Sixty-eight years have passed since the first black student stepped foot on the 40 Acres. Despite some victories throughout the years, the lack of black representation in the student and faculty population still remains an issue at UT.

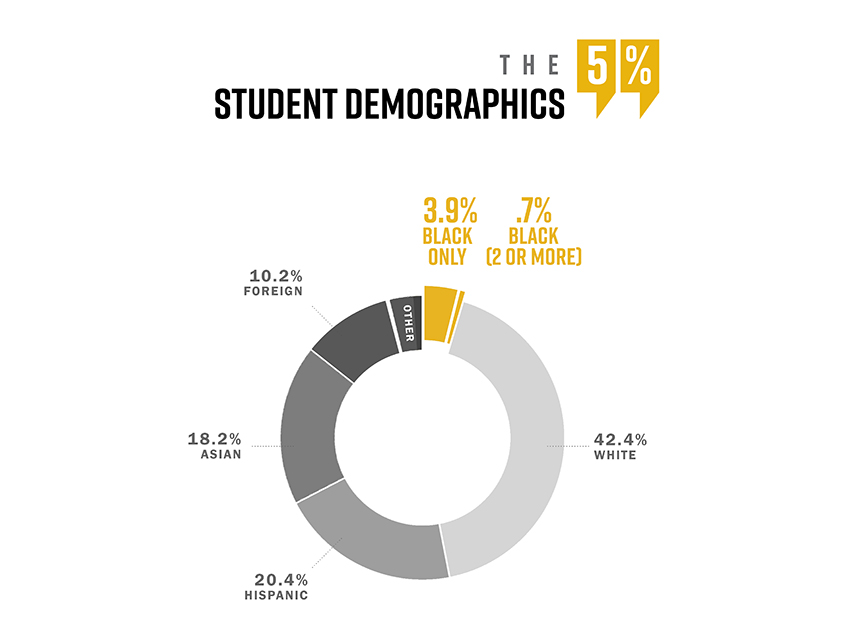

Today, in a sea of more than 51,000 students, fewer than 2,400 students identify as black. According to fall 2017 data, the black student population was only 4.6 percent of the total student body, while the black population in the United States makes up about 13 percent.

Within the black population demographics have shifted over the years. In the fall of 2008, there were 2,192 students who identified as black only and in the fall of 2017, nine years later, there were 1,990. In contrast, the population of students who identify as being black mixed with two or more races has increased from 99 students in fall 2010 to 383 in fall 2017.

Leonard Moore, interim vice president for UT’s Division for Diversity and Community Engagement, said there are many factors why the black student population has remained stagnant for so long.

“Black kids in Texas have a lot of options, from HBCUs, public colleges and even private HBCUs,” Moore said.

Moore said for the last couple of years, the University has been making an effort to increase the enrollment of students of color. Last fall, the University saw the largest incoming class of black students ever at five percent, Moore said.

“You have to have partnerships across the University,” Moore said. “Admissions can’t do it alone. The Division for Diversity and Community Engagement can’t do (it) alone. Everyone has to work together, including the different colleges and schools, to come up with better recruiting strategies.”

Moore said the University has to be proactive in order to admit a class that reflects the nation’s demographics. Despite receiving an astounding number of applications every year, Moore said recruitment is still necessary.

“I think most people just don’t understand the black experience, and it’s not their fault,” Moore said. “I am amazed at how separate our worlds are.”

The lack of black representation is also an issue for faculty. Black faculty make up only 4.1 percent. Out of 3,162 faculty members, only 129 are black. The Jackson School of Geosciences and the School of Information reported having no black faculty members as of fall 2017.

The National Association of Black Journalists is partnering with The Daily Texan this semester for a series featuring black students, faculty and alumni to share their experiences about being part of a community that comprises less than five percent of the total campus.

LAW SCHOOL:

In 1946, Heman Marion Sweatt applied for UT Law School and was denied admission because he was black. However, Sweatt did not take no for an answer. With help from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Sweatt took action against the University in the 1950 Supreme Court case, Sweatt v. Painter. At the time, the president of the University was Theophilus Painter. This landmark court decision successfully challenged the “separate but equal” clause that was established in 1896 by the Plessy v. Ferguson case, which legally upheld segregation as long as African-Americans had their own “separate but equal” facilities. After the success of the Sweatt v. Painter case, Sweatt was admitted to UT Law, becoming one of the first black students on campus and paving the way for future African-American Longhorns. His case also influenced Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which ended segregation in public schools.

UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOL:

In 1956, the first black undergraduate students were able to enroll at UT. Today they are known as the Precursors.

KINSOLVING DORM:

In 1961, black UT sophomore Sherryl Griffin staged a sit-in at Kinsolving Residence Hall to protest segregation on campus. At the time, black female students were only permitted to live in Whitis Dormitory or Almetris Co-op. After the sit-in, Griffin filed a lawsuit against the University that eventually led to residential integration, which was announced by the Board of Regents on May 16, 1964.

UNION BUILDING:

On March 9, 1962, Martin Luther King Jr. visited the 40 Acres to give a speech at the Texas Union building. King gave his speech, “Civil Liberties and Social Action,” to a full room of 1,200 people. King urged for nonviolent protests to fight for equality. In 1962, of 20,000 students on campus, only about 200 were black.

CIVIL ENGINEERING BUILDING:

Ervin Sewell Perry was the first black professor at UT. In the fall of 1964, Perry was named assistant professor of civil engineering, which he remained teaching until his death in 1970. Perry received his Master’s degree from UT in 1961 and his doctorate in civil engineering from UT in 1964. Prior to his death, he was named to receive the first “Young Engineer of the Year” award from the National Society of Professional Engineers.

SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK:

In 1993, Barbara White was appointed dean of the School of Social Work, becoming the first black UT dean. Under White’s leadership, the school doubled its enrollment and established a distinguished faculty. In 2011, White stepped down from the position. She is the former president of the National Association of Social Workers, an organization with 120,000 members.

DARRELL K ROYAL FOOTBALL STADIUM:

Henry Reeves, a trainer, doctor and manager, was the first black person to work with the UT football. He worked with the team from 1875 to 1915, and was referred to as Doc Henry. He was not allowed to eat with or room with the players. After his death, he was elected to the Longhorn Hall of Fame.

Although UT athletics were opened to black athletes in 1963, there were no black football players until 1970. Darrell K. Royal, head football coach from 1957 to 1976, delayed integration of the football team for several years. Black UT students often protested at football games, demanding the inclusion of black football players on the team.

In 1970, Julius Whittier was the first black person to receive a UT football scholarship, and thus the first black UT football player ever to play varsity. In 1973, Roosevelt Leaks became the University’s first black All-American. In 1977, Earl Campbell became the first UT student, white or black, to win the Heisman Trophy.

In 2014, Charlie Strong was hired as the head football coach, becoming the first black head coach of any men’s sport at UT. In 2016, Strong was fired from UT and is currently the head coach at the University of South Florida.

UT TRACK STADIUM:

The first black athlete ever at UT was track runner James Means in 1963, a student from an Austin high school.

FRANK ERWIN CENTER- BASKETBALL COURT:

In April of 2015, Shaka Smart became the 24th head coach of the basketball team and first black head coach of the basketball program.In fall of 1967, Sam Bradley became the first black UT basketball player.

DUREN RESIDENCE HALL:

In 2007, this residence hall was named after Almetris “Mama” Marsh Duren, who played a crucial role in helping black UT students from 1958 to 1981. She served as a mentor, counselor and adviser to inspire young people of color. She served as dorm mother for the first dorm open to black students.

LIBERAL ARTS BUILDING:

In 2010, under the direction of Edmund T. Gordon, the African and African Diaspora Studies Department was established. In 2014, it became the first program in the South to offer Ph.D. degrees in Black Studies. Today, dozens of AFR classes are offered every semester, offering undergraduate and graduate degrees in the program.

MALCOLM X LOUNGE (IN JESTER):

In 1995, students petitioned to the UT president for an area for black students to gather. In 1995, the Malcolm X Lounge was opened in Jester Center as a safe haven for black students. Today, the lounge serves as a space for studying, meetings and social gatherings.

PRESIDENT’S OFFICE (TOWER)

Since the University’s first president in 1895, there have been no black presidents. Over the last 123 years there has been only one woman UT president, Lorene Lane Rogers (1974-1975 ad interim, 1975-1979). All other UT presidents have been white males.

Jade Fabello and Lacey Grace contributed to this reporting.