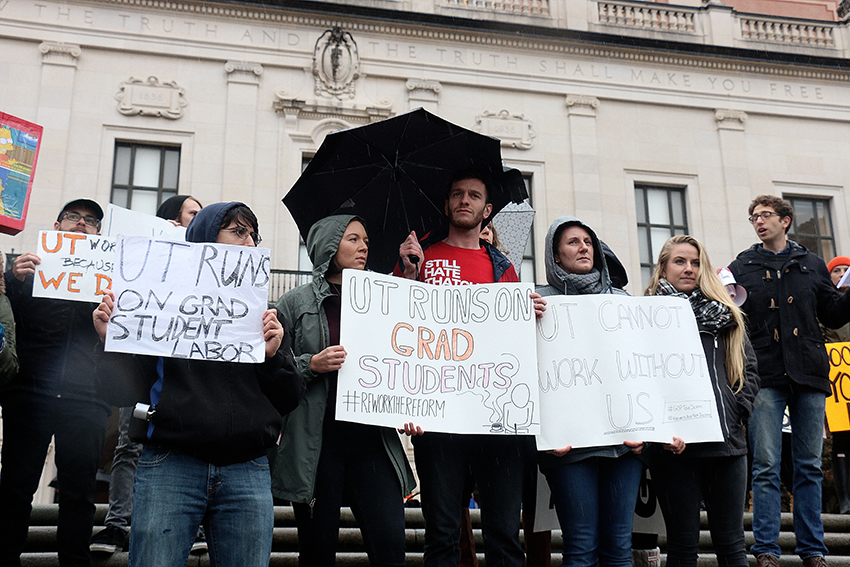

Graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin are writing machine-learning algorithms that will program artificial intelligence. They are helping to develop more effective ways of assessing and treating cancer. They are teaching future CEOs how to write and how to implement ethical business practices.

This is only a short list of the ways UT’s graduate students — and graduate students across the country — support and produce knowledge and innovation that might someday benefit society. Additionally, there is plenty of evidence to support the fact that higher levels of education equal lower levels of unemployment, which means a better economy.

Graduate students are a vital workforce provided with the support to perform painstaking research (and they are usually required to teach while doing so). While the private sector employs researchers who are paid to solve complex problems, research universities are set up to guide their graduate students as they work on a singular project that is the culmination of years of intense study and focus.

Yet with the introduction of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, versions of which were passed by both the House of Representatives and Senate earlier this month, the future of graduate education, and by extension, the future of innovation, research and knowledge, is facing a serious threat.

In order to benefit large corporations and wealthy donors, the bill is projected to add about $1.5 trillion to the deficit over the next 10 years, while negatively targeting the future of education, in addition to women’s health and the environment. The version passed in the House of Representatives includes provisions that would transform graduate tuition waivers into taxable income and would abolish the deduction for student loans. While these provisions were not included in the Senate version, the two bills still need to be reconciled. If the House provisions make it into the final version, graduate students will be unduly punished.

Under the current House proposal, the University of Texas Graduate School estimates that graduate students could see between a 100 and 400 percent increase in their taxes in the next year. Tuition waivers — in the range of $10,000 per year at UT — would be treated like income and taxed. If students have to take out loans to pay these taxes, they may not be able to deduct the interest on those loans from their taxes, furthering the burden of continuing education.

This bill would be devastating to graduate students — some of whom support families — whose stipends are often only $20,000 per year or less. This places graduate students firmly at and below the poverty line. In addition to teaching and research, many take on extra jobs and still need to take out loans just to make ends meet.

Although universities have a responsibility to their graduate students, such as granting waivers to cover tuition costs (and even this is an antiquated way of dealing with graduate student labor), this does not negate the fact that the bill undeniably targets higher education and its intellectual labor instead of recognizing its importance to the economy.

The legislation takes aim especially at graduate students who do not come from privileged backgrounds. Graduate education already disproportionately supports students who can afford to take a financial hit, whether that is by taking out loans or receiving financial support from family. Not all graduate students have this luxury, and for students who are not independently wealthy, the extra tax burden could mean the end of their education.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act exhibits a fierce contempt for intellectualism and the knowledge production that is crucial to America’s workforce and the vitality of its citizens.

Welsh is an English Ph.D. candidate.