Students reflect on a year of increased violence against the AAPI community

April 30, 2021

Trigger warning: This story contains mentions of racism, hate crime and violence against Asian people. For a list of Anti-Asian violence resources look here: https://anti-asianviolenceresources.carrd.co/

Growing up in the predominantly white town of Tomball, Texas, Hana Thai’s classmates sometimes made comments like, “You’re really pretty for an Asian,” and, “You’re really pretty for a hijabi.”

She didn’t process the racist comments about her Vietnamese heritage at the time, but had read headline after headline about hate crimes against Muslims and Asians for years.

Hate crimes against the Asian American and Pacific Islander community increased by nearly 150% in 2020.

Now, when Thai reads about the violence, she turns her phone off. She said it feels like she’s reliving her own trauma.

“I want to be upset, and I want to be angry, and I want things to change,” said Thai, international relations and global studies sophomore. “But I’ve been (dealing with) this for so long now that I don’t have the energy to continuously be angry … upset or scared or frustrated.”

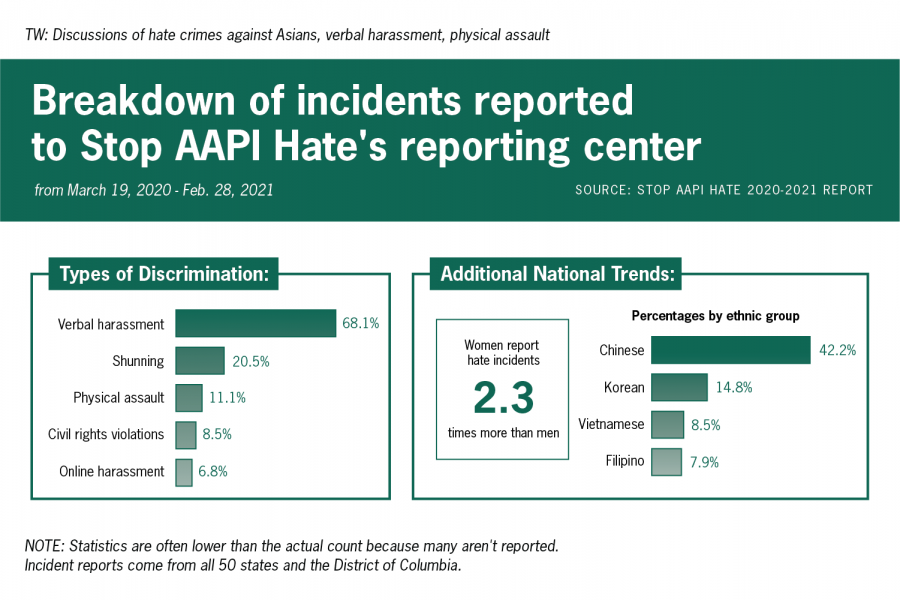

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, Stop AAPI Hate has reported 3,795 incidents of discrimination. In the wake of the recent violence, some members of UT’s Asian community reflect on lifelong instances of hate, racism and microaggressions directed towards their community.

When people make fun of Jackie Cheng’s name, or ask, “Where are you from?” she said she typically ignores them. But Cheng, an international relations and global studies and sociology freshman, said the increase in hate crimes made her reflect on racism that she and other Asian women have experienced.

In 2020, Stop AAPI Hate received 2.3 times more reports of violence against women than men. Time magazine reports Asian women have experienced decades of fetishization, rooted in the objectification and hypersexualization they experienced during their initial immigration to the U.S. in the late 19th century.

The New York Times reported the gunman at the March 16 Atlanta shootings admitted he targeted Asian massage parlors to eliminate his “temptations.” Eight people, six of whom were Asian women, were killed in the shooting. In conversations about the shooting on social media, Cheng said she continued to see posts fetishing Asian women. She said the media she sees about other Asian women influences her perception of herself.

“I sort of see myself as though I’m an object in other people’s eyes,” Cheng said. “Is that all I am? Am I just an object for them to fetishize? ”

Tony K. Vo, assistant director of the Center for Asian American Studies, said society deemed Asian American populations as the “model minority” in the 1960s in response to the Civil Rights Movement led by Black Americans. He said this myth was fabricated to drive a wedge between Asian Americans and other marginalized groups.

Now, as reports of violence against Asian American and Pacific Islanders grow, Vo said he sees the protections afforded to the AAPI community under notions of the model minority myth fading.

“A lot of (Asians) were like, ‘If I was just a good person, did my part, paid my taxes, kept my head down … as I moved through America, no one (would) bother with me,’” Vo said. “Now none of us feel that way. We’re all anxious.”

As a Vietnamese Muslim woman, Thai said the Atlanta shooting felt reminiscent of other hate crimes against her religious community, such as the Christchurch shooting in New Zealand, which killed over 50 Muslims in March 2019.

“I am a part of so many groups that face such discrimination and hatred and violence on a daily basis that it feels kind of hopeless at times,” Thai said.

Vo said the University should invest in their Asian students by building an inclusive Asian community on campus and hire more Asian staff and faculty. Currently about 20.2% of UT’s student population is Asian, only 11% of professors and 7.43% of staff are Asian. Five percent of Texans and 8% of people in Austin are Asian.

Chemistry junior Grace Liu said this gap makes her feel underrepresented in the classroom. She said she’s more likely to speak up in classes with Asian professors rather than white professors.

“I’ve had a couple of Asian professors, and I’ve been very interactive with (them),” Liu said. “I feel more motivated to go to their office hours and try to strike a conversation with them. I tend to be quiet in classes that are led by white male professors as opposed to professors of color or Asian professors.”

Thai said she feels frustrated seeing people outside the AAPI community shocked about recent AAPI violence, when she has personally been affected by news of the violence her entire life. The calls to end violence come in waves, she said, and she’s afraid this wave of activism will fade like the ones before it.

“Our experiences are minimized,” Vo said. “It took an entire year of violence and hate language toward Asian Americans for the nation to address the issue and convey care to our community.”

Liu said she feels more comfortable talking about racism with her fellow AAPI peers, but she encourages non-AAPI students to attend university workshops to continue the conversation about ending violence toward the AAPI community.

“Racism directed toward us is something that we can all relate to, but at the same time, being able to understand each other and empathize with each other strengthens that bond among all of us,” Liu said. “Even though it’s painful, it’s definitely something that should be talked about.”

As a community facing violence, Thai said many in the Asian community want one thing: to exist safely without fear of violence.

“I shouldn’t have to tell people that I deserve to exist safely, no matter what I identify as,” Thai said. “Everybody just wants to feel safe. Everybody just wants to feel like they’re being who they are isn’t going to put them in danger.”