RIO DE JANEIRO – When junior swimmer Joseph Schooling finished his 100-meter butterfly race at the Rio Olympics, he looked back to see his time of 50.39 seconds — three-quarters of a second faster than Michael Phelps.

For 15 years, Schooling dreamed of competing on swimming’s biggest stage. He spent every year chasing his idol Phelps, stacking up their stats as he improved.

Before the race, he approached his starting block, trying to ignore the deafening reception from the crowd for Phelps. He had a simple plan that hadn’t changed since he’d arrived in Rio: Get his hand on the wall first.

The race was close — Phelps, South Africa’s Chad Le Clos and Hungary’s László Cseh finished in a three-way tie. But ahead of the pack was Schooling, ecstatic in the triumph he’d been working toward for more than 10 years. Before this, Phelps had taken gold in every Olympic 100-meter butterfly race since Athens in 2004.

Not only had he just beaten his idol, he also shattered the Olympic record time in the event and earned Singapore’s first-ever Olympic gold medal.

“I’m just ecstatic,” Schooling said. “I don’t think it has set in yet, it’s just crazy. You know, breaking the Olympic record and it was a thrill to swim against Michael Phelps and all those guys.”

Phelps, Le Clos and Cseh were his biggest competition but also his biggest motivators. After meeting Phelps as a teenager in 2013, Schooling said he dreamed about achieving similar success.

“Without [those] guys next to me, I don’t think I could’ve gone as fast,” Schooling said. “I think growing up most swimmers idolized Michael Phelps. He’s the perfect guy to dream of accomplishing what he has accomplished. One gold medal is nuts. I can’t imagine 22 or 23. I wanted to be like him, to be so victorious. A lot of this is because of Michael. He’s the reason why I want to be a better swimmer.”

Phelps reflected on their first meeting at a press conference after the race. He encouraged reporters to focus their questions on Schooling, who he said represented the sport’s future.

“I’ve been able to watch him grow and turn into the swimmer that he is, what he is able to achieve [now] is up to him,” Phelps said.

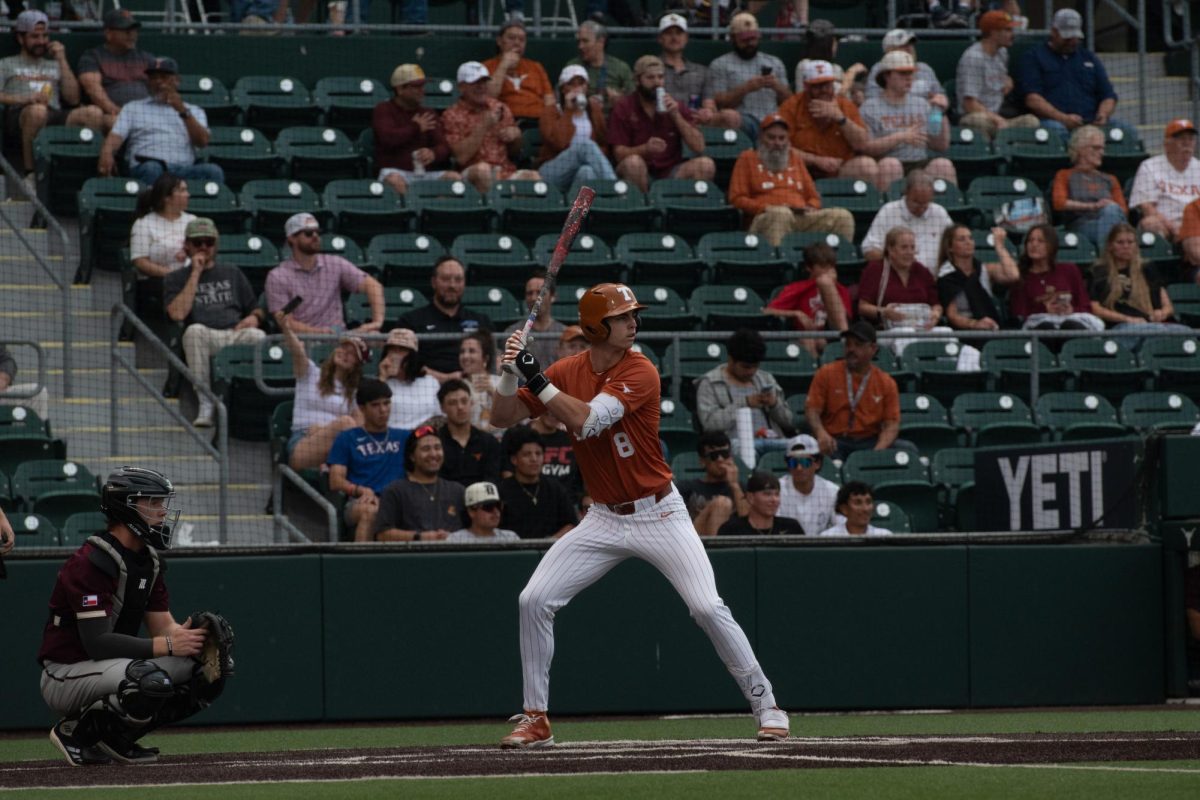

The 21-year-old Longhorn was born in Singapore and trained there until his second year of secondary school, when he moved to the U.S. to swim competitively.

In 2013, Schooling applied to defer his mandatory two-year National Service requirement in Singapore. Believed to have a credible shot at a medal, Schooling’s application was approved. And shortly after, he left for the University of Texas to train under coach Eddie Reese.

Schooling will have to apply again for another deferment if he hopes to compete in Tokyo in 2020. Singaporeans took to social media quickly after the race to voice their support for a second deferment for the swimmer.

In an interview with TODAY, Oon Jin Teik, the Singapore Swimming Association’s Secretary-General, fully supported allowing Schooling to continue training and competing.

“I think it’s not just me hoping that Joseph will get another [NS] deferment,” Teik said. “I think the whole of Singapore will ask for him to defer at the rate he’s going.”

Schooling said winning a gold medal was an incredible feeling. But he felt it meant even more for his family and the country of Singapore.

“I think when you race for people greater than yourself, it really means a lot when you accomplish what you wanted to,” Schooling said. “I hope this paves a new road for sports in Singapore. I hope it shows that people from the smallest countries in the world can do extraordinary things.”