There’s an old joke about an engineer, a physicist and a philosopher who end up in Scotland and see a black sheep.

“Sheep here are black,” says the engineer.

“Some sheep here are black,” says the physicist.

“One sheep here is black,” says the philosopher. “Or at least one side is, anyway.”

That’s the issue facing psychology at the moment: We’re assuming all sheep are black based on a limited sample size. The overwhelming majority of experiments — about 98 percent — focus on subjects from Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic societies and, in many cases, the conclusions assume the results represent all of humanity. The problem is that these societies only represent about 12 percent of the world’s population.

And many subjects differ from Western societies in surprising ways. Maybe members of non-industrialized societies can’t solve advanced differential equations, but they can probably count their fingers and toes, right? Not always. The Piraha people of Brazil can’t count to 10. What makes this fact even more confusing is that their word for the number “one” often refers to “a small amount” compared to their other counting word, which loosely translates to “a large amount.” Even small numbers prove difficult for the Piraha subjects: When forced to distinguish between three and four, they only succeed about half of the time.

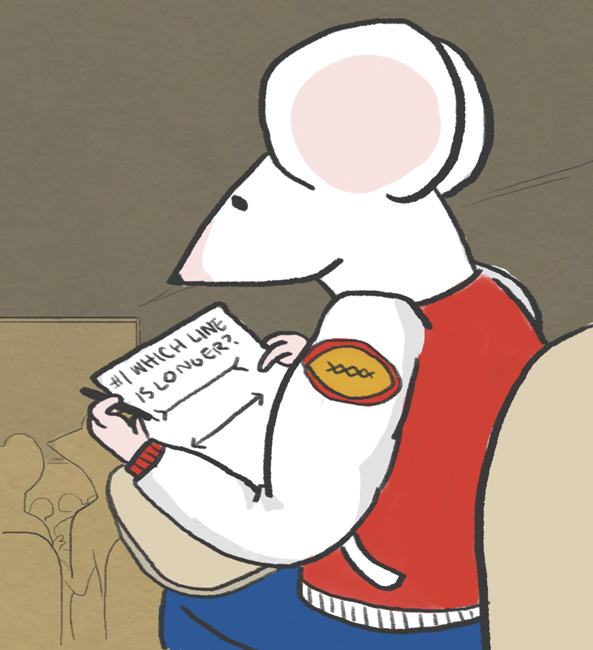

There’s also the Muller-Lyer illusion, where two identical lines, placed next to each other, appear to be different lengths because of the opposite-facing arrows on their ends. The illusion is so strong that, short of measuring the two lines with a ruler, most Western subjects refuse to believe that the lines are equal lengths.

But for certain groups culturally separate from us, there is no illusion at all. They see the lines as the same exact length. For those cultures where there is an effect, none experience it as strongly as Americans do.

Why? Researchers think that it may have to do with the straight lines and sharp corners that surround us growing up, but that doesn’t necessarily sit well, especially since the illusion is even more pronounced in children than in adults. Though Europeans grow up in similar environments and experience the same effect, it’s not as strong as it is in Americans.

Which shows that, even among Western countries, there’s plenty of variation.

For instance, in the Ultimatum game — a staple for psychological studies looking at how humans cooperate — one player chooses how much money to offer another one. The second player can either accept the offer, in which case both players keep the money, or decline it, in which case neither player gets anything. The less you offer, the more you can keep, but if you’re greedy and the other player is resentful, you risk losing everything.

In the U.S., the smartest bet is about 50 cents. But in a number of different cultures, the best bet is to only offer a dime because other people will more or less accept whatever they are offered. And some places, such as China and Russia, as well as Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands to a lesser effect, show examples of subjects refusing offers that are too high — something that never happens in the U.S.

None of this is to say that there aren’t human universals. All human cultures have language, so far as we can tell, as well as concepts of right and wrong, religious beliefs and gender roles. But it’s important to keep in mind that different cultures and environments produce different kinds of people.

Evolution acts on every part of us, including our brains, and it’d be surprising to find that natural selection hasn’t molded our psychology as it has the rest of our bodies. Before making sweeping generalizations about the entire human race, we’d better test more than just the small sample that happens to be easiest to study.