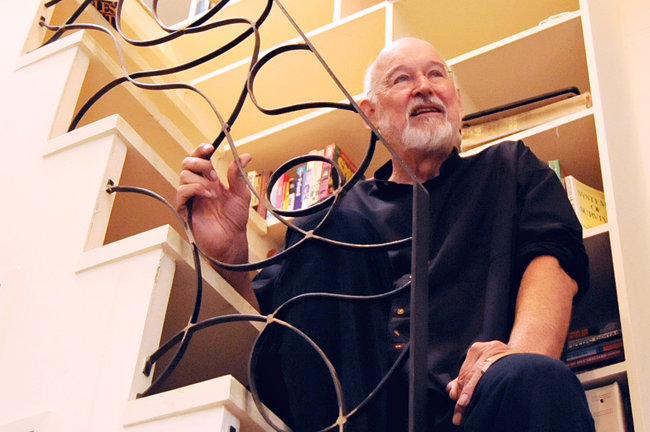

Austin focal points, such as Barton Springs, Livestrong and Dell Computer, would not be what they are today without Lee Walker’s leadership.

Walker, a senior research fellow at UT, helped lead civic projects such as Save Our Springs in the early 1990s and a project in the early 2000s to prevent the state from constructing a conventional strip mall instead of developing what is now Triangle Park. Walker also is a co-founder of Livestrong and was the president of Dell Computer for four years.

“Those kinds of quixotic ventures really appeal to me,” Walker said. “I love things that have no chance.”

Though Walker said he valued his work with the diverse array of projects, he also views his experiences as a useful foundation from which he can teach.

Walker will teach two classes in the spring semester: Pathways to Civic Engagement, a class for Plan II students, and Civic Viewpoints, which will be open to all students.

“[The] class I teach is at the intersection of entrepreneurship and justice and place,” Walker said. “It’s just important to get out into the field and see what’s

going on.”

Walker’s students go on field trips to meet members of the Austin community who are working to improve citizens’ lives.

“I think that’s the beautiful part of civic engagement, that over time you have the opportunity to develop friendships and connections with just extraordinary souls,” Walker said. “It’s a wonderful thing.”

Erin Larson, business honors and Plan II junior, said Walker’s class taught her to challenge the status quo and break the cycles of problems.

“The movers and shakers of the Austin community … not only went about to solve the existing issues or challenges they saw within their communities, but they went upstream, to the very origin of the issues, to attempt to eliminate the problem instead of merely treating the symptoms,” Larson said.

Each year, Walker spends the fall reinventing the class with his teaching assistant. Holland Finley, business honors and Plan II senior, was Walker’s teaching assistant for last spring’s class.

“I think the overarching theme of his mentorship has been to give me and others the confidence that no matter what pathway my life takes, I am able to transform the world for the better,” Finley said.

Walker grew up in Three Rivers, a town in Southern Texas, and as a student there he visited Austin for athletic and academic contests.

“[Austin] was the epicenter of our universe,” Walker said. “We’d come here for the state finals or whatever, and go, ‘Someday, somehow, some way, I will live here because it’s the greatest place on earth.’ There was nothing else like it.”

Upon his 1963 graduation from Texas A&M University, where he studied physics on a basketball scholarship, he received a doctoral fellowship in nuclear physics from NASA. Two years into Walker’s doctoral program, he visited NASA and realized he didn’t want to continue researching cosmic rays.

“I saw what I would be doing and what my colleagues were doing and came out thinking, ‘That is incredibly boring,’” Walker said.

On a whim, Walker decided to apply to Harvard Business School. Though he did not have a business background, or any specific interest in business, Walker said several people encouraged him to give the school a shot.

Walker said he felt terrified and unprepared when he finally arrived at Harvard.

“My classmates just seemed so sophisticated and worldly and knew a lot about business already,” Walker said. “You really weren’t supposed to go there unless you knew business.”

It was at his first job out of business school that Walker was first introduced to entrepreneurship. While working at Union Carbide, a company that works in chemicals and polymers, Walker met a man who identified as an entrepreneur.

“He started talking about entrepreneurship … and I think I just cocked my head, like, ‘What a funny word,’” Walker said.

Walker said the trajectory of his career accelerated after he quit his position at Union Carbide. He said he quit

because he felt the company was prejudiced against one of his Jewish coworkers. In response, the company offered him a chief financial officer position at a company in which they had minority ownership.

“Carbide said, ‘First of all, you won’t be working for us,’” Walker said. “‘You’ll be working for this little company.’ That moral choice probably accelerated my career by 10 years because [chief financial officer] is not a job you get when you’re out of school.”

Walker has four children and two grandchildren and spends each summer in Italy with family, but said he has no plans to retire.

“I’m 72 now, and I fully intend to keep [teaching],” Walker said. “I will, when I’m 100, re-evaluate, but I think I would like to continue even then.”