On Jan. 15, The New York Times published an opinion piece by Staff Editor Bari Weiss on the recent allegations of sexual misconduct by a woman going by the name “Grace” against comedian Aziz Ansari titled “Aziz Ansari is Guilty. Of Not Being a Mind Reader” which opens with Weiss declaring, “I’m apparently the victim of sexual assault. And if you’re a sexually active woman in the 21st century, chances are that you are, too.” Many readers were relieved to discover that they’re not rapists and that their identification with Ansari is not necessarily damning. But we should all stop to consider what the Ansari story could tell us about our own sexual lives.

Revisiting Grace’s story, originally published on babe.net, we can find instances where Ansari repeatedly ignored cues and persisted in coercing Grace into sex that should not be ignored or glossed over by readers and critics, especially if they are sexually active. After leaving a restaurant and going back to Ansari’s apartment, Grace says that she became uncomfortable with how things were going but carried on. Grace’s description of her feelings during the encounter are chilling: “Most of my discomfort was expressed in me pulling away and mumbling. I know that my hand stopped moving at some points. I stopped moving my lips and turned cold.” All of these cues were ignored by Ansari.

Any of these cues, on their own, might appear minor or of little importance. But when considered together, or observed over the course of an intimate night, any responsible adult can trace a pattern. Grace did not want to have sex with Ansari, something Ansari should have known despite not being a “mind reader,” and these nonverbal cues are as important to understand and act upon as verbal cues are in forming healthy sexual relationships.

It’s important for sexually active students at UT to understand the University’s policy regarding sexual consent. The UT Counseling and Mental Health Center has a webpage which describes consent to sexual activity as an “enthusiastic, mutual agreement that can be revoked at any time for any reason,” as a “conversation that requires consciousness and clarity.” The University’s rules and guidelines about consent provide us with the tools to practice sex safely and without coercion. Verbal ambiguity and “mixed signals” do not constitute consent. Consent to sex is given verbally and repeatedly during the encounter. Many of us were not taught these rules as children by our parents or our sexual education classes, and some of us may have even been sexually active before understanding these rules.

So now that we know what constitutes consent in sex, we should all take a moment to reflect on our relationships and ask ourselves some difficult and uncomfortable questions about our own relationships, past and present. The fear of this sort of reflection is that we may begin to realize that we have, in the past, been irresponsible with our partners. We may realize that we coerced them into having sex even when we should have known (or even worse, did know) that they were not in the mood.

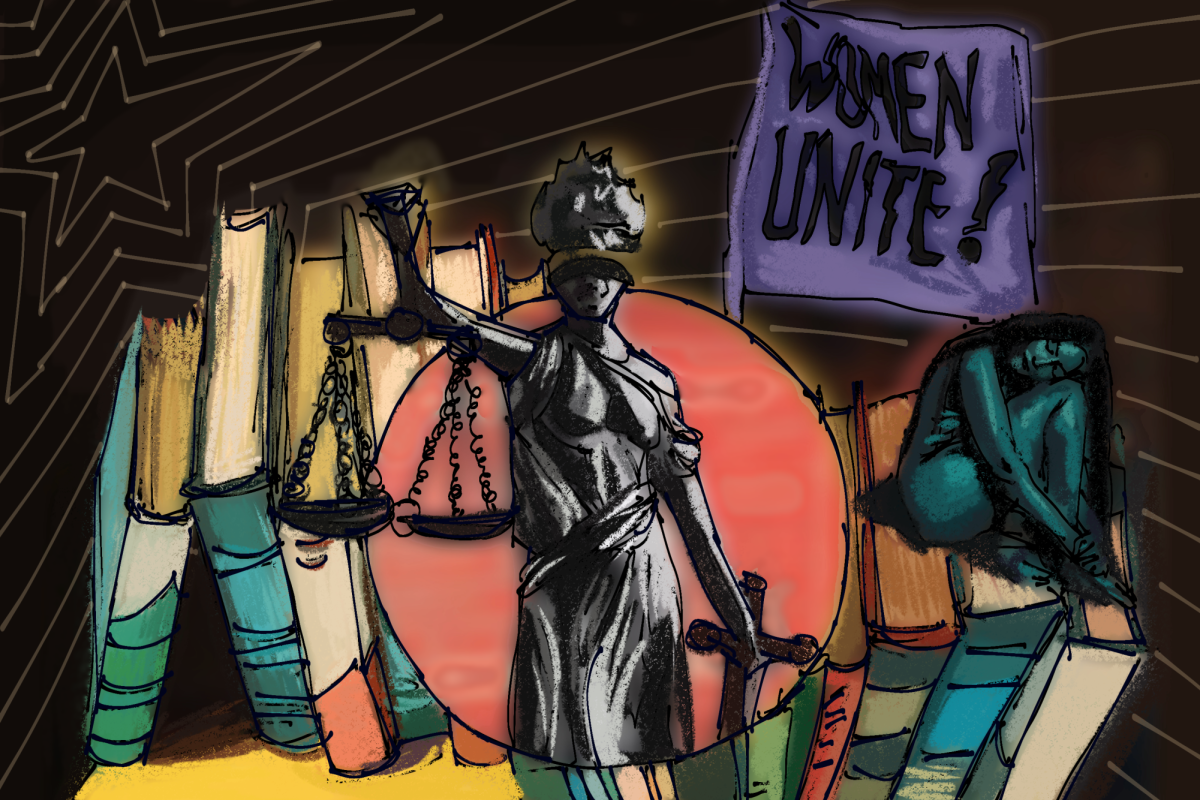

The #MeToo movement, an ongoing movement to combat sexual violence, assault and harassment, doesn’t end with the Ansari story, and it doesn’t stop short of it. Rather, it should begin with our own individual recognition of the sexual trespasses and instances of misconduct that we, ourselves, may have committed against our partners. If we all took amoment to reflect on events in past relationships where we may have been coercive or persistent — rather than outright violent — or cases where we ignored visual and nonverbal cues — rather than ignoring verbal cues — we would be taking the steps to create a safer community on campus and in our city.

DePriest is a communications junior.