It is rarely quiet for Nicole Thompson Beavers, but she savors silence in her office when she can. Leaning back in her chair, she calmly gazed into the coffee between her hands. Sighing, she raised the cup to her — “BLAM!”

Then she set the cup down on the — “BLAM!”

Swiveling to her computer, Thompson Beavers, a graduate program coordinator, pushed the disturbance from the weight room above her office out of her consciousness, a practice that took weeks to master.

The repetitious pounding continued above in the Bellmont weight room facility in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, where UT students and faculty are permitted to exercise in a historic environment.

Fifty years ago, Bellmont contained the training facility for the Longhorn football team. But if Thompson Beavers taught all those decades ago, she would never have had an issue with the thuds of heavy iron. Before the 1970s, lifting in football was discouraged — even banned. Now, most colleges have a strength and conditioning program with facilities built specifically to advance players’ strength.

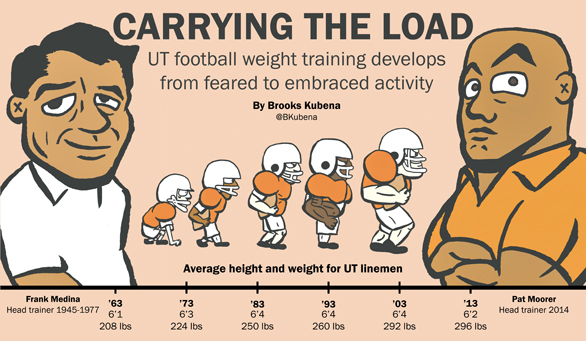

Illustration by Albert Lee / Daily Texan Staff

Part of the history behind that idea lies roughly 100 yards north of the Bellmont facility in the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports, built in 2008 by directors Terry and Jan Todd. At the start of the 2013 football season, Terry Todd felt he had to do something to honor the 50th anniversary of the 1963 championship team and coach Darrell Royal, who died Nov. 7, 2012.

Todd designated a section of the exhibit hall for a large banner of the ’63 team photo to drape down in the main hall and for pictures and items from the life of Royal to be arranged on the walls nearest to the entrance.

While a tribute to a former football coach doesn’t raise any questions, Todd — a UT tennis player in the late ‘50s — knows weight training was looked down upon at Texas until Royal changed that perception.

“It had a terrible reputation that it would stiffen you and slow you down,” Todd said.

Todd tested the theory during the summer after his senior year of high school.

“I played tennis and never did calisthenics or any other exercise, so my right arm was like a crawfish that lost one of its claws and it was just half-grown back,” Todd said. “I did curls, presses and stuff, and I could feel that it was working.”

Todd gained 30 pounds that summer and continued training during his college career, setting him at odds with head coach Wilmer Allison — the co-namesake of the Penick-Allison Tennis Center, where the Longhorns currently play. At one point, Allison threatened to reduce Todd’s scholarship to a half-scholarship.

Todd quit the team his junior year, focusing on a weight lifting course instead.

Strengthening to 270 pounds in 1960, Todd gained a reputation as the strong man on campus and word of his strength even reached Royal.

Royal’s 1960 team finished at 7-3-1 and in early 1961, Todd was unexpectedly called to Royal’s office.

Royal explained that he had heard of Todd from a few of his players and knew of his dispute with coach Wilmer.

But then Royal asked a question that he wanted to keep quiet at the time.

Todd recalled Royal saying, “I want to know more about it because I keep hearing a few other schools are starting to do it. So explain this to me: Why do people believe that [weight lifting is] bad for you?”

Royal grew up in a time where it was believed weight lifting was detrimental and could make you so tight you would be unable to brush your teeth.

But Todd explained how weight training helped him in his athletic career and cited how LSU had implemented a weight training program and won the national championship in 1958.

But according to Todd, Royal could not start a similar program at UT because head trainer Frank Medina would never allow it. Royal couldn’t force the issue either, if he insisted the players lift and injuries resulted or they had a poor season, Royal could lose his job.

