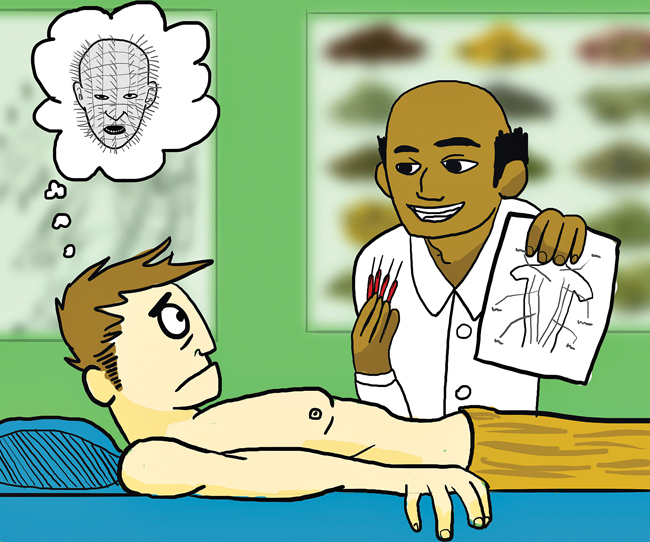

You’re tired all of the time. Or maybe you’re suffering from back pains that, no matter how many doctors you’ve seen, can’t be cured. That must be because you’re stuck in the paradigm of traditional, evidence-based “Western medicine.” Maybe you need something different — something mystical that doesn’t require the kind of proof and testing that ordinary medical procedures do. Maybe you need something like acupuncture.

Acupuncture is a method, supposedly originating in ancient China, where the practitioner uses thin needles to poke various “acupoints” on a patient’s skin to unblock the body’s “qi” (core energy) and treat, well, anything.

Chronic pain? Sure. Cancer? You bet. AIDS? Of course. By reducing anything that can possibly be wrong with you to a mystical, undetectable energy, proponents of acupuncture don’t have to limit the scope of their treatment the way that traditional medical practitioners do.

So, the question really is, does it work?

Good experiments regarding acupuncture are hard to find, mainly because it’s difficult to eliminate a placebo effect: You generally know whether somebody is poking you with needles. Scientists are nothing if not resourceful, however, and have developed several “sham acupuncture” treatments to act as controls. The simplest involves placing needles at non-acupoints on the subject — as long as the patient isn’t familiar with where the needles are supposed to go, then the experiment is single-blinded. A single-blind experiment is one in which information that could bias the results of the experiment is withheld from the test subject.

Another technique involves using needles that create the sensation of a poke without actually penetrating the skin: If the patient can’t see the needles, this should also do the trick.

A fairly recent study using both of these control strategies found no difference between either of them and “real” acupuncture in the treatment of fibromyalgia, a condition characterized by chronic pain.

So acupuncture doesn’t work for fibromyalgia, but couldn’t it still work for, say, allergies? Or back pain? Do we really need to test it for every possible condition to find out that it doesn’t work?

No. The burden of proof, as always, is on the proponents and, anecdotes aside, this burden hasn’t been met — throughout the acupuncture literature, the better the study is, the smaller the effect becomes. Fortunately, neither the absence of evidence nor evidence of absence has stopped believers from taking the ideas of acupuncture into even more ridiculous directions.

For instance, a practitioner can work sans needles. According to the Needleless Acupuncture unit’s instructions — which feature full-color clip art images of a tiger and a dragon, like most manuals for medical equipment — the device penetrates the skin using magnets rather than actual needles. Of particular interest are the two separate magnets sold with the unit: a north pole and a south pole. If this is true, then the manufacturers have discovered the mythic monopole, which has eluded physicists for well over 100 years, and deserve a Nobel Prize.

But they should probably stay out of medicine since studies have repeatedly shown that magnetic therapy doesn’t work, either.

Also, unlike most medicines, which are tested on animals for safety before moving on to human trials, acupuncture went the other way around. Pet acupuncture isn’t nearly as uncommon as you might think (or hope). A Yelp search in Austin, for instance, finds no fewer than 12 results for veterinarians who offer acupuncture treatments

for dogs.

A systematic review has catalogued the current research looking at acupuncture’s effect on not only dogs, but horses, pigs, cattle and sheep as well. The results are, unsurprisingly, as unremarkable as they have been for human studies.

Medical testing is a difficult, lengthy, risky and extremely expensive process, but it’s necessary in order to find treatments that work beyond the illusion of one’s own flawed perceptions. Magic talk about life energies and mystical treatments that offer the possibility of curing what traditional medicine can’t may sound reassuring, but ultimately, no reliable experiment has provided any evidence to back up those claims — and many have refuted them.

Real treatments come with real risks and real side effects, sometimes as bad or worse than the disease itself, but, unfortunately, as flawed as these cures may be, they’re the best we have.