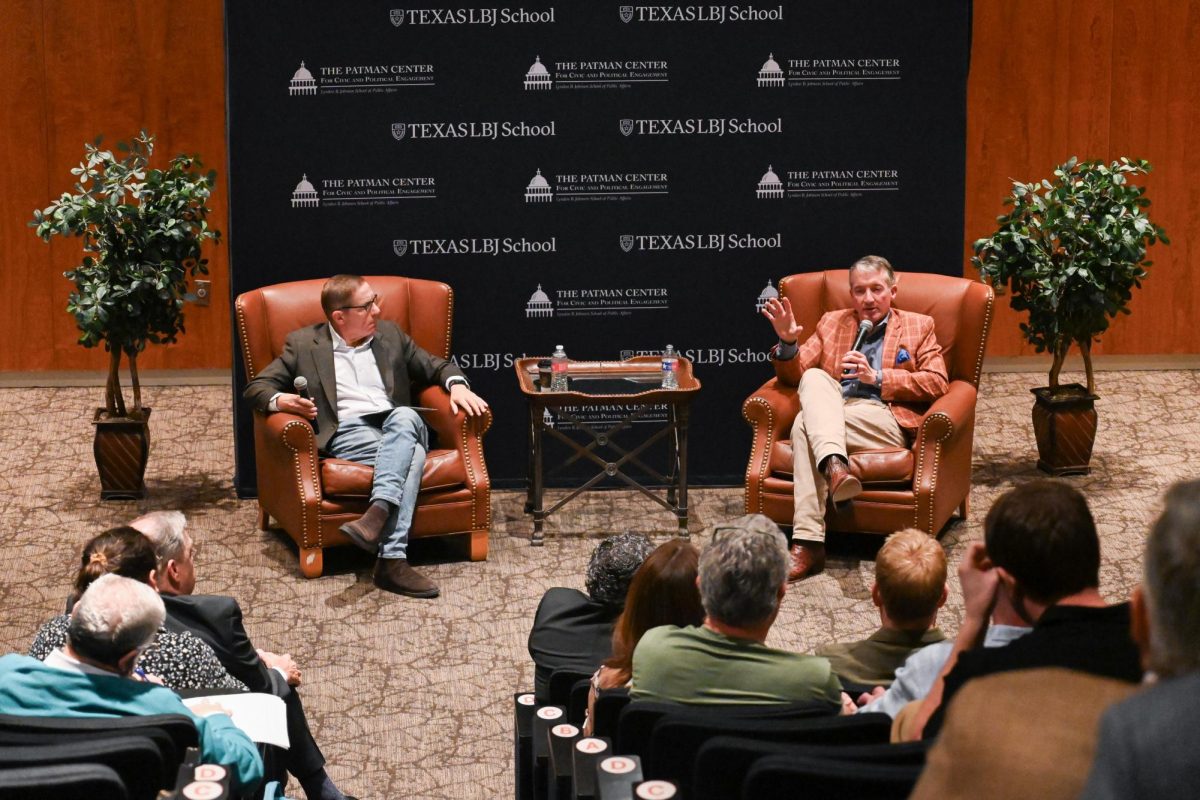

A faculty panel discussed the controversy and historical background surrounding “Gone with the Wind” on Wednesday as part of the Harry Ransom Center’s ongoing exhibition, “The Making of Gone With the Wind.”

“Gone With the Wind” was originally a book written in 1936 by Margaret Mitchell but was brought to the big screen in 1939 and was directed by David Selznick. The film was referred to as a classic of the golden age of Hollywood movies. At the time, it sparked controversy over how it portrayed sex, race and

violence in the South during both the Civil War and the Reconstruction Era.

According to Jacqueline Jones, history department chair, “hate mail” was sent before and during production of the movie from radical labor groups, veteran groups and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

“They were eloquent statements about the book and how the Union veterans were depicted and how African-Americans were depicted,” Jones said. “They gave a sense of the real controversy that began even before production.”

History associate professor Daina Berry said that during the 1920s and 1930s, many African-Americans were frequently interviewed by media outlets because they were the last descendants of slaves. Despite this, African-Americans were typically portrayed by white actors in films.

“We didn’t have a lot of visual representations of African-Americans during this time period,” Berry said. “This was a film that you finally had African-American actors and actresses playing slaves on stage.”

The protagonist in the film is Scarlett O’Hara, a southern belle who is the daughter of a plantation owner in Georgia. According to Jones, a sort of “melodrama” ensues from Scarlett’s romance and conflicts. Jones said that Scarlett, played by Vivien Leigh in the film, starts out as a spoiled brat on a plantation and transforms into a self-reliant lumber dealer.

“Scarlett embodies this new South,” Jones said. “She’s very enterprising, becomes obsessed with money and really lost touch with the value of the land. She’s become self-reliant, and that’s what some young women reacted to.”

Radio-television-film professor Thomas Schatz said that during the time period the movie was one of the first to have a female lead.

“The female audience was so important to Hollywood at the time,” said Schatz. “What this movie was doing with race and gender was so wonderfully complicated, and it’s the way Hollywood intended it to function.”

The exhibit for the film includes on-set photographs, audition footage and fan mail. It will be available for free tours at the Harry Ransom Center until Jan. 4.