As a woman employment lawyer, I view the Me Too movement through that lens. Many of my female colleagues say it would be easier to count the women who have not experienced workplace harassment instead of the other way around, which should cause employers to sit up and take stock. While conducting anti-harassment training sessions, it’s become clear to me there are many who haven’t yet had their “aha” moment on this subject.

In 1991, Anita Hill accused her former boss of workplace harassment. It was newsworthy because the allegation surfaced during U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings and her harasser, Clarence Thomas, was the head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission when the acts occurred. The EEOC is the federal agency charged with enforcing the law, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits workplace harassment. Awkward. The EEOC documented a 53 percent uptick in the number of sexual harassment claims filed the following year. Was there more misconduct? Probably not. It’s more likely there was a growing awareness that the sophomoric behavior alleged by Ms. Hill was more than rudeness, crudeness or “your mama did not raise you right.” If it happened as she said, what he did was a violation of her civil rights, for which there is a remedy. I suspect many women spun through their mental Rolodexes and did not have to search very far to find they too had experienced sexual harassment.

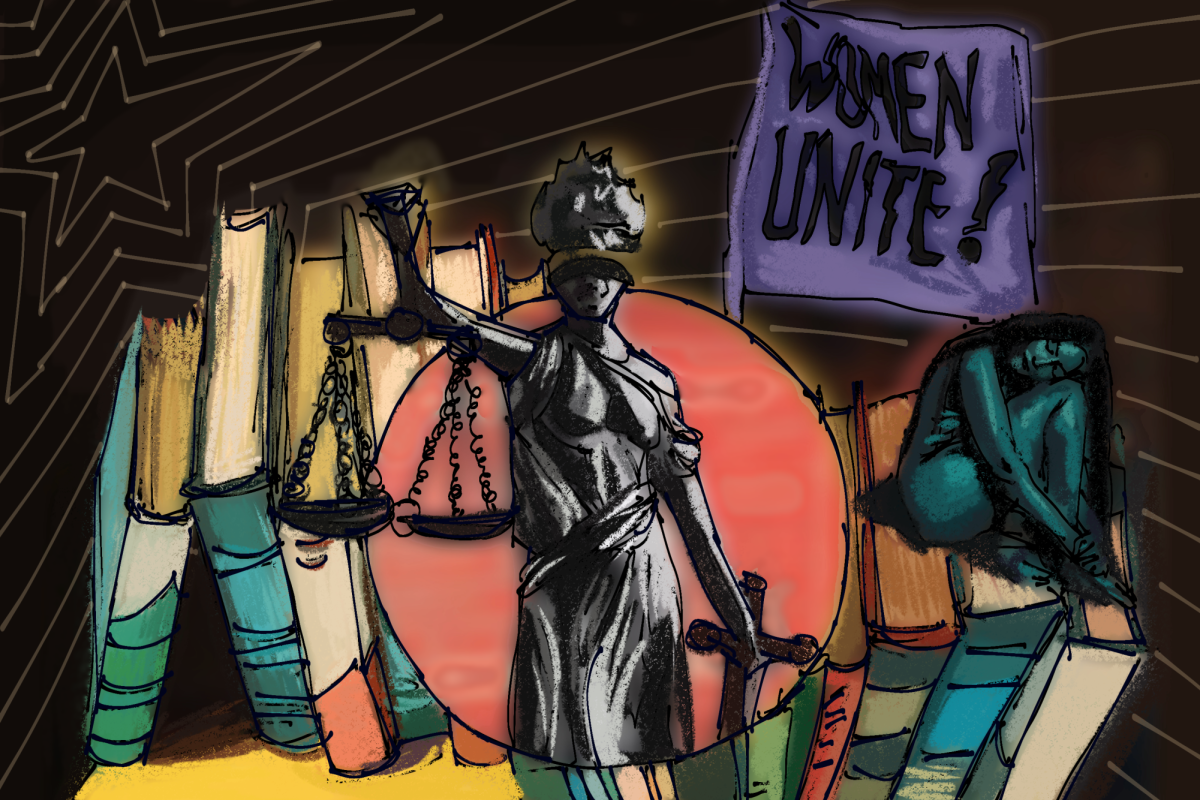

Fast forward to today. We are experiencing another moment of introspection caused by not one man’s misdeeds, but many. This time, the effect is magnified by the sheer number of reports and how far some of the mightiest have fallen. Many are hopeful that this time, there will be a tangible and lasting change which improves workplaces for women and men. The Me Too movement has a growing legal fund to help those who opt for litigation to seek redress, but there are other ways to facilitate positive change in our workplaces:

Policy Make it a condition of continued employment that employees avoid harassing conduct which is based on a person’s gender, race, color, national origin, religion, age or disability. Aggie jokes are still OK.

Recourse Have an accessible complaint procedure and more than one person to talk to. Never require the complainant to begin by reporting to her supervisor first. The supervisor might be the problem.

Investigation Not every complaint will require a lengthy investigation, but every complaint must be heard, acknowledged and looked into. It takes guts to speak up and harassment claims are grossly under-reported. What may appear at first glance to be trivial could be the tip of an iceberg. Pay heed.

Response A first-time and minor offense needs course correction via counseling. A serious offense or repeat offender is going to be shown the door. There is a lot of room between those extremes to craft the proper response.

Education Several states mandate anti-harassment training in workplaces. The U.S. Supreme Court created an affirmative defense against claims of harassment by a supervisor, but its availability is conditioned upon the employer’s reasonable efforts to prevent harassment, which includes conducting training.

I’ve seen the light bulb go off during training sessions when attendees learn, from the trainer and from each other, what types of behaviors cross the line and the consequences for crossing it. And I’ve seen their cold sweat when learning that “I was joking” is not a defense. It’s easy to cross a line, if you don’t know where the line is.

Aha, indeed.

Mross is a labor and employment attorney at Munck Wilson Mandala LLP.