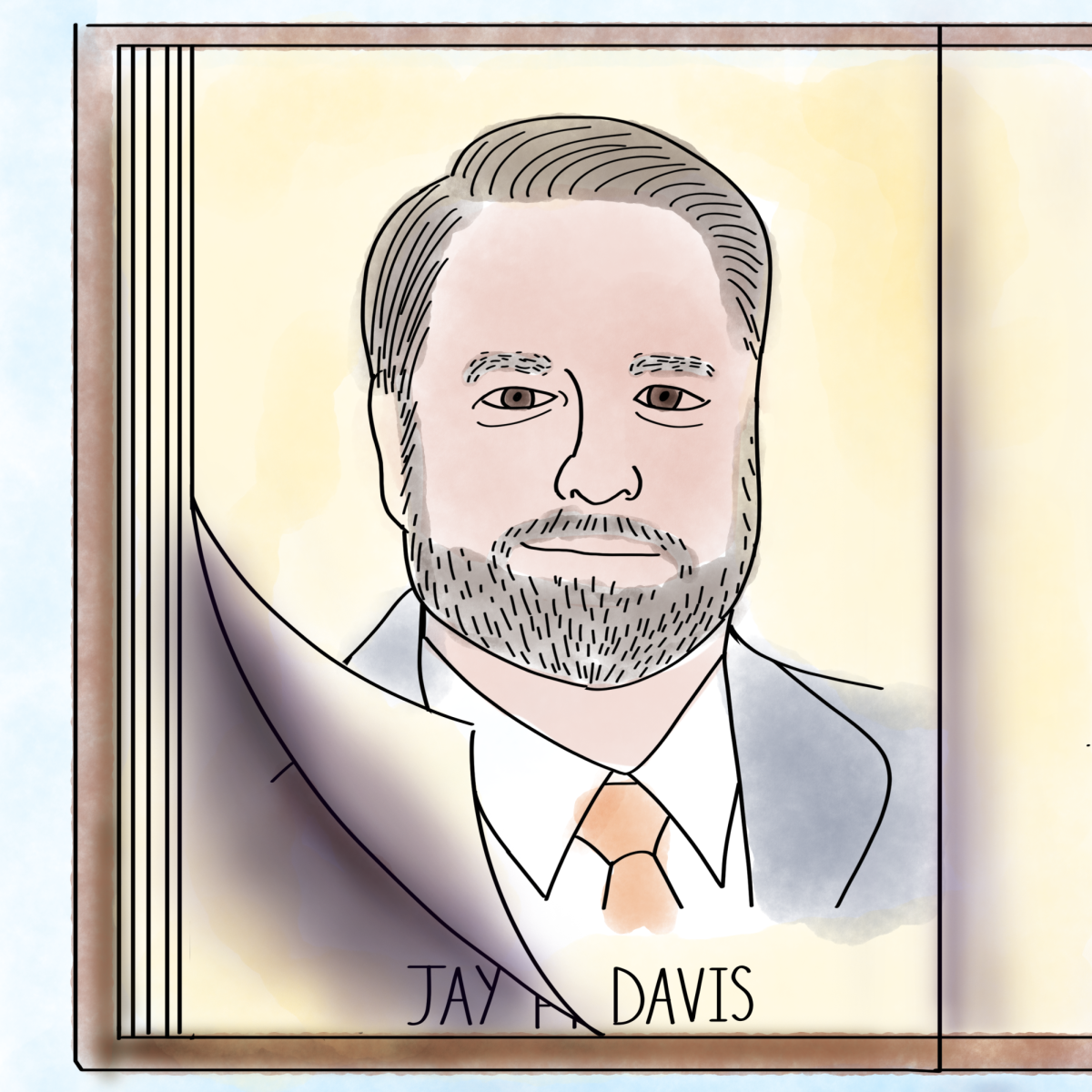

Chapal Bhaduri paints white dots along his forehead, cinches his waistcoat, ties peacock feathers to his wrist and slips on a pair of high heels.

The scene was part of a film clip shown to a group of students and faculty Monday depicting the real Bhaduri, a legendary actor known for his portrayal of female roles on the stage in a time when women did not perform. The Bengali film “Just Another Love Story” does not just present an account of the cross-dresser’s life, but also tells the story of a transgender documentary filmmaker whose bisexual lover is the cinematographer.

The 2010 film is just one of many included in a new genre, referred to as “queer Bengali cinema.” These films, which emerged during the past two decades in Bengal, center on “queer” protagonists and challenge heterosexuality in India, said Shohini Ghosh, a professor at India’s AJK Mass Communication Research Centre. Ghosh spoke to those involved in the UT Hindi Urdu Flagship program, designed for students looking to further their research in Hindi-Urdu languages and culture.

“There is an increasing amount of space devoted to discussions of sex and sexuality in the print and electronic media [in India],” Ghosh said.

The 1990s witnessed a radical restructuring of India’s urban media, globalization and the rapid proliferation of satellite television channels, creating new outlets for questioning sexuality, according to Ghosh.

Ghosh said she is tracing the emergence of queer Bengali cinema in an attempt to retrieve stories nested within the “shadow zones of suggestion.”

“Normally the discussion of queer lives falls through the cracks of history and biography writing,” Ghosh said.

Ghosh said she is using a visual archive to get a sense of what’s happening beyond a topic that remains somewhat socially unacceptable to write about.

“[Ghosh] brings up issues of marginalization and of alienation that have not been addressed in the sort of traditional approach to the field, bringing to light these issues that have sort of been there but not addressed adequately,” said Syed Hyder, associate professor of Asian studies.

In 2003, the Indian government banned a queer film saying it promoted perversion and endangered the institution of marriage. This led to the first public debate of sexuality and took the movement to new heights, Ghosh said.

“The post-liberalized media has a more uninhibited approach to issues of sexuality and queer activism that is saying ‘Let’s make this space and let’s have these debates,’” Ghosh said.

Kamala Visweswaran, associate professor of anthropology and South Asian studies, said Ghosh’s work to archive these films is important not only to the future of Indian attitudes toward an emerging third-gender, but also to assessing prejudices of the past.

“[The visual archive] points to a kind of a horizon,” Visweswaran said. “The visual archives point to a set of possibilities, not only for the future but how we encounter the past.”