In 1971, Martha McClintock published a pilot study in Nature science journal as a sole author. This is an impressive feat, even for tenured professors, but she pulled it off as an undergraduate. The subject of her research? Menstrual synchrony, or the alleged synchronization of women’s menstrual cycles after living in close proximity to one another.

The “McClintock Effect” suggests that human pheromones are a reality and that hormones can be regulated purely by proximity, potentially leading the way to contraceptives or fertility treatments that work via scent alone. If confirmed, this McClintock Effect would have profound implications.

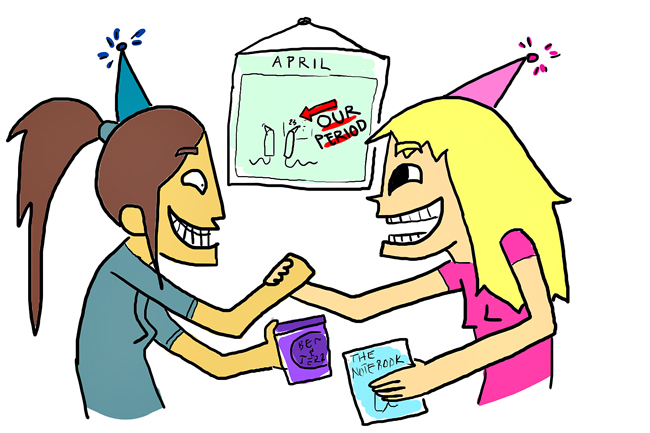

Unfortunately, attempts to replicate her results have been inconsistent and, also, a bit strange. Several studies used protocol that involved placing auxiliary extract, or a donor’s armpit sweat, underneath subjects’ noses. One study looked at female basketball players, noting the exciting notion of studying “not only a group of women but a group of perspiring women.” Despite these numerous attempts, there’s no strong sense of consistency in the research. In fact, several studies provide completely contradictory results. A search of the literature reveals one paper, “Menstrual Synchrony in Female Couples,” and another titled “No Evidence for Menstrual Synchrony in Female Couples.”

This inconsistency supports the null hypothesis that the McClintock Effect is a statistical artifact, a result of experimental bias or poor protocol and not a real phenomenon. If the average menstrual cycle is 30 days with menses lasting for five of them, there’s a 33 percent chance that any two women could have periods that would overlap during any given month. McClintock didn’t look for overlap to confirm her effect but, rather, simply looked for the dates between onsets to reduce over several months.

A paper published in 1992 looked at the multiple replication studies, in addition to McClintock’s original, and pointed out several errors. Among the most egregious was that, in the experiments with positive results, some subjects left the experiment early because of irregular cycles. With the small sample sizes involved in the trials, a few people dropping out could make a huge difference in the end result, especially if they left for reasons directly related to their periods.

McClintock still stands behind her pet theory, but with a few changes. She admits that menstrual synchrony is certainly a myth and described several misconceptions in a 1998 paper.

In picking apart the myth, however, she clouds the definition of what it is that she’s defending and notes that synchrony is not the only possible outcome of women living together.

“Some groups did indeed increase synchrony level,” McClintock said. “Other groups actually became more asynchronous. Moreover, some groups maintained exactly the same phase relationship over many cycles.”

In other words, any possible outcome potentially supports the McClintock Effect.

McClintock hasn’t met the burden of proof required to accept menstrual synchrony or even produced a falsifiable hypothesis describing it.

As for the bigger question of human pheromones, research suggests that their existence is likely, but not quite verifiable. There are studies supporting the idea, except many of them aren’t well controlled and some of them are very odd. In one study, researchers gave men a urine sample and asked them to guess the gender using their sense of smell. They found that men were better able to do so when the woman who produced the sample was closer to ovulation, although there are plenty of reasons to question the reliability of

this study.

Human sexuality is complicated, and pheromones do probably play a role in it, but so do visual, audio and tactile stimuli, as well as fantasy and imagination. Hormones are very much affected by the environment we’re living in and so, too, are menstrual cycles, which can be delayed as a result of breast-feeding, stress or weight loss, among other factors. It’s not completely implausible that the people we surround ourselves with can also affect when periods occur. But, as of right now, the evidence doesn’t support that conclusion.