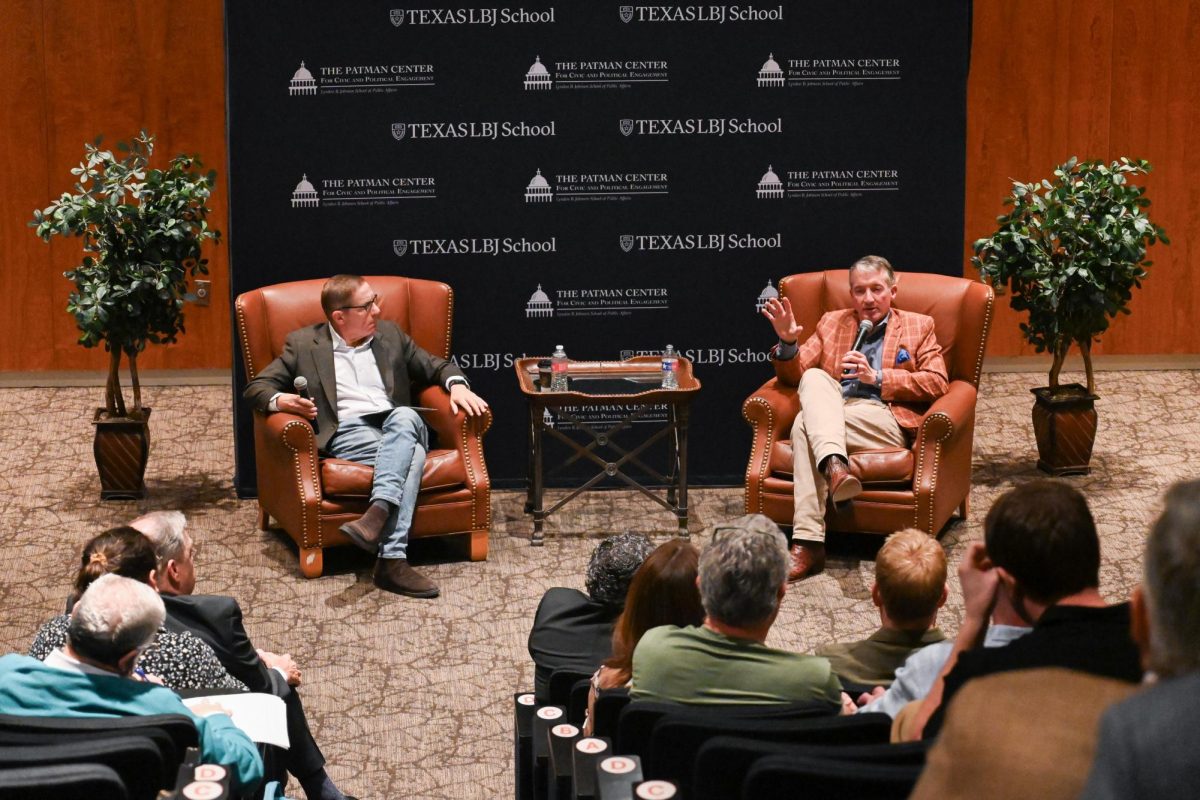

The rapid growth in China’s electronics industry in the 1990s was because of increased government investment and technological development, said Susan Mays, a research fellow at the LBJ School of Public Affairs, in a talk on campus Friday.

In a lecture hosted by the department of Asian studies, Mays focused on the development of semiconductors, which she said are the core electronic “brains” of a product. Semiconductors vary in size and are used in everything from microwaves to iPods. In 1995, China’s semiconductor industry only made up 2 percent of the global market, but 10 years later, that number had jumped to 25 percent, according to Mays.

“In the 1990s, if companies wanted to build a semiconductor plant in China, people would tell them they might as well go dig a hole in Shanghai and put their money in it, because they weren’t bringing in any profits,” Mays said. “By 2005, 18 out of 25 of the world’s largest semiconductor firms had design groups in China.”

Mays said one reason for this rapid improvement was the Chinese government’s willingness to invest in semiconductor businesses.

“[China] had the market and the demand for semiconductors but not the capital,” Mays said. “It’s hugely expensive to set up a semiconductor industry, so the government made a series of investments in certain electronics companies.”

Robert Oppenheim, associate professor of Asian studies, said China’s growth in the semiconductor industry was important because of the close economic relationship the country has with the U.S.

“It’s important for the U.S., and particularly students, to be aware of China’s growing economy, since we compete with them in the technology industry,” Oppenheim said.

Chinese companies ran into problems as they realized they didn’t have the manufacturing capacity or expertise to make products, Mays said.

“By industry standards, China was way behind,” Mays said. “They learned by doing. It was a trial-and-error process. They just wanted to get one enterprise up and running.”

Mays said improvements in management, technology and foreign partnerships helped bolster the industry’s success.

“[China] wanted to be like HP and Intel — to harness the creativity and passion of the younger generation,” Mays said. “[One company] hired a younger CEO and outsourced manufacturing to Taiwan, which finally made them a profit.”

Mays said China’s big breakthrough came when it convinced a Japanese semiconductor company, NEC, to partner with some of its electronic companies.

“At that time, China’s microchip market was doing fairly well,” Mays said. “China said, ‘Look, if you partner with us, we’ll give you our [microchip] market.’ Once they had foreign interest, the industry really took off.”

Government sophomore Josh Tsio said he thinks the increasingly global focus of China’s economy is vital for students to pay attention to.

“Everything is more integrated now, so I think it’s important as Americans for us to know what’s going on on the other side of the world, especially with all the globalization and industrialization,“ Tsio said.