Texas won three national championships in the ’60s, but despite the success, Royal’s fear kept the Longhorns from heavy training until the 1970s.

“The only weights that [Medina] ever had us using was when we’d hold them in our hands and do sit-ups and stuff like that,” said Leslie Derrick Jr., a member of the 1963 national championship team. “I don’t know if coach Royal was really excited about [weight lifting] or anything … I don’t think Diron Talbert ever worked out with a weight in his life.”

Although the Bellmont weight facility has been updated since housing the Longhorn football team, its faded floors and walls provide a museum-like look at years past. In the 1960s, the space had much less equipment than it holds today. Photo by Jonathan Garza / Daily Texan Staff

Talbert, a 6-foot-5-inch defensive lineman at Texas from ’63-’66, played in the NFL for 14 seasons. Before he left Texas, the coaches set him up to meet with Todd, who had established himself as a national champion lifter, to test Talbert’s strength. The coaching staff realized for sustained success after college, Talbert would have to “put a little meat” on his bones, according to Todd.

Todd wanted to first test him in the bench press and placed 135 pounds on the bar. Talbert only pressed two reps.

“I thought, ‘My goodness,’” Todd said. “He must just be such a gifted player, so agile and quick and so aggressive. How could you be that weak and be able to be really dominant on the line?”

Heavy weight training was not fully integrated into football weight rooms around the country until the ’70s, reaching a new generation of athletes such as former UT strength and conditioning coach and president of the College Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association, Jeff Madden.

Madden grew up in Cleveland, Ohio during the ’70s, when athletes were beginning to eliminate the weight lifting barriers of fear in sports.

“We had to break that phobia in my household, first of all, so that I could start training,” Madden said.

Throughout his 30 years of coaching, Madden helped lead strength and conditioning into the modern era. He’s watched as football players have grown substantially as the years have progressed. The weight listings of Texas players tell this story.

On the 1963 Longhorns football team, the average weight of a defensive and offensive lineman was 208 pounds. On the 2013 team, 296 pounds.

“You’ve got to be bigger, faster and stronger because everybody else is bigger, faster and stronger,” Madden said.

Weight room facilities have increased in size and supply in the recent years. New workouts have also developed such as tire lifting, where an athlete flips a tire from one end of the floor to the other. Photo courtesy of Texas Athletics

Recently graduated defensive end Jackson Jeffcoat said Talbert’s example of the past makes the difference clear.

“That’s the difference, we lift weights a lot more and lift a heavier weight style,” Jeffcoat said. “Like me, I had two [pectoral] injuries and I was still able to lift a bench 18 times. When my dad came out [in 1983], he benched 225 pounds 18 times.”

Typical lifting workouts for Jeffcoat consisted of either bench press or incline bench press, alternating with dumbbell bench or leg workouts like squats. Other days, there are “power” lifting workouts for the lower body such as leg cleans, where a standing Jeffcoat would lift a weighted barbell off the ground.

None of these workouts were a part of football training 50 years ago. But Jeffcoat said he understands the fears coach Royal and others had about losing flexibility.

“Shoot, I see where [Royal’s] coming from because I know some guys that lift so much but they don’t stretch, and that’s why they get so tight,” Jeffcoat said. “But if you’re stretching and you’re lifting, you’re going to be able to do all your normal functional things.”

Although there has been innovation in weight training, new problems have surfaced. Both Madden and Jeffcoat said athletes have to be careful not to over train muscles; too much focus designated on a specific muscle could result in physical stress and injury. As Jeffcoat enters the NFL Draft, he progresses into the future of football and weight lifting and said he does not know what changes to expect.

“Who knows?” Jeffcoat said. “Fifty years from now I might look back and see that they’re doing something different and making people bigger but there’s not many injuries … But every year you see they come out with something new, so who knows what they’ll come up with next.”

Much has changed since a Pro Bowl defensive lineman could only bench 135 pounds twice. And as innovations continue, strength and conditioning coaches, football players and coordinator Thompson Beavers, will have to adapt.