UT-Austin researchers discover oldest known Mayan calendar

January 16, 2023

A global research team partly consisting of UT-Austin scholars discovered direct evidence of the oldest known Maya calendar dating back to 300 B.C, much older than previously discovered fragments dating between 300 and 900 A.D.

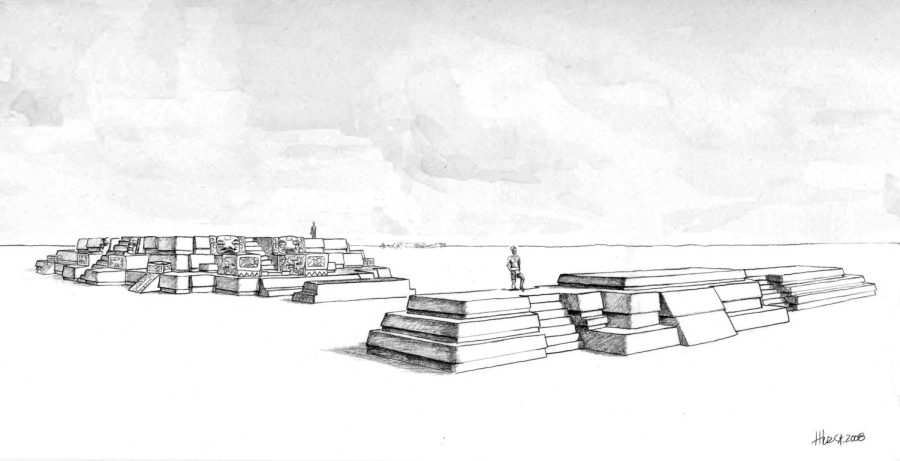

Pieces of painted plaster were discovered at an excavation site in San Bartolo, Guatemala. David Stuart, an art history professor and member of the team who made the discovery, said the San Bartolo site is well known in the study of Maya art and archaeology due to the presence of notable wall paintings. In this excavation, the team dug into layers of the site that were much deeper than previous discoveries.

“Among the fragments was a little piece of plaster (that) was part of the wall and some black lines,” Stuart said. “When I saw them I said, ‘Oh, well, there you have a Maya calendar record,’ and it was very readable.”

The fragments were discovered using light detection and ranging or LIDAR, a laser technology used for land surveying.

“(LIDAR) has really reshaped Maya archaeology and the way that we understand the Maya and now other parts of ancient Mesoamerica as well,” said Tom Garrison, assistant professor in the department of geography and the environment. “(It can) let us digitally deforest the landscape and see this basically preserved ancient landscape underneath.”

The fragments contain the words “7 Deer,” which is the name of one of the days in the 260-day Maya calendar cycle. Stuart said the 260-day cycle is a fundamental part of Mesoamerican culture that stems from the multiplication of 13 and 20, two sacred numbers for the Maya. The Maya used 20 as the base for their counting system, and the significance of 13 is most likely linked to the amount of lunar months in a year.

“This would now be the oldest example of a Maya date recorded in any kind of medium,” Stuart said. “It’s probably a ceremonial day, it might be related to the days on which the solar year begins; it could be a lot of different things.”

In order to assign dates to the discovered fragments, they were compared to samples of organic material found in excavations through a process known as radiocarbon dating. Researchers measure the amount of carbon-14, a form of carbon that organisms absorb throughout their lifetime, that is still remaining in order to know how old the organic material is. When an organism dies, the carbon-14 keeps decaying.

The team has excavated most of the building where the calendar was found and is continuing to work in the San Bartolo region. Stuart said that the discovery will contribute to increased interest and education about the Maya calendar, which has often been shrouded in superstition.

“This particular way of counting days, in the 260 days system, survived the Spanish invasion and the conquest, and it was maintained very much in secret up to the present day,” Stuart said. “It’s not a revival. It’s actually a survival of the Mesoamerican past; that’s really extraordinary.”