Editor's note: This is part of a compilation of stories highlighting the experiences of students struggling to achieve equal representation on campus.

Heman Marion Sweatt sees $27,000 in cash lying on the table before him. Taking the money means dropping his lawsuit against UT and never attending the University’s law school. It was a bribe he wasn’t willing to take.

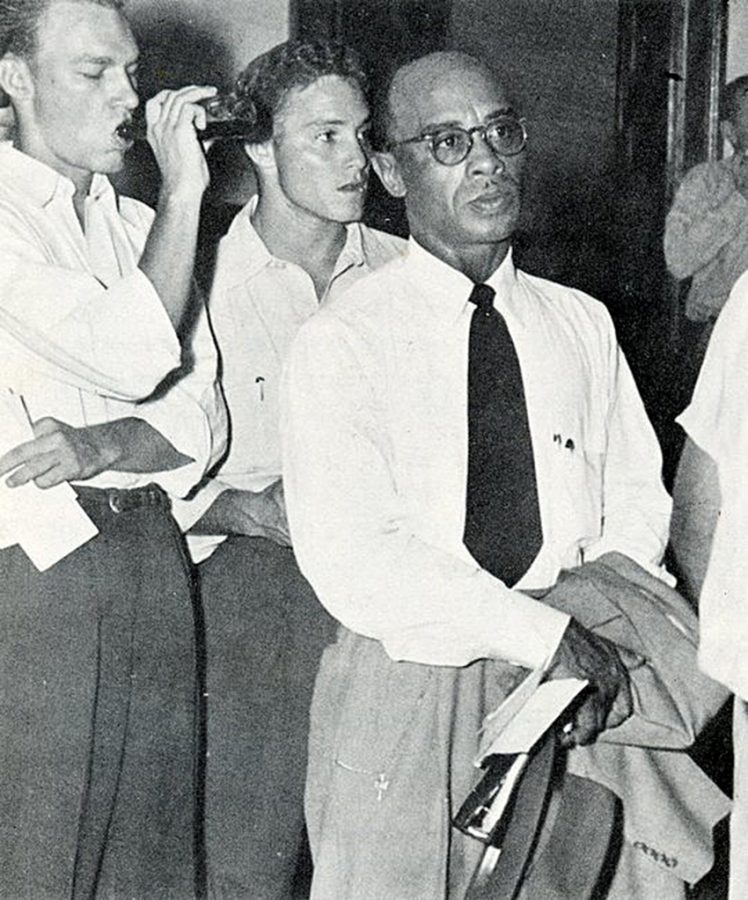

Seventy years ago, Sweatt filed a lawsuit against then-University president Theophilus Painter. Sweatt, a black man, applied to the UT School of Law in 1946 and was denied admittance because of his race.

His suit challenged the “separate but equal” doctrine that permitted segregation of blacks and whites under Plessy v. Ferguson. Though it was initially denied by the Texas District Court, the case eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. On June 5, 1950 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Sweatt, stating that the blacks-only law school the University tried to create in the alloted six-month period was inherently unequal. The court required the University to accept Sweatt.

Even though he had been admitted, his time at UT would prove to be just as difficult as the admittance process.

“He talked about how he’d go to class and he’d have screens set up around his desk sectioning him off or he’d be moved out into the hallway,” said his great nephew, Heman Marion Sweat II. “He had made quite a few friends who were really concerned for his safety, and they would walk him after class to his car.”

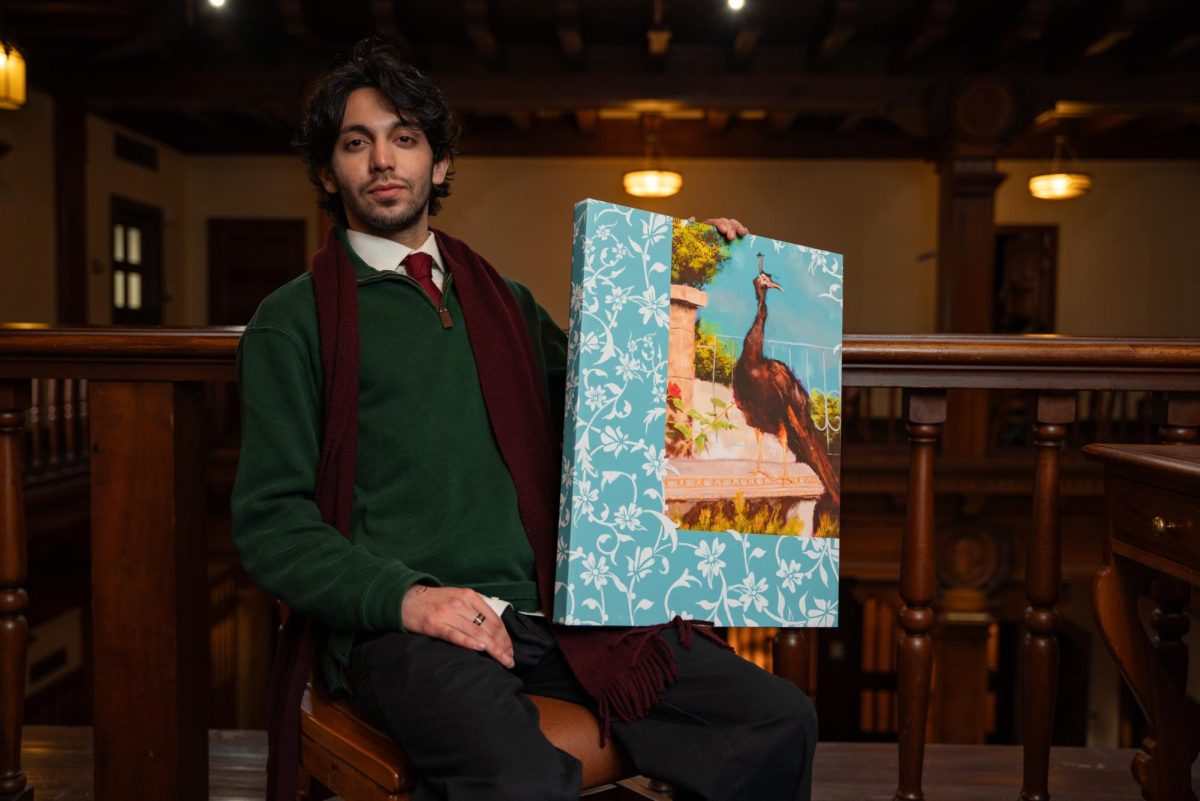

Sweatt II was born on June 30, 1950. While he didn’t spend much time with his great uncle growing up, he knew his name was full of history. As he learned more about his great uncle, it drove him to live up to the expectations that came with their shared name.

“[His legacy] drove me to do try harder,” Sweatt II said. “When I was real young, it was likely a burden, but as I got older and I started learning about his impact on education in Texas, it gave me something to shoot for.”

In 1968, 18 years after his great uncle was admitted, Sweatt II attended UT. While the campus atmosphere was more accepting of black students than it was in the ’50s, Sweatt II still felt disdain from his classmates. He said campus police officers would frequently stop him to ask for his ID while white students walked uninhibited around campus.

“There were a number of times where I felt excluded from the conversation,” Sweatt II said. “There was always that feeling that all those people smiling in your face did not really want to be bothered with you or any other minority student on campus. Everything that black students gained on UT campus had to be petitioned for.”

Sweatt II sent his great uncle Heman a letter to share the news of his acceptance, and his great uncle was delighted. While he was never able to finish law school, he hoped Sweatt II would continue his education.

“He always tried to encourage me and my cousin to stick with [education] and not let anything distract or deter [us],” Sweatt II said.

Sweatt developed major health problems due in part to the stress of the lawsuit and died in 1982. While his uncle is survived by the lasting impact of his Supreme Court case, Sweatt II said there is still progress to be made.

“[We should] stop prejudging and collectively [labeling] a group of people,” Sweatt II said. “If you open up the door and let everyone compete freely, I think people begin to realize and see, with my uncle’s case and moving forward, that the color of the skin doesn’t determine how much knowledge you can gain or how educated you are.”