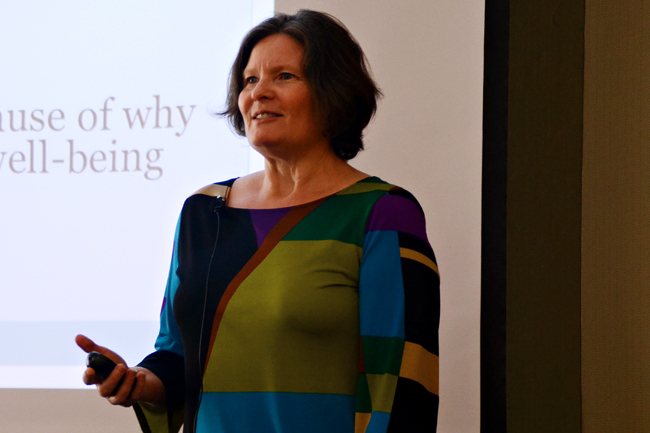

Being a parent in the U.S. doesn’t make you any happier in life, according to sociology professor Jennifer Glass.

Glass’s research shows that parents in the U.S. are unhappier than non-parents by the largest margin almost anywhere in the world.

In a talk on campus Friday, Glass spoke about why some parents are happier than others, and how parenthood influences happiness in different countries around the world.

Glass said there is a widespread cultural belief that parenthood improves adult wealth and happiness.

“If you go ask parents, they’ll tell you, ‘Being a parent is great. I love my kids. It’s best thing I’ve ever done,’” said Glass. “Then you go to the empirical data, and find that all types of parenthood have negative effects on happiness and mental health.”

Glass said one reason for this difference might be that parents derive fewer emotional benefits from parenting than they do from their other adult social roles.

“Employment and marriage provide you with money and social status,” Glass said. “Parenthood doesn’t provide you with either of those and exposes you to more stress, which either cancels out or exceeds the emotional rewards of having children.”

Glass used social surveys to determine levels of self-reported happiness for parents and non-parents around the world. After comparing these levels to the amount of institutional support each country provides for parents, she found the gap in happiness between parents and non-parents varied in different countries, with the two biggest factors contributing to parental happiness being the cost of child care and amount of vacation or sick leave provided to employees.

Sociology professor Bob Hummer said he agreed with Glass’s hypothesis.

“When kids are young, [parenting] is stressful and difficult, and the U.S. doesn’t provide a lot of support [for parents],” Hummer said. “My kids are 21 and 16, and as kids get older, it’s a different kind of stress, but it’s still there.”

Glass said countries such as Norway and Denmark have higher levels of support for parents than the U.S. through benefits like longer maternity leave or cheaper child care.

“Things are terrible in the U.S. relative to other countries,” Glass said. “The gap would be lessened if we had institutional support intended to reduce parental stress.”

Sociology graduate student Amanda Bosky said Glass’s research wouldn’t affect her personally.

“I don’t think it would have any effect on my personal decision about whether or not to have children,” Bosky said. “It does make me wish I lived in countries like Norway, though.”