Over two hundred million miles away from Earth, there is a planet shaped solely by wind.

Geosciences postdoctoral student Mackenzie Day recently discovered that the mounds on Mars’s surface have been shaped by the force of wind.

“There has been a lot of debate in the past few years about how these mounds form — whether it is depositional or erosional or if they form from wind or water,” Day said.

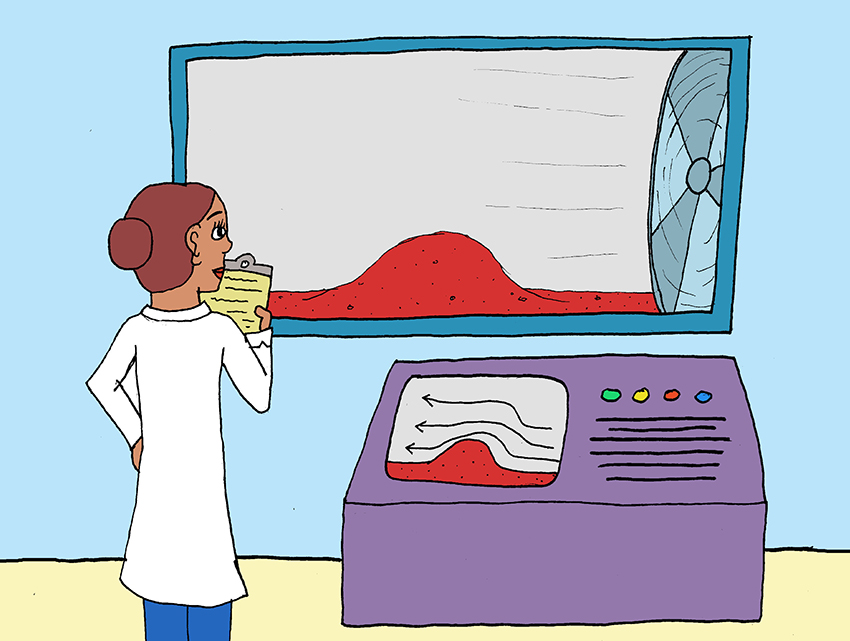

To answer this question, Day placed small model craters inside a wind tunnel and allowed all material to erode away. The result was a mound shape that exactly mirrors those seen on Mars today. Day worked with geosciences professor Gary Kocurek and other researchers to then construct a computer model that simulated wind’s effects on craters and supported their findings.

“You get a moat, and it cuts deeper and deeper until you get your mound shape, which then erodes away towards the center and is eventually completely gone,” Day said.

Unlike Earth, Mars has no plate tectonics or running water to naturally form its landscapes. Instead, the slow-acting force of wind is dominant on the red planet.Kocurek said that wind, which has been acting on Mars for billions of years, has significantly changed the landscape.

“If you are an aeolian sedimentologist, Mars is kind of like the ultimate national laboratory,” Kocurek said. “You can really see what would happen if you had no plate tectonics, no flowing water and plenty of time, what wind could do.”

Both Kocurek and Day emphasized the differences between the landscapes on Earth and Mars, noting that people on Earth are more familiar with faster-acting forces of nature. This is one reason why humans might find the Martian landscape strange.

“We would notice [the effect of wind] more if we went to Mars because the landscape would have a whole different look to it,” Kocurek said. “If you walk outside now, what do you see? You see Waller Creek, you see hills eroded by flowing water, you see gullies, but you wouldn’t see any of that on Mars.”

The team is only able to observe Mars through satellites and the Curiosity Rover, which is stationed at the crater they are studying. Day said that it is difficult to compare results from an experiment on Earth to the same experiment on Mars because all physical model experimentation on Earth is subject to a specific gravity. On the other hand, Kocurek said that while Mars is a separate planet, the same basic rules of science apply.

“If there is any sense to the universe at all, the same physics works,” Kocurek said. “You don’t have to go into an imaginary world to understand it. The same universal laws work.”

Modeling the formation of Martian mounds has given the researchers more information about how the planet as a whole has changed over time. Day said that knowing these mounds started with lots of deposited material allows for a better understanding of climate change on Mars.

“[A lot of people have suggested] the environment in which the original material was deposited was a wetter, an earlier Mars,” Day said. “So that puts your early, wet, fluvial Mars before the dry, erosional environment that you have today.”

Day and Kocurek both have the goal of learning more about places dominated by wind — and specifically how these places differ from Earth.

“Moving forward, one of the things we will do is start comparing the two planets and see what conditions on one might affect what we see at a landscape scale,” Day said.