On Sept. 15, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft ended its 13-year mission with a “death dive” into Saturn. But this wasn’t a suicide mission: Cassini was actually following planetary protection protocol, said G. Fritz Benedict, a senior research scientist at UT’s McDonald Observatory.

Ultimately, this death dive was also the mission’s most prudent possible ending. Destroying the Cassini orbiter would avoid potentially contaminating Saturn’s satellites such as the moon Enceladus, which potentially has life-friendly conditions, with Earth’s microbes. This way, if life is discovered in Saturn’s system in the future, researchers may be certain that it is truly alien, said Laurence Trafton, a senior research scientist in UT’s astronomy department.

“Had Cassini crashed on, say, Enceladus, it might have contaminated a pristine, completely alien environment,” Benedict said. “What if our microbes are stronger, faster, more aggressive than any living (organism) in the oceans of Enceladus? Bye-bye to the natives and an opportunity to answer those questions about life.”

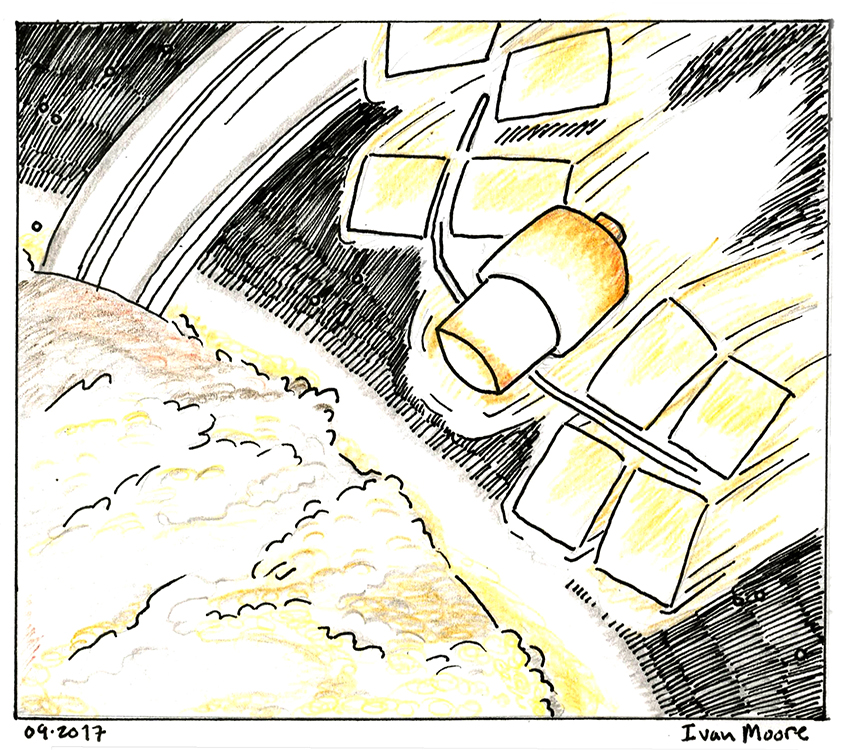

The satellite was immediately destroyed upon entering Saturn’s atmosphere.

“Like for a meteor on Earth, the main destructive factor is the energy (and) high speed of the falling spacecraft and the increasing drag of the atmosphere, which frictionally heats up and forcefully destroys the spacecraft,” Trafton said.

Space shuttles are able to protect themselves against this via ceramic heat shields that prevent the outer metal body from melting, but Cassini had no shield, Trafton said.

Cassini was just half of a joint mission; its other half was the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe that landed on Titan, one of Saturn’s moons, in 2005. Huygens survived on Titan for approximately four hours on built-in batteries.

“Any tears shed on (Huygens’) demise were shed long ago,” Benedict said.

According to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory website, the international Cassini-Huygens mission was not only the first to orbit Saturn and its system, but also the most distant planetary orbiter ever launched.

Cassini had the task of collecting and relaying information about the density and pressure of Saturn’s upper atmosphere, Trafton said. Details about a planet’s atmosphere — such as its composition, structure and energy balance — can give clues to its formation and early evolution.

Probes and modules are able to gather data from their target systems by using cameras that can detect visible and infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, Benedict said.

“Cassini did some imaging of Saturn’s moon, Titan, in near-infrared (light) since that could see below the methane haze that covers (it),” said Lara Eakins, program coordinator of UT’s department of astronomy.

The technology that drove Cassini, although extremely crucial, was not as advanced as people may think, Benedict said.

“Computer technology is always five to ten years ahead of what is on a spacecraft,” Benedict said. “My iPhone has many times the computing power of what was on Cassini.”

Even with its outdated technology, Cassini managed to show one of the most Earth-like worlds ever encountered through its exploration of Titan, according to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory website. It also acted as a time machine, making it possible to see physical processes that may have shaped the solar system.

Before executing its final death dive, Cassini underwent a series of dives in between Saturn’s rings as part of its “Grand Finale.” Although risky, this allowed for a close-up study of inner ring space, Trafton said. Because of the chance that Cassini could have been destroyed or damaged by a ring body, it was too risky to do this earlier in the mission.

“(Cassini) was … a long and successful mission that was going out in a blaze of glory,” Eakins said.