You may not understand why you dreamed about riding Bevo naked down Sixth Street last night, but neither do the best scientists in the field of

dream research.

Scientists have several theories on why we dream, but none are complete. Freud believed dreams represent wish-fulfillment; however, this theory has fallen out of fashion for more complex hypotheses.

One of these hypotheses posits that dreams connect memories in the brain, using the dreamer’s emotion as a guide.

Another, referred to as “threat simulation theory,” assumes dreams are an evolutionary adaptation that prepare you for future dangers.

In a paper published in 1993 and revised in 2000, George Wiliam Domhoff, University of California- Santa Cruz sociology professor, attempts to show threat simulation theory is incompatible with current dream research.

Domhoff looked at studies of people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, which showed that people often experience severe nightmares relating to personal traumas. Dreams make it more difficult for PTSD victims to sleep at night and deal with their past experiences.

Domhoff also notes nightmares more commonly occur in people experiencing stressful situations or those more sensitive to mild stressors of everyday life, such as feeling like an outsider or being self-conscious.

Threat simulation theory predicts dreams should anticipate difficult situations. Instead, the nightmares are a response to them.

This isn’t enough to throw out threat simulation theory completely, but it does show that dreams are complicated and may not have a specific purpose.

Perhaps the most difficult type of dream to explain is the lucid dream. During lucid-dreaming situations, dreamers know they are dreaming and can sometimes control their surroundings. Researchers have investigated these self-aware states, and, while they’re interesting, they’re tricky to study.

To prepare for one experiment, researchers enlisted 20 participants to take place in weekly lucid dream training sessions. After four months, only six could become lucid three times or more per week.

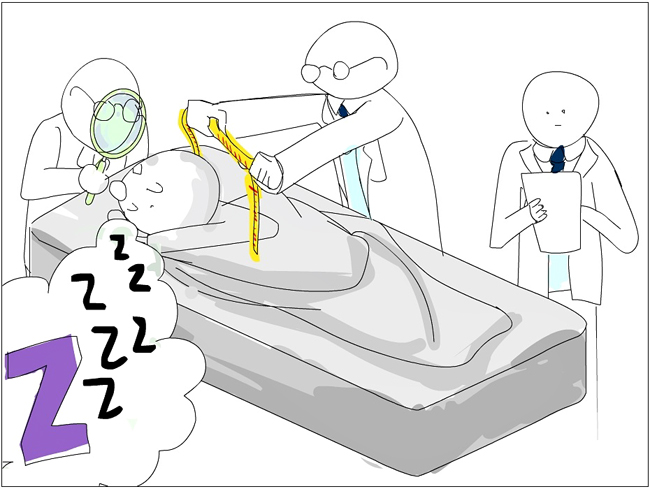

For the study, subjects slept with monitors attached to their heads to measure brain waves so that scientists could learn the differences between traditional dreams and lucid ones.

How can researchers know for certain the subjects are lucid dreaming? By monitoring the subjects’ eyes.

The scientists told subjects to move their eyes in a predesignated pattern when they realized they were dreaming: left, right, left, then pause and repeat. This caused the subjects’ eyes to move in the dream as well as in the real world, so scientists could determine the exact moment someone learned they were in a lucid dream.

The problem is that subjects reported more difficulty in achieving lucid states in the lab. Perhaps this is because of performance anxiety, but it may also be because of the difficulty in trying to sleep with EEG cables attached to their heads.

As a result, although the six subjects could reliably have lucid dreams on their own, only three managed

to produce a lucid dream during the course of the actual experiment.

Despite small sample size, the researchers produced evidence suggesting that lucid dreaming is more like a state of being half awake and half

in a dream.

We may not be close to understanding dreams, but mystery is part of the fun of science. You’ve got as good a dream laboratory in your head as any researcher, so the next time you notice you’re dreaming, why not move your eyes around and run a few experiments?