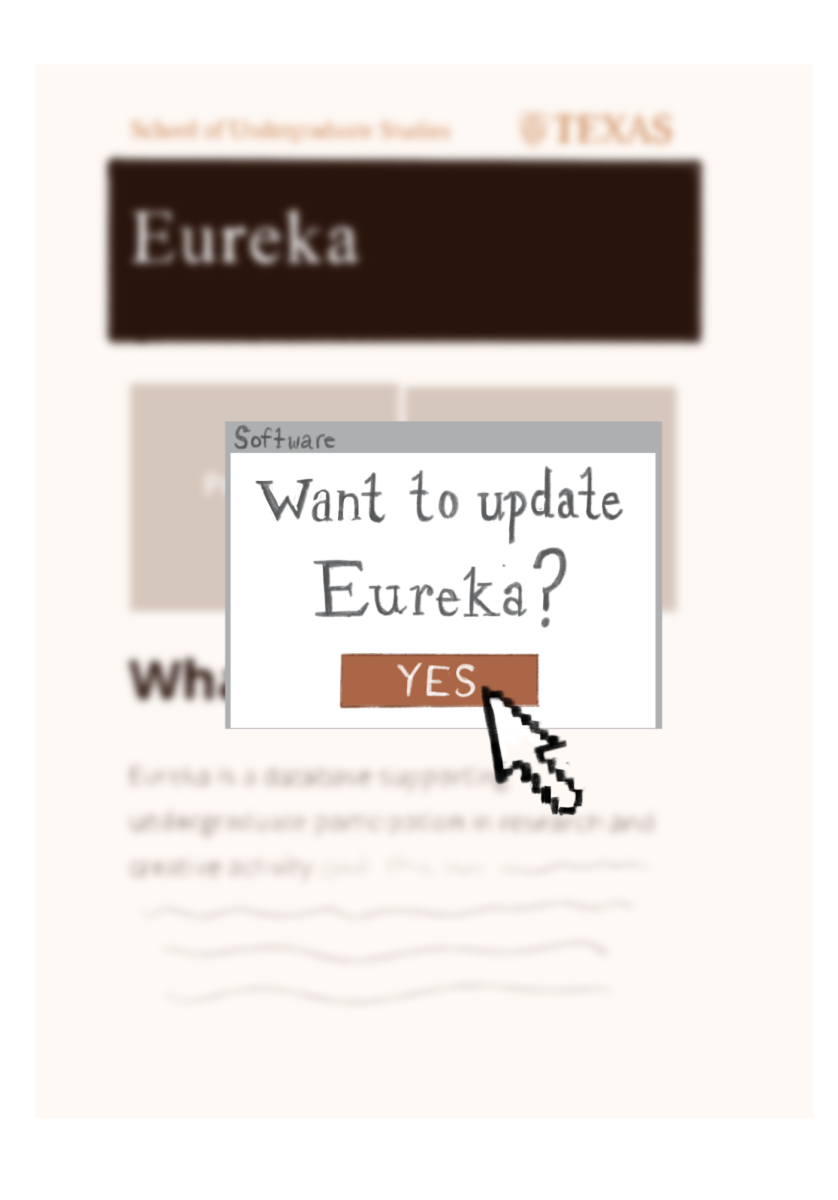

In a blistering Canvas announcement entitled “A Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day for Many of You,” John Kappelman ousted almost 70 students in a GroupMe for his online Anthropology 301 class. All members of the GroupMe were reported to the Office of the Dean of Students for academic dishonesty, regardless of whether they actively participated in sharing answers.

I know there are some instances where cheating is completely unambiguous. If you’re in the middle of a test and you excuse yourself to go to the bathroom where you immediately pull out your phone to look up a test question — you’re a cheater. If you copy down a classmate’s response to an individual assignment word-for-word and try to pass it off as your own work — you’re a cheater.

But what about a person who joins a group chat on the first day of class in hopes of finding a study group or making some friends? What about students who don’t partake in the sharing of answers and exam questions, the honest students who just need a resource to turn to when they’re confused? Are these people cheaters?

I say they’re not.

I would even go so far as to say that professors do a disservice to their students when they uphold UT’s more ambiguous academic dishonesty policies.

For example, Government sophomore Hector Mendez faced similar consequences for academic dishonesty as the students in Dr. Kappelman’s class. After a classmate posted the answers to an online quiz in his history class’s GroupMe, Mendez and his classmates rushed to leave the chat so they wouldn’t be caught up in a cheating controversy. However, he soon found himself without a support system in that class. “In previous classes, group chats were definitely very helpful for me, especially when I was struggling because I could find other students who could explain the problems to me,” Mendez said.

The most common charges levied against students accused of academic dishonesty are “providing or receiving aid or assistance” and “collusion.” But to me, these words just seem like synonyms for collaboration and group work, which is exactly what one student claims was actually happening in the GroupMe for Kappelman’s class. Students merely guessed at what would likely be on the exam. Had anyone actually shared exam questions or answers, I would totally understand the consequences. However, this is not the case.

Electrical engineering and neuroscience sophomore Sai Koukuntla finds that group work is an incredibly important part of his job. As a student technician at Applied Research Laboratories, Koukuntla collaborates with colleagues at every stage of any project he’s working on.

“No one’s doing their own thing, so you all kind of have to work together. There’s nothing that you have to do by yourself,” Koukuntla said. His classes are a different story altogether.

“Some professors compare homeworks with each other to see if anyone worked together, and I don’t think that’s realistic because virtually no job would make you do everything by yourself,” Koukuntla said.

Neuroscience department chair Michael Mauk agreed.

“If you talk to employers, they all say the same thing: One of the most important attributes we need out of people is the ability to work in groups,” Mauk said. “The real world tells us we need people who can work with others.”

As such, Mauk tries his hardest to make his classes collaboration-friendly.

“My own personal view is that most of the grade should be based on exams and homework shouldn’t have much of an impact on your grade, to encourage (collaboration) instead of outlaw it,” Mauk said. This makes cheating a black and white issue, removing penalties for students who collaborate on class assignments simply to facilitate their own learning.

Of course, I agree that cheating is absolutely wrong, and cheaters should face the consequences. However, when the University and professors prosecute students simply for working together, it sends the incorrect message — that learning and progress happen in a vacuum. In reality, academic growth is a journey, and all journeys are better with friends. Students should be able to depend on one another as a learning resource which is only possible if professors consider limiting assigning strictly independent work.

Dasgupta is a neuroscience sophomore from Frisco.