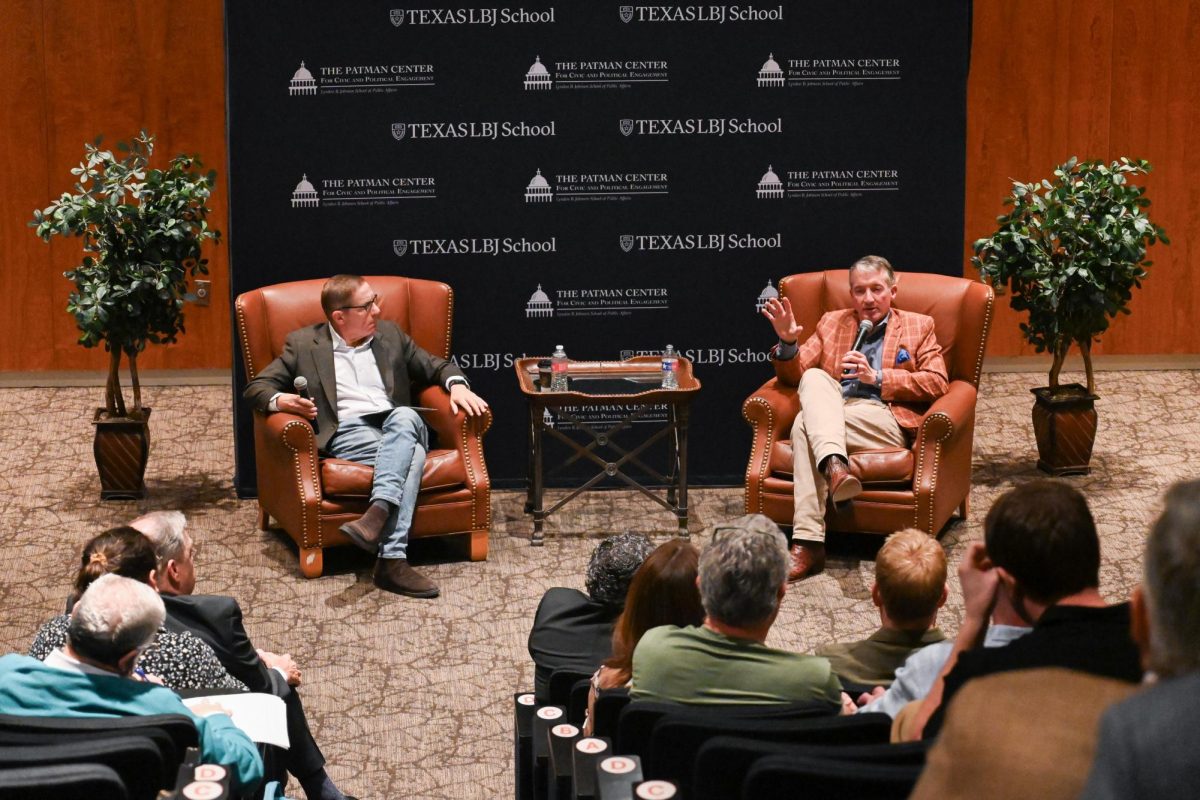

In a talk hosted by the School of Law on Tuesday, attorney Vincent Warren spoke about leading a “stop-and-frisk” case, and the need to reform laws that allow racial profiling. Warren — the attorney and executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights, an organization focused on advancing and defending civil rights — represented the plaintiffs in Floyd v. City of New York, a 2013 court case involving New York City’s “stop-and-frisk” law.

The law, which is currently under reform, allows police officers to stop and search people on the city’s streets in an effort to prevent crime and other violent behaviors. The Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable search and seizure, prevents officers from searching someone without a probable cause, but Warren said police were abusing the law and disproportionately searching minority groups, which led him to suspect racial profiling.

“From looking at police logs, we found that African-Americans and Latinos were stopped 87 percent of the time, but they only make up 23 percent of the New York City population,” Warren said.

According to Warren, litigants found evidence that specifically showed police used racial profiling to stop people.

“[Police captains] would tell the officers, ‘You gotta stop the right people,’” Warren said. “There was an order [from the precinct captain] to stop every black kid they saw with a backpack coming out of the train station at 3:00 in the afternoon.”

Helen Gaebler, senior research attorney at the William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law, said she found the effects of the stop-and-frisk law on New York interesting.

“There was an increase in clients picked up for trespassing,” Gaebler said. “The police could stop you for almost anything: for being in a high-crime neighborhood or just [by] fitting a certain description.”

Warren said the stop-and-frisk law was designed to stop crime before it started, but it often made police jump to conclusions based on race, sometimes leading to disastrous results.

“In 1999, there was a black kid named Amadou Diallo who was stopped by the NYPD,” Warren said. “According to the police log, he made ‘furtive movements,’ so they thought he had a gun. He got shot 41 times just because he was pulling out his wallet for [his] ID.”

Warren went to court against the NYPD to try and resolve the issue, and although the case went back to appeals court several times, he eventually succeeded in proving the NYPD was unconstitutionally stopping and frisking people.

The NYPD expects to reform its stop-and-frisk practices within three years.

“It is an epic fail when you’re [frisking] people at a larger percent than they occur in the population, when you’re policing neighborhoods using racialized stereotypes and assumptions, and [when you’re] not getting the job done,” Warren said.

According to Warren, one important aspect of the Floyd case was how it helped promote social justice.

“Usually, a court case by itself is not enough to actually change people’s behavior,” Warren said. “But, with this case, the genesis came from wanting to evoke social change.”

Law student Kallie Dale-Ramos said she thought the case was important for its ability to make reforms.

“I’m interested in public-interest cases, so I thought it was neat how the case actually had an impact on public policy,” Dale-Ramos said.