A treatment and research program called the Body Project helps women learn to celebrate their bodies while delving into the neuroscience behind eating disorders.

Started in the 1990s, the Body Project aims to provide a preventative therapy that intervenes and stops the onset of eating disorders beforehand. It is found at over 100 universities across the nation, including UT.

“The Body Project treatment is a two eight-week dissonance-based eating disorder intervention,” said Amber Borcyk, UT Body Project coordinator for the past two years. “We collect self-reported data as well as neuroimaging and genetic sampling from participants. The groups undergo verbal, written and behavioral activities in which they discuss the costs of pursuing the thin ideal and the behaviors they use to pursue this ideal.”

While therapy does exist today to help treat eating disorders, the Body Project is different in that it serves to prevent eating disorders in women that show signs of developing one, according to project founder Eric Stice, a clinical psychologist from the Oregon Research Institute.

“The body project allows young women who are pursuing an unrealistic body type personified in the mass media … basically to talk themselves out of it,” said Stice, who is also a UT psychology adjunct associate professor.

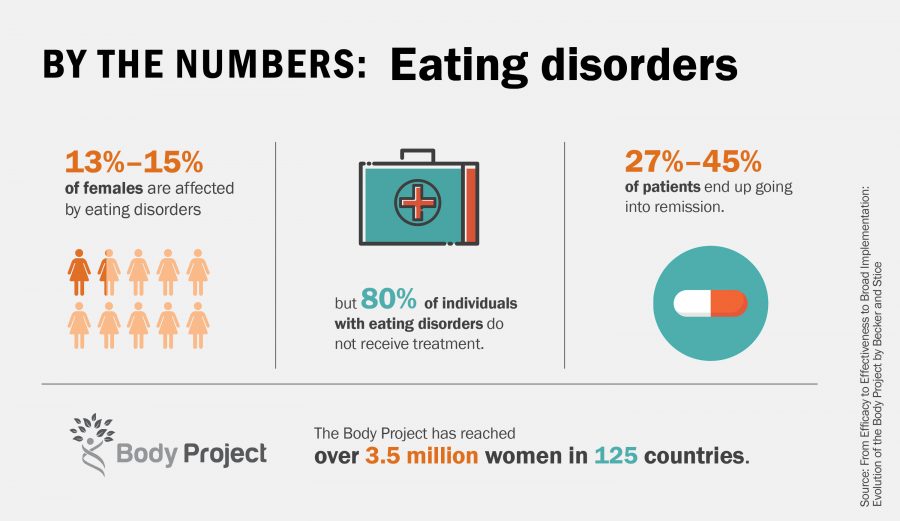

According to the Evolution of the Body Project report by Stice and Trinity University psychology professor Carolyn Becker, up to 15 percent of women will experience an eating disorder in their lifetime. Of those, only 20 percent will receive treatment, and 27 to 45 percent of patients will then go into remission and continue on with the eating disorder.

Many of the group activities strive to challenge unhealthy eating behaviors and the “thin ideal,” which is an unattainable body standard set by society, according to Stephanie Oleson, psychology graduate student and group instructor.

“The thin ideal is this pursuit of the perfect model-thin body,” Oleson said. “It’s kind of like this ultra-thin but also busty woman that really is unobtainable and also the idea that people go to extreme behaviors to achieve that thin ideal.”

To challenge the thin ideal, instructors promote the “healthy ideal,” providing women with knowledge on exercise and living a healthy lifestyle, Oleson said.

Aside from the group sessions, researchers with the program also study member brain images and genotypes, collecting a vast array of psychological, neurological and genetic data, Stice said.

“We were able to identify some really nice predictors of weight gain using (neuroimaging),” Stice said. “Give people a chocolate milkshake in the scanner and look at reward region response to that to predict future weight gain, and the predicted facts blow everything else out of the water.”

These techniques have also been used to verify the success of the Body Project group sessions, Stice added.

“We’ve done brain imaging work and shown that basically before women do the Body Project, when we show them pictures of supermodels and then average weight women, there’s really strong recruitment of reward regions when they see a supermodel compared to average rate women,” Stice said. “And after they do the body project, its reversed.”

According to Stice, the Body Project is following a group of women to see how results vary between women who received the traditional group therapy, women who received therapy from a peer educator, who is an undergraduate delivering the Body Project to other undergraduates, and women who received therapy from an online instructional video.

The third trial will begin shortly, and the lab is looking to find women interested in receiving free treatment. This is meant to be a treatment, not a preventative therapy, and is for women who already have an eating disorder, Stice said.

“Roughly, there (are) probably over 5,000 young women attending the University of Texas today that have some kind of eating disorder that they could be treated (for),” Stice said.

“It’s just totally mind-boggling if you think about the numbers that way.”

Stice said he expects to continue seeing growth to different universities, high schools, middle schools and certain sororities.

“Body image issues are one of the most significant problems with young women in college,” Stice said. “Having a good intervention that helps resolve problems is really fantastic … it’s exciting to have a program that works that anybody and their mother can implement.”