Feb. 12 of every year marks Darwin Day, a holiday celebrating the anniversary of the birth of the famous scientist who offered what is, arguably, the single greatest theory of modern times. Natural selection provides an explanation for how order can come from disorder and how an unthinking process can, given time, give rise to a thinking creature who can uncover said process and give it a name.

But natural selection works in strange ways, and “survival of the fittest” doesn’t explain how every trait evolved.

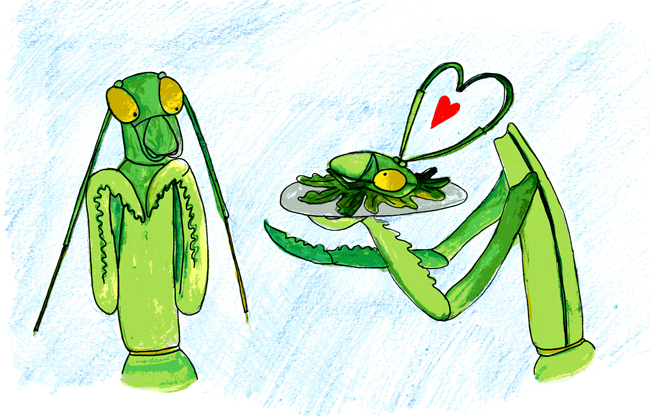

Take the praying mantis, for whom the term “battle of the sexes” takes on new meaning. In a Science magazine article from 1886, author L. O. Howard describes his observations of a male mantis attempting to court a female: “She first bit off his left front tarsus and consumed the tibia and femur. Next she gnawed out his left eye. At this, the male seemed to realize his proximity to one of the opposite sex and began to make vain endeavors to mate.”

By contrast, human dating sounds downright pleasant.

Female mantises do occasionally eat their mates. This has been observed in the lab as well as in the wild. But it’s unlikely that there’s any evolutionary advantage to the male allowing himself to being eaten.

Like most insects and arachnids, female mantises are larger than their male counterparts and can easily overpower them. Since this father-to-be won’t stick around to help raise the kids — don’t judge, neither will the mother — the female might as well get some use out of last night’s mistake by eating him. It’s not that she can’t tell the difference between mantises and other insects; it’s that she doesn’t care.

Given the opportunity, she will even eat the male before he has a chance to mate with her. It’s for this reason that the male mantis is equipped with two abilities to help him in his efforts.

The first is his ninja-like stealth. Not only will he creep around, avoiding detection, but, if spotted, he will stand perfectly still, in some cases with a leg frozen in midair. Mantis vision is based on movement, so, by keeping still, the male effectively becomes invisible to the predatory female.

But, what if she does catch him? He’s got another ace up his sleeve.

Instead of telling bodies when to mate, mantis brains tell the bodies when not to by actively inhibiting sexual reflexes. When the female takes a bite out of the male’s head, the remaining body does everything it can, perpetually gyrating, in an effort to mate with whatever is in the vicinity — be it female mantis or an experimenter’s finger. These movements will continue even after the female finishes his head and moves on to his abdomen. As Howard noted, “nothing but his wings remained.”

The competition of natural selection occurs between individuals and not between species. Though there are genuine examples of altruism in specific cases — humans being the prime example — sacrificing one’s life is rare, indeed. The beauty of nature arises from individuals looking out for themselves, trying to spread their genes and theirs alone.

Though computer models have come up with situations where it may be beneficial for the males to be eaten, it’s unlikely they apply often in real life, if at all. This is almost certainly true in the mantis, where observations record the male doing everything in his power to actively avoid becoming the female’s next meal.

So, the next time a hot date orders the lobster after having offered to pick up the check, remember that it could be a whole lot worse: He could have ordered you.