While pursuing a psychology degree, Wendell Jones, a member of UT’s first gay student organization, was told by his adviser he should not pursue the degree since being gay made him unfit to give psychological advice to others.

This type of discrimination led to the formation of the Gay Liberation Front, also known as GLF, UT’s first gay student activist group in early 1970. In addition to protests and rallies, the group hosted the first GLF conference in spring of 1971, which brought together gay liberation groups from across the country.

While composed almost exclusively of UT students, the group was prevented by the University’s policy from meeting on campus or becoming an official student organization.

“The nation was just in incredible turmoil, but it was also a very exciting time when people were energized and felt that we could really build a better world,” Jones said.

Today, LGBTQ students and their GLF predecessors have different tactics and issues they are fighting for, but their underlying goal of equality has not changed.

“I think our goals are fundamentally the same as when we started seeing more LGBTQ visiblity on campus,” said Marisa Kent, co-coordinator for UT’s Queer Student Association. “But the one big shift is that we are more accepted on campus.”

Often faculty and staff members and students were supportive of gay students, but discrimination was common on campus in many forms. According to Randy Conner, UT alum and former GLF member, professors would sometimes alter grades if they discovered a student was homosexual.

“When I wrote an openly gay story, [my professor] totally flipped out and basically told me, after telling me I had great talent, that I had no talent,” Conner said.

Conner contributed to the group by teaching one of the University’s first LGBTQ literature classes. The course was informal, not for credit and free for all students.

“They made me call it ‘The Homophile in Literature,’ and no one used that term anymore,” Conner said. “That was a term from the ’50s. It was the only way they allowed me to teach the class.”

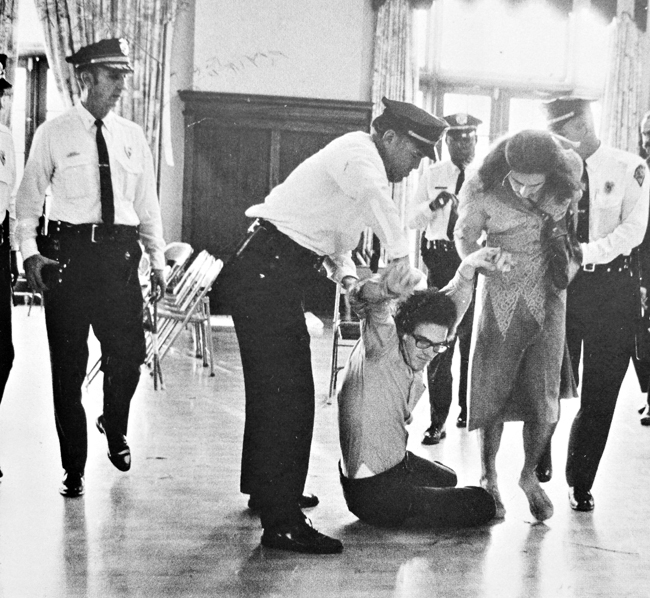

When UT did not recognize the group as an official student organization in the spring of 1972, GLF decided to sue the University. They raised money to sue through a school dance, which the then-dean Edward Price canceled at the last minute. Wendell and his peers refused to leave the area in protest and were arrested.

In jail, the police put Jones in a cell with an African-American man and told the stranger he could be violent toward Jones, stereotyping both men in the process. The man told Jones he had a gay brother [and that he] would not harm him.”

This further opened Jones’ eyes to the connection between all minority groups.

“I began realizing that there were certain common things that homosexuals shared with black people at that time, and my politics started getting much sharper,” Jones said. “I started wanting to work with other groups — not just the anti-war movement and the gay liberation movement — that were trying to create a better world.”

In the spring of 1974, the GLF was finally recognized as an official student organization. But, as the Vietnam War came to an end, the gay rights movement became more conservative — the once-connected movements became isolated, and the group lost momentum.

In 1976, Jones left UT to study law in California, and Conner graduated with his masters degree in English.

Current LGBTQ student groups owe their establishment to the efforts of the GLF.

“They had a hard fight to have the ability to form a group,” Kent said. “I think in that in itself, and what they were working towards, started opening the door for other groups to come in and form organizations based on their LGBTQ status.”

The issue of gay rights in regard to Proposition 8 will be discussed Tuesday, April 8 at 12:35 p.m. for the Civil Rights Summit.