The Engineering Sciences Building — a 50-year-old facility that houses the University’s electrical engineering program — has run its life course.

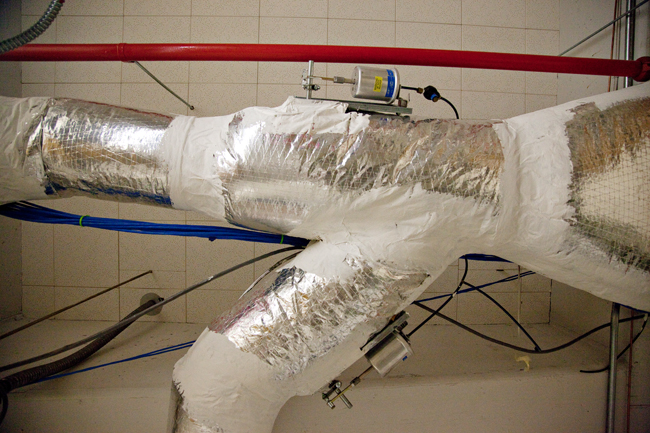

Ceilings open up to exposed pipes and wires, electrical fans cool computer servers in a hot building and a study room is closed every summer because it does not have air conditioning. In this industrial building, professors teach students 21st-century engineering without modern labs. But after several years of fundraising and planning, the Cockrell School of Engineering is set to begin constructing the $310 million Engineering Education and Research Center to replace the Engineering Sciences Building. With 430,000 square feet of classrooms, labs and offices, the new building will become the second biggest academic building behind Welch Hall.

Engineering dean Greg Fenves said students will learn modern engineering through a hands-on approach in the new building, which will create more spaces for collaborative research. He said this is a necessity in engineering education that the college has struggled to meet with existing facilities.

“There are dramatic changes taking place in how we educate engineers. It’s moving from the classroom to the laboratory,” said Fenves, who will leave his position as dean and become the University’s provost in October. “We are severely limited by our facilities because they were never designed to do this. They were designed to teach students sitting in chairs that are bolted to the floor with a professor at the blackboard at the front.”

The Engineering Sciences Building was built in 1963 for applied physics research. In the 50 years since, the building has become home to electrical engineering students — the Cockrell School of Engineering’s largest undergraduate program.

Perry Durkee, the building manager who has worked in the Engineering Sciences Building for 32 years, said it has constantly been patched up with construction and renovation projects.

“It’s been in a constant state of change. The building was built for one purpose, and we have used it for another purpose,” Durkee said. “We’ve spent a lot of time and a lot of trouble trying to make it look more modern. But it’s a lost cause now.”

Fenves said the building was constructed in an age when vacuum tubes, which were retired decades ago, were used in radios, and electronic integrated circuits were much simpler with seven components rather than billions of components that make them up today.

The lack of modern labs has hurt the engineering school’s ability to recruit top faculty, Durkee said.

“It’s impossible to say how many faculty recruits we’ve lost when they’ve come to this building to see it,” Durkee said.

Even though most of UT’s engineering buildings are older than those of other universities, including Texas A&M University and the University of California-Berkeley, the University’s engineering program has remained competitively ranked.

“We have primarily been doing well because we’ve been so successful in hiring great faculty,” Fenves said. “But that is getting tougher to do because of our facilities. We will not be able to continue without the new facilities.”

Meanwhile, Durkee said the building has several other issues, including an air conditioning system that is no longer sufficient to support the number of people who occupy the building.

Earlier this summer, smoke from the air conditioning system caused the fire alarms to go off and led to a building evacuation. Meanwhile at the Texas Capitol, lawmakers failed to pass a bill that would have provided $2.7 billion in state funding for higher education construction projects, including the proposed Engineering Education and Research Center. Following the failed bill, the UT System Board of Regents approved up to $150 million in available funds the University could borrow to supplement fundraising efforts to finance the new building earlier this month.

The Engineering Education and Research Center is the first of nine construction projects in the school’s “Master Facility Plan,” which aims to construct six new facilities and renovate three outdated engineering buildings on campus.

“The plan is very logical, very well laid out and visionary. But it was very clear that the first step had to be a building in the center of our engineering precinct,” Fenves said. “It had to replace [the Engineering Sciences Building].”

Unlike the current facilities, Fenves said the new building will allow for interdisciplinary research and entrepreneurial efforts, and its facilities will be adaptable to changes in engineering education.

“We don’t know exactly what kind of research is going to be done in the labs in the next 10, 20 or 50 years,” Fenves said. “It’s going to change. We’ve never had facilities like that before.”

Associate engineering dean John Ekerdt said the University is still making final decisions on a timeline for building the new facilities, but construction on the building could begin late in 2014 or early 2015. The building is set to open in 2018.

While the building is being constructed, Fenves said the college will disperse classes, labs and faculty to other buildings. He said undergraduate instructional labs will move to Ernest Cockrell Jr. Hall, and many faculty and graduate students will move to an administrative building on the corner of 17th and Guadalupe Streets.

“It’s important that everybody understand that there will be disruption, and we’re going to try to minimize it, but the benefit of that destruction is moving back to an incredible, state-of-the-art facility,” Fenves said.

slideshow courtesy of the Cockrell School of Engineering