According to national opioid statistics, it would appear that Texas does not have a severe opioid abuse problem relative to the rest of the nation. Experts say the data is dangerously misleading, however.

“Unfortunately, that (trend) is a direct result of bad data collection,” said Mark Kinzly, co-founder of the Texas Overdose Naloxone Initiative. “Out of 254 counties in the state of Texas, the (Center for Disease Control and Prevention) will only report on nine of those counties because of how the data is reported.”

According to the Foundation for AIDS Research, the death rate per 100,000 people from opioid overdoses in Texas is barely over half that of the U.S.’s rate. This foundation studies opioid abuse because needle sharing is a common route of HIV transmission.

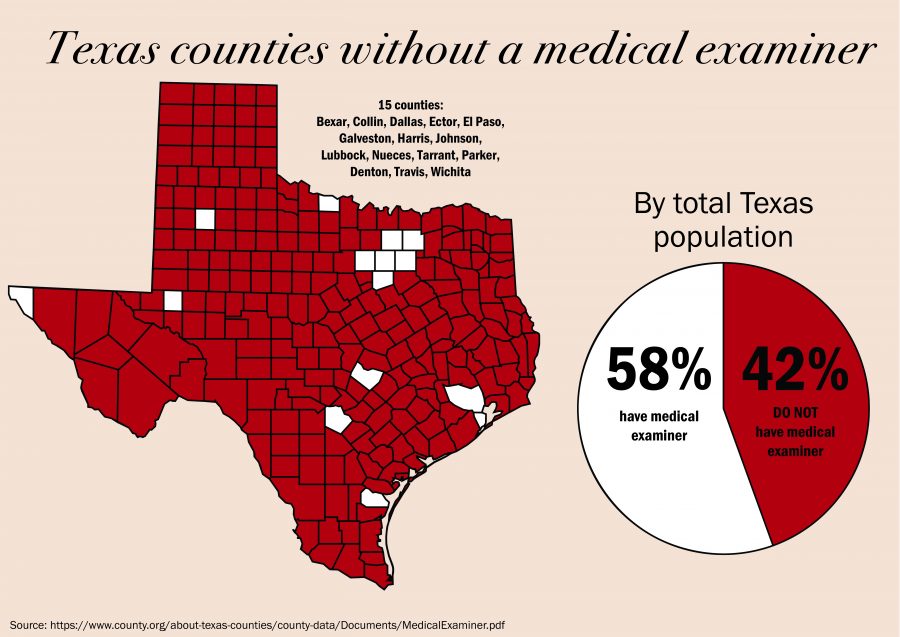

But, Kinzly said, this is because only 15 out of 254 counties — including Travis county — in Texas have a medical examiner’s office to perform autopsies on the deceased.

Only these 15 are mandated by state law to have medical professionals sign death certificates because they have a population of more than one million people. The other 239 counties allow an often non-medically trained justice of the peace, who oversees court functions, decide whether a body needs an autopsy. This can lead to underreporting of overdose deaths if the justice of the piece inaccurately reports the cause of death.

Social work professor Lori Holleran Steiker, who has researched the opioid epidemic, said letting justices of the peace sign death certificates presents a serious problem with monitoring the opioid epidemic in rural areas.

“To the untrained eye, an opioid overdose looks like respiratory failure,” Kinzly said.

This leads to what Holleran Steiker, Kinzly and Operation Naloxone director Lucas Hill feel is a grave underreporting of opioid overdoses in rural areas, because they believe justices of the peace are unable to differentiate between causes of respiratory failure.

Essentially, this issue is causing what they see as a serious disparity between the statistical appearance of the epidemic in the state and what they are actually seeing on the ground.

There are several other factors that point to the severity of the opioid crisis in Texas, Kinzly said. Texas has four out of the top five cities for prescription painkiller abuse in the nation, and the state is second in the U.S. in terms of health care costs associated with opioid abuse.

Hill, Kinzly and Holleran Steiker all say the most critical component for fighting the epidemic is harm reduction, which includes connection to medical treatment for drug abuse and administration of the life-saving drug naloxone, which can often reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, Hill said.

“What we are doing is critical, but on some days feels like a drop in the bucket compared to what needs to be done,” Holleran Steiker said.

Naloxone is now carried by most first responders, such as police officers, paramedics and fire fighters. Now, Hill said Operation Naloxone is looking at nontraditional first responders, such as baristas and librarians, who might encounter an overdose in a public bathroom.

“It’s not uncommon for a barista or a librarian to encounter a person who has overdosed when they go to clean a bathroom,” Hill said. “We need to train them … to respond with naloxone, and we need to get naloxone into public places.”

Holleran Steiker said she is glad the opioid epidemic is finally getting increased attention from all levels of government, but said one of the biggest issues the U.S. still faces is a stigma about opioid abuse.

“A murder gets all the attention nationally, but this — because of the stigma — people stay very private about it,” Holleran Steiker said. “I understand (why), but it’s hard to keep it at the level of awareness that it needs to be.”