Risky behaviors, such as drunk driving and unprotected sex, are caused by decreased self-control functions in the brain, despite prior beliefs that it was people’s desires that caused risk-taking, according to University researchers.

Sarah Helfinstein, postdoctoral integrative biology researcher, conducted brain activity studies using data collected at the University of California, Los Angeles. According to Helfinstein, most other risk-related studies focus on brain responses to different levels of risks, while her research focuses on brain activity before a risk is taken.

“Even though the actual risk itself is the same, what the difference is, when you take the risk or when you don’t take the risk is activation in [self] control regions of the brain,” Helfinstein said.

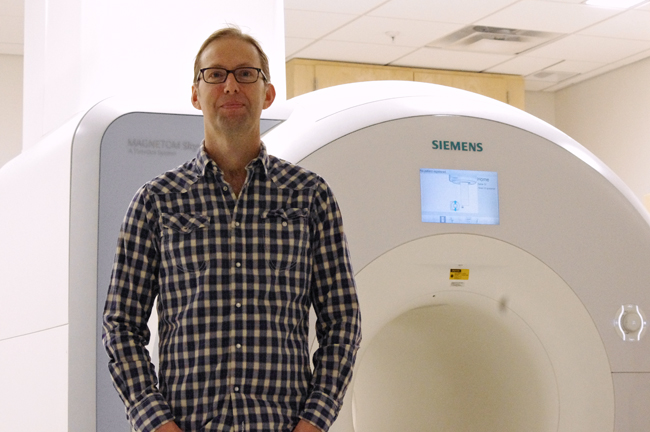

Tom Schonberg, researcher in the Imaging Research Center at the University, said people don’t know whether a risk is beneficial or harmful until after they have already taken the risk. Schonberg said to study risk prediction further, focusing on brain activity right before a risk is taken is vital.

“The unique part of what [Helfinstein] did in this study is to look at what happens one step before deciding whether to stop or go on; before you know what is going to happen,” Schonberg said.

Russell Poldrack, director of the Imaging Research Center, said after years of brain function and control research, these analyses of the data are being used to help further understand the decision-making behind risky behavior.

“The goal of the project [is] to help us understand the brain systems that are involved in memory, executive function and control, risky behavior and how they all relate to each other,” Poldrack said.

The conclusions that researchers drew from these studies can be implemented in many different areas, according to Helfinstein.

“It helps us understand better why people choose to take or not take health-relevant risks [like] smoking cigarettes, experimenting with drugs or having unprotected sex,” Helfinstein said.

Poldrack said the implications of this research could be much bigger in the future, and conclusions from these studies could affect the treatment of mental illness and the prediction of future criminal behavior.

“It is certainly relevant to some of the disorders in which people are known to take impulsive risks, like ADHD or, particularly, bipolar disorder,” Poldrack said.

This is just one step toward understanding how people can avoid dangerous risks, according to Helfinstein.

“If we can move on to better understand how to strengthen [self] control systems when confronted with these decisions, it might help people,” Helfinstein said.