Recently, The Washington Monthly scrutinized UT-Austin’s endowment spending during the tenures of Chancellors Francisco Cigarroa and Bill McRaven.

I was horrified to learn that UT spent so much money on grand, ineffective initiatives. For instance, it dedicated $75 million towards a “startup” called the Institution for Transformational Learning, whose digitization efforts have largely flopped. UT bought hundreds of acres of land in Houston for $215 million, but had no specific plan on how to develop it. The University was eventually pressured to sell the land.

Meanwhile, only $38 million of that endowment money last year went towards student financial aid ($3 million to undergraduates). Legally, nearly $300 million of that endowment could be used for anything: With that money, UT-Austin could have provided free tuition for all of its undergraduates.

While there is some value in UT’s efforts to boost its prestige (and presumably its college rankings) and the success of one of those projects could have somewhat offset all the other failures, it is clear that the University is not prioritizing its students.

UT enrolls just 6 percent of its class from families in the bottom 20 percent in income — a middling result among other publicly selective colleges (where such practices have become normalized), but 129th out of 145th in Texas. Given Texas’s high 2017 poverty rate of 15.6 percent and distressing child poverty rate of 22.2 percent, UT really isn’t adequately serving the state either.

UT could do so much more. It has the ability to give students of modest means free rides in college and tuition breaks for the middle class. It could invest in long-term relationships with poorer communities and partner with high schools to ensure they get adequate college application advice. It could reduce class sizes, something programs like BHP have long enjoyed. It could provide dedicated mentors or tutors for struggling students at risk of graduating late or dropping out. It could expand mental health services to better detect and rehabilitate students going through crisis. It could increase the number of advisers to reduce wait-times for students in need of academic advice. It could raise adjunct pay and increase research resources for current professors, instead of engaging in zero-sum recruiting of “star professors.” It could crack down on the $143 million in administrative bloat spent last academic year, quadruple the figure in 2011.

UT’s behavior makes me skittish about making future donations. While I want to contribute to all those programs mentioned above, I now feel that giving implicitly condones what has been going on.

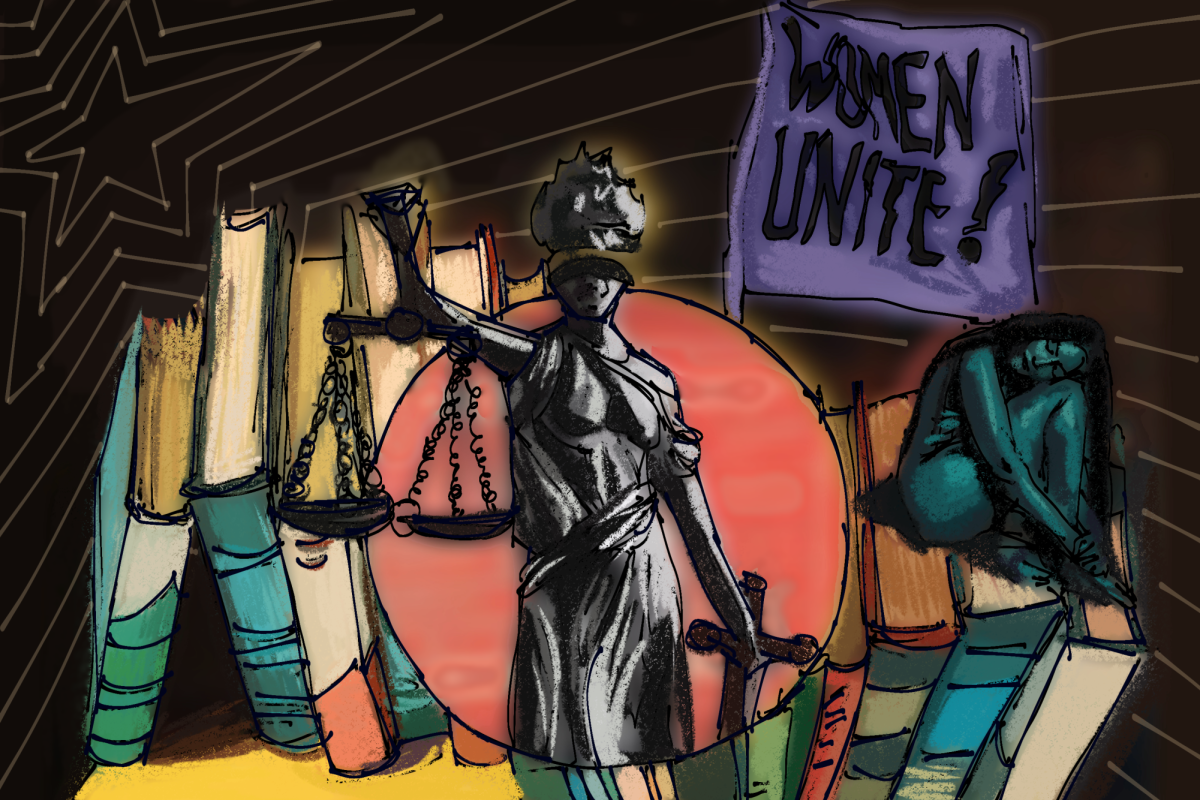

I encourage students, alumni and faculty alike to voice their displeasure at UT’s misappropriations. Please share your stories about financial or academic difficulties during college. Organize rallies and town halls on campus explaining the University’s skewed priorities.

For administrators, the first step would be increased transparency and accountability. Email reports to students and faculty detailing endowment spending at a glance, along with itemized budgets. Provide robust business justifications for your appropropriation decisions, including 10-year financial estimates. Invite public comment on such spending decisions at scheduled forums on campus to invite engagement.

The University’s commitment towards forward-looking initiatives is admirable. However, these decisions should not be top-down, insufficiently publicized and inadequately vetted affairs: They should receive input and broad support from students and faculty.

With Admiral McRaven’s upcoming resignation in May, I sincerely hope that our next chancellor has the correct vision.

Zhang is a BHP/MIS major from Plano, Texas. He graduated in May 2016.