Five years after a thorough, University-backed report, a statistically significant pay gap between male and female full professors has shrunk, but the gap has not disappeared entirely. Female professors who disclose pregnancies to department chairs are given the choice to opt into, rather than out of, teaching classes during the semester when they are pregnant. Today, there are 16 lactation rooms on campus that did not exist five years ago.

But according to Gretchen Ritter, vice provost for undergraduate education and faculty governance and government professor, there is still much that needs to be done to increase gender equity.

“We need to remain committed to this work,” Ritter said. “Representation issues at the full professor level and at the senior leadership level are still important issues — there’s a lot of work that remains to be done.”

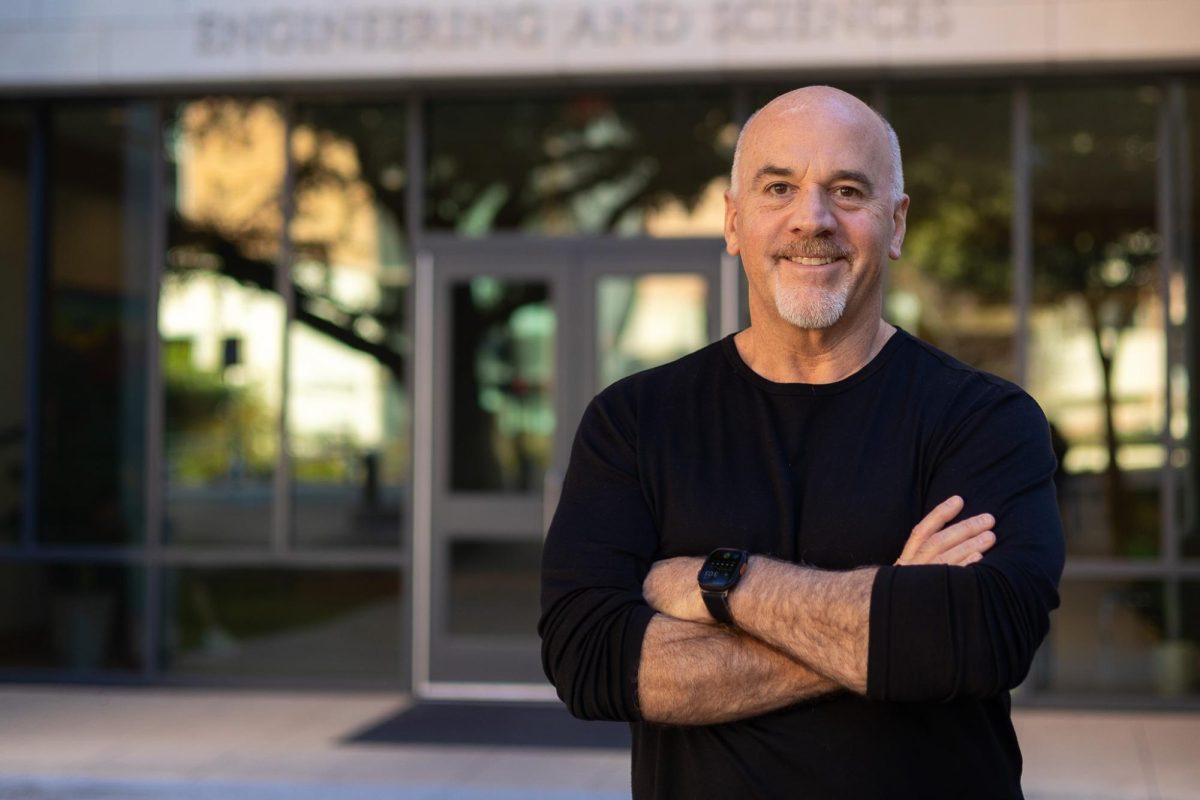

In 2008, Ritter and J. Strother Moore, an electrical and computer engineering, computer science and math professor, co-wrote the final report of a Gender Equity Task Force commissioned by the then-newly hired provost, Steven Leslie. Leslie asked the 22-member task force to focus on all that “remains to be done in order to make UT-Austin an inviting and productive place for women faculty members in all areas.”

The report identified nine categories of gender equity issues on campus, ranging from a promotion and attrition gap for advancing female faculty to a lack of awareness of family-friendly policies already available on campus. But today, the progress the University has made proves difficult to gauge.

The University accomplished certain objectives, including creating a dual-career assistance office, while other goals, including reducing the wage gap, have faced roadblocks because of financial shortfalls stemming from an economic downturn.

Hillary Hart, a civil, architectural and environmental engineering lecturer, served on the 2008 task force and has held a position on the Faculty Women’s Organization steering committee for 20 years. Hart cited the report’s findings on campus climate as an important part of understanding what it is like to be a female faculty member at the University but said no updated information has been gathered.

“When I looked at the original report, that was the saddest part to read,” Hart said. “The women faculty, especially the full professors, not feeling that they were valued by their peers, not feeling that they were seen as doing good work, or worthwhile work. The women didn’t feel like they were making a difference.”

The report also found that on average, male full professors’ salaries were $9,028 higher than their female counterparts. University administrators attempted to address this through a series of targeted salary increases in the 2009-2010 school year, but state budget cuts slowed momentum.

“The salary differential has not been eliminated, but it’s been addressed,” Hart said. “The administration made big strides in 2009-2010, but then all hell broke loose with the budget cuts. So they’re still sort of working on that.”

Ritter emphasized her belief that gender equity is directly tied to the competitiveness of the University.

“In academia you’re in the talent business first and foremost and you want to find the most talented teachers and researchers you can,” Ritter said. “To do that, you first need the broadest possible pool of talent — and if you’re somehow limiting your access to half the pool, you put yourself at a disadvantage.”

On the whole, Ritter said she would give the University’s efforts toward gender equity over the past five years a B grade.

“I think we probably deserve a B,” Ritter said. “By the way, I’m a tough grader, so a B’s not bad. I think it’s unfortunate that the timing turned out to be such that we’ve had so many things we’ve had to be focused on and address, but I am encouraged and hopeful about some of the plans I have heard.”