Many students remain unaware of a policy that allows students to report alcohol-related emergencies without facing disciplinary action.

Although there are more students aware of the University Health Services’ alcohol amnesty policy this year than last year, the number of informed students remains low, according to results released from a survey distributed to students before spring break.

The Student Amnesty for Alcohol Emergencies program, set up in 2008, is currently being “relaunched” after UHS found that many students were still afraid to report alcohol-related emergencies because of the possibility of getting in trouble.

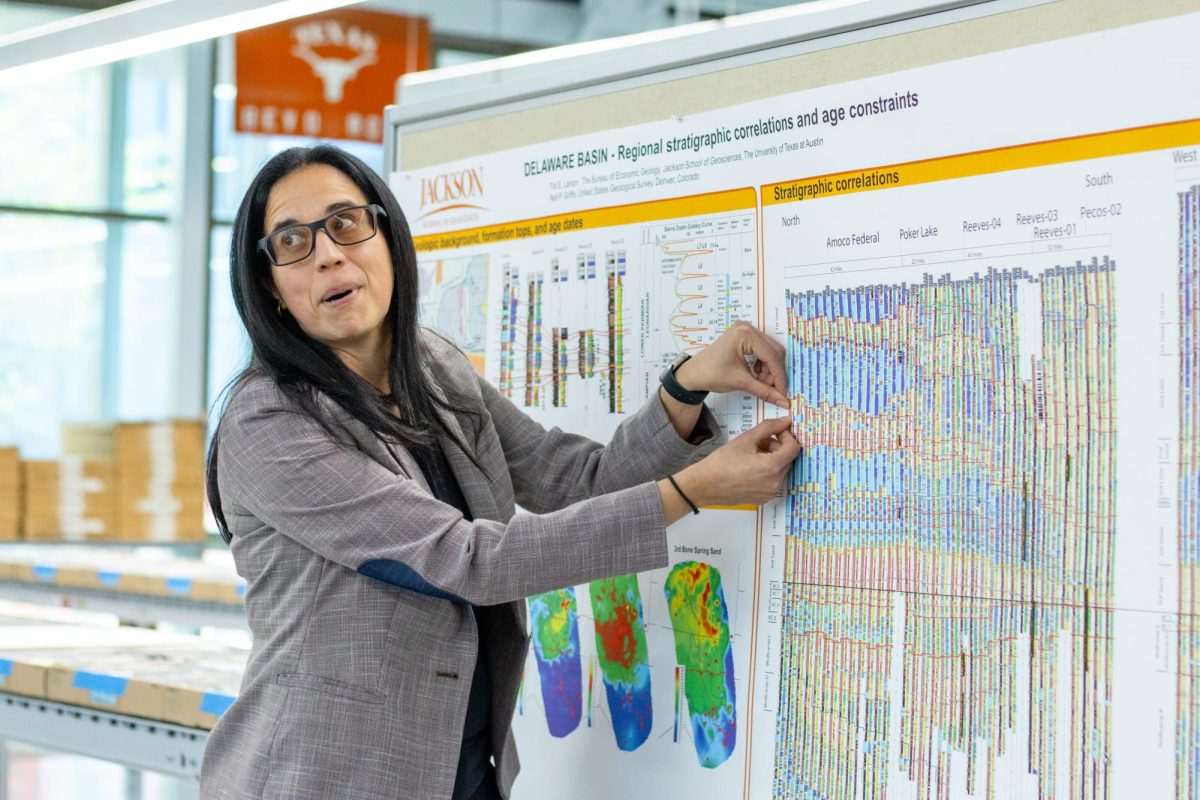

According to Frances Nguyen, health promotion coordinator at University Health Services, many students, when told about the policy, dismissed it as being too good to be true.

“A lot of what we found in our research is a lot of students have heard about it but don’t believe it exists,” Nguyen said.

In fall 2013, the National College Health Assessment found that only 6 percent of UT students surveyed knew about the amnesty program. Before spring break, UHS distributed a second survey and found 13.9 percent of the 724 students who completed the survey were familiar with the policy.

“It’s something that exists and we really want students to know about it,” Nguyen said. “It reduces that barrier that when students call 911, that should be their first reaction instead of worrying about what the disciplinary action should be.”

According to Jason Thibodeaux, director of Student Judicial Services, there were 199 cases involving alcohol on campus, and of those cases, 11 were deemed eligible for the amnesty program. He said most disciplinary action is taken when students in residence halls are left alone because their friends do not report the situation.

“If the people had reached out for help first, it wouldn’t be a disciplinary issue,” Thibodeaux said.

Thibodeaux said the low numbers of reports are due to the lack of students who are aware of the program.

“Honestly, when we meet with students they don’t even know about this amnesty policy until we bring it up,” Thibodeaux said. “We would be more than happy to have many situations of the policy. We’re not out to get people.”

Student Judicial Services and University Health Services will be working together through the summer to raise awareness of the policy among first year students and will attempt to make the program better known in the fall.

Jessica Duncan Cance, assistant professor in the department of kinesiology and health education, said the re-launch of the program would also give the University an opportunity to educate students about the signs of alcohol overdose.

“It’s a very thin yet scary line that takes somebody from being drunk to potentially at risk of an alcohol overdose,” Cance said.

Cance, who is a co-chair of UT’s Wellness Network’s High-Risk Drinking Prevention committee, said the students should know the signs of alcohol poisoning. According to Cance, the committee has been working to educate more students about the amnesty policy this semester.

Cance said signs of alcohol overdose include mental confusion, gasping for air, paleness of the skin and throwing up.

“Just like you know you should wear a seat belt every time you get in the car, this should be information that is just part of your sub-consciousness,” Cance said.

Cance said the amnesty policy should make students more willing to report alcohol related emergencies and make them less worried about the consequences.

“It’s better to have a friend be mad at you than to have a friend who has an extreme medical emergency,” Cance said. “That’s a much better thing to have to deal with than to have a death or somebody hospitalized because they had too much to drink.”