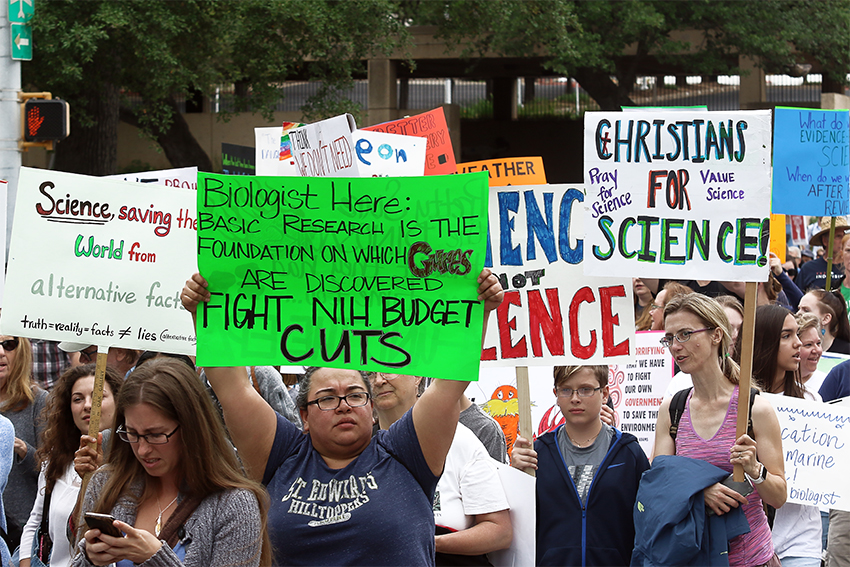

The March for Science, which drew protesters across the country and around the globe into the streets on Saturday, presents a kind of contradiction. Implicitly if not explicitly, the march was a reaction to the anti-science policies of President Donald Trump, who denies the reality of anthropogenic climate change and flirts with baseless and harmful vaccine conspiracy theories. In this sense it was a march against the politicization of science. But as a political protest, the march itself was just that — an example of politicized science.

Does the March for Science contradict itself? Perhaps. But then, it certainly contains multitudes — in Washington alone, turnout reportedly numbered in the hundreds of thousands. Most of those protesters would probably agree science has a role to play in politics, but that politics should stay out of science. Facts over “alternative facts,” etc.

Nevertheless, the sentiment that science should remain above politics is popular across the political spectrum. You hear liberals invoke it in debates over climate change, and conservatives invoke it — somewhat disingenuously, I might add — in debates over abortion and the rights of LGBTQ people.

But if science should remain above politics, then what is it actually for? If values like “good” and “bad” are irrelevant to the work of better understanding the world around us, then what “good” can that work possibly be? When scientists discover that smoking causes cancer, what do they do with that knowledge? Leave it out there for tobacco companies to distort before it reaches the general public? Or take an active role in its dissemination, interpretation and ultimately political ramifications?

To the extent that politics and science have a history of working together, it’s not necessarily a very promising one. In the past, politicians and political actors have co-opted scientific learning and used debunked racial theories to justify systemic discrimination, disenfranchisement and worse. To this day, racists and sexists still use junk science to justify their hatred and delusion.

But if the marriage of science and politics can be used to achieve harm, then surely it can also be used to achieve good. Politics and science are constantly intersecting whether politicians and scientists like it or not. The most well-known examples usually involve the reverberations of science in the political world: in climate policy, in public health policy and so on. But politics also have reverberations in the scientific world, which has a well-documented diversity problem: According to the National Science Foundation, 84 percent of people working in science or engineering fields in the U.S. are white or Asian males.

The scientific community would benefit from greater diversity, but that can’t be achieved without some political literacy. American politics would benefit from an informed consensus on the facts regarding pressing issues like climate change, but that can’t be achieved without some scientific literacy. A wide gulf between science and politics isn’t just unrealistic; attempting to maintain one is harmful to both fields, and to the fabric of our society.

Groves is a government sophomore from Dallas. He is a Senior Columnist. Follow him on Twitter @samgroves