Behind the scenes of nearly every big blockbuster movie is a cast and crew made up almost entirely of men.

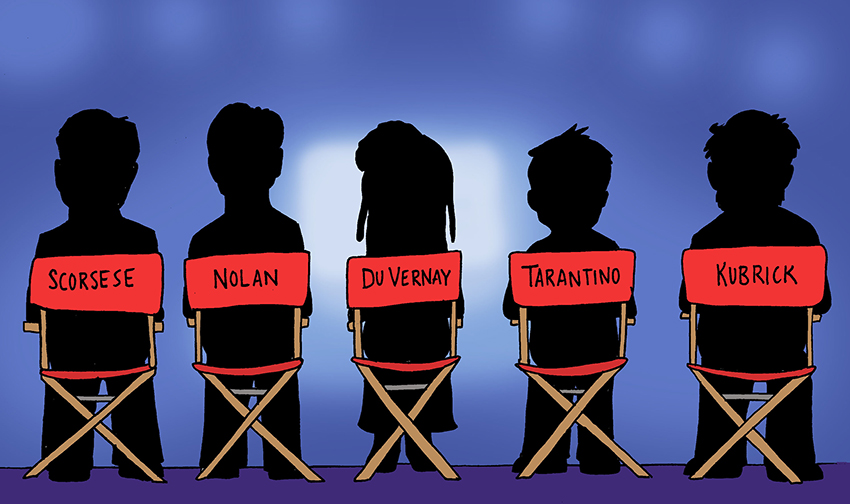

According to a study conducted by Martha M. Lauzen, executive director of the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, 91 percent of directorial positions are occupied by men. In addition, a mere 19 percent of writers, directors, cinematographers, editors, producers and executive producers on 2015’s top 250 domestic grossing films were women.

These statistics indicate a divide in employment that traces back to the birth of Hollywood. Radio-television-film professor Ellen Spiro said the industry’s hesitance to employ women led them to pursue less popular genres, such as documentary.

“The history behind [women’s success in documentary filmmaking] is that documentary used to be a field with no money or interest,” Spiro said. “As a result, women could excel and not be discriminated against, and women like Sheila Nevins, the president of HBO Documentary Films, built documentaries into something very powerful.”

Even in documentary filmmaking, women remained unequal to their male counterparts, accounting for 36 percent of all individuals behind the scenes in 2015. Comedy, at 34 percent female employment, yielded similar representation, and genres with stereotypically male viewership — such as action and horror — generated crews where women accounted for 9 percent and 11 percent of employees, respectively.

Though these numbers can be discouraging to females aspiring to work in the film industry, radio-television-film freshmen Rikki Bleiweiss, Kelsey Linberg and Claire Norris — who collaborated to write, direct and produce Texas Student Television’s new show “Midsummer Nights at Jenny’s” — remain hopeful about securing lead positions in Hollywood.

Bleiweiss, co-writer and co-producer of the show, said she feels that the lack of female representation in the industry can be attributed to the standardization of material catered toward men.

“Nobody watches a show like ‘The Big Bang Theory’ and thinks ‘Wow, that was so much dude humor,’ but people think that way about [female humor in] ‘Broad City,’” Bleiweiss said. “There is this assumption that the normal form of comedy — the form of comedy that’s most accessible and that everyone is expected to write to — is for a male audience, and that’s extremely unfortunate.”

Linberg, fellow co-writer and co-producer, said male-centered material has already influenced how women become active in the industry.

“Because a woman’s perspective is seen as separate from the general perspective, women in comedy have had to create their own shows, written from their own perspectives because other people have difficulty taking their humor as seriously as they take men’s humor,” Linberg said.

Some media theorists argue the film industry’s desire to profit from male-produced, and consequently male-centered, material has likewise silenced conversations about the representation of women offscreen. Norris, director of “Midsummer Nights at Jenny’s,” said she hopes these conversations continue among cinephiles and leaders in Hollywood.

“My hope for the industry is that we are able to talk about [gender disparity] more so that people, especially men in power, understand the gravity of what’s going on,” Norris said. “If the responsibility to secure employment for women falls solely on the women, how can we expect progress in the industry? Everybody needs to work together. It’s not just a problem for the women being affected by it.”