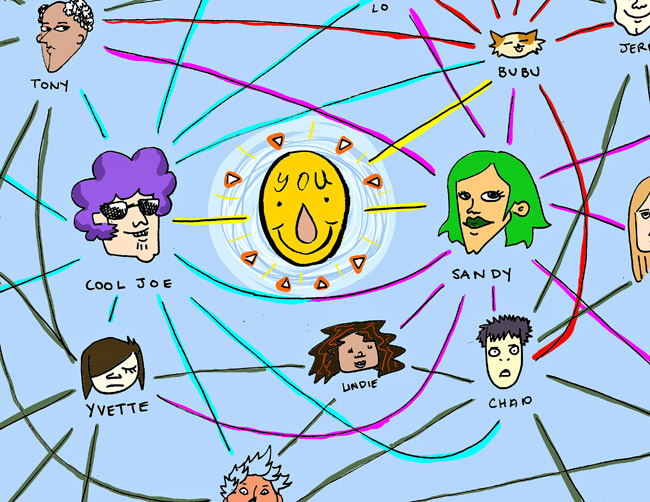

Comparing yourself to others is a recipe for low self-esteem. There’s an illusion that comes from comparing ourselves to those around us and it’s not just psychological: It’s mathematical.

In 1991, sociologist Scott Feld published a paper with an unexpected result: On average, people don’t have as many friends as their friends do. The conclusion came from looking at data collected 30 years prior in a study looking at the friendships of teenagers from 12 different high schools, where each was asked to make a list of their friends. When two people named each other, it was considered a mutual friendship. These mutual relationships account for the reason people have fewer friends than their friends have.

At first, Feld’s result seems as preposterous as the concept perpetual motion in physics. There are a finite amount of people in the world and with the way averages work, everything should balance out.

The result holds and applies in other situations. Ever wonder why everyone at the gym looks like the Hulk while you struggle to look like Bruce Banner?

Same reason.

The idea is that the measured quality is inherently unbalanced. Not only does Joanne the Popular have 20 friends, but her numbers are counted in 20 different friend circles. Compare that to Joe the Nerd, whose three friends only bring down the average in three friend circles. Another way of looking at it is you’re more likely to befriend people with many friends than those with few. More recent results using Facebook have found that the result applies to cyber-friends as well.

Similarly, while many students visit Gregory Gym, the ones who you are most likely to see while you’re pumping iron are the ones who spend the most time there — that is to say, those who can practically bench press a Volkswagen.

In short, this is another conclusion that seems to fall under the category of “averages can be misleading.” But unlike mean incomes or questions about averages on the SAT, the “Friend Paradox” may actually have some practical use.

The biggest potential application is in preventing the spread of disease. Suppose, for instance, that a major pandemic sweeps the nation and there’s a vaccine produced in limited supply. To prevent the disease from spreading, it makes sense to give the vaccine to those who are most connected to other people.

It’s for this reason, not only should you get a flu shot every year, but you should encourage your friends, co-workers and family to do so as well. The production of the yearly vaccination requires some guesswork, but according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the risk reduction may only be about 60 percent.

But if more people get the shot, then the virus can’t spread as easily. When you vaccinate yourself, you’re not just protecting yourself, you’re protecting others as well.

The science behind social networks also shows how interconnected we are. The term “Six Degrees of Separation” suggests that any given two people are only six nodes apart from each other, and experimental results are consistent with these conclusions. In a study, researchers gave participants the job of forwarding an email to someone who would forward that email to someone else with the intent of eventually reaching a target individual. The median result was between five and seven degrees of separation, though it’s unlikely the emails took the quickest path from the initial person to his or her target and the number is almost certainly much smaller for two people who are geographically close to

each other.

What does this mean? Nothing surprising, perhaps. But the next time you’re in a position to offer up a small bit of kindness to a stranger, remember they’re almost certainly a second or third-degree friend.