Students often question how the University of Texas’ $31 billion endowment — the second largest in the country — is spent, which is often unclear.

A common student misconception depicts UT sitting on a giant pile of money they refuse to spend. The Permanent University Fund, which is