Austin’s rapid development is a lot like a rainstorm over dry, cracked earth: It inevitably permeates every open crevice. But as city officials rewrite Austin’s land development code, some see a bright side to the city’s future growth: a chance to expand Austin’s creative sector.

Over the past six months, Austin has been rewriting its antiquated land development code in a multi-year project called CodeNEXT. David Sullivan, a member of the CodeNEXT advisory group, has drafted an addition to the code that would encourage the growth of cultural districts all around Austin.

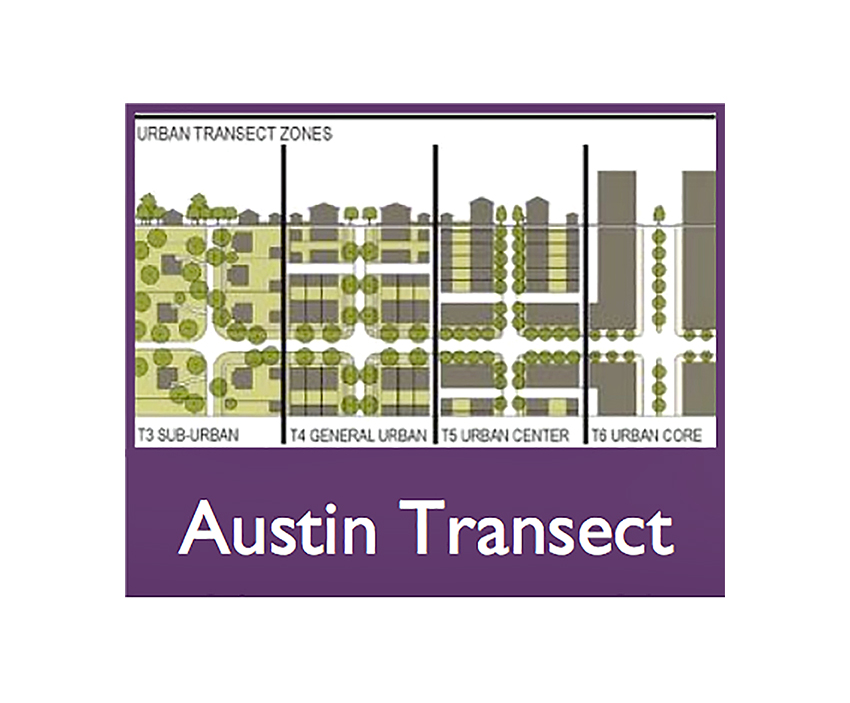

In the first draft of the code, city planners implemented a new zoning classification called ‘transect zones,’ which would avoid dividing the city into districts with pre-designated purposes in favor of creating transects, or mini-cities, across a larger urban area. However, after widespread confusion over the new concept, city officials announced last week that they would remove the transect classification from CodeNEXT’s second draft.

Although the idea behind Sullivan’s proposed addition is in line with the transect model — density spread over a larger area, rather than condensed into a central district — he said he isn’t concerned that officials are dropping the classification in the next draft of the code because the underlying concept of a transect is still intact.

“There is a misinterpretation of this change,” Sullivan said. “It’s a nomenclature change.”

Rather than calling them transects, Sullivan describes these spaces of potential growth as ‘regional centers.’

“Think of the Domain and the surrounding area, or the Highland Mall area,” Sullivan said. “For the purpose of art, music and culture, (the addition) would allow the same uses as we allow downtown.”

Brett Barnes, a member of the Austin Arts Commission, said when thinking about the future of Austin’s creative sector, it’s important to consider access.

“We need to make sure there are multiple places where people can consume (all types) of art,” Barnes said. “it’s important to make sure they’re accessible for everybody.”

Sullivan said even though he foresees people opposing the expansion of arts in neighborhoods, there will ultimately be more people who approve of the idea.

“You’re talking about the same attraction as a park,” Sullivan said. “There are people that are against parks (because) they don’t want people coming (to their neighborhood). But I’m pretty sure that most people would like to have an arts district near them.”

Sullivan’s proposed addition wouldn’t just permit the development of galleries and music venues across the city. It would also allow artists to live, work and sell their art in the same place, potentially helping solve one of Austin’s most pressing problems: affordability.

However, concerns over rapid commercial development prompt some neighborhood communities to reject development proposals, even if affordable housing is written into the plan.

Shawn Somerville, chair of the Land Use and Design committee of the East Cesar Chavez Neighborhood Planning Team, said neighborhoods in Austin tend to harbor skepticism toward development, especially the East Cesar Chavez neighborhood, where demands for affordable housing are rarely met.

“Neighborhoods don’t trust developers,” Somerville said. “They ask for double or triple the amount of affordable housing that the developer is offering, and when the developer says no, the plan doesn’t go through.”

Although he understands his neighborhood’s concerns over development, Somerville, who plays viola in the Austin Symphony, said he could see the benefits of allowing more units on a piece of property.

“I think is a good thing, especially if you’re an artist like me, because if you can make your house a duplex,” Somerville said. “Then, you may actually have a chance of staying in the neighborhood that you live in.”

Somerville said he also wants to see more theater and performance spaces in Austin, but caution will be needed when writing that development into the new code.

“The more intense our code gets, the more it kills creativity,” Somerville said. “If it’s not done right, it could end up hurting creativity rather than promoting it.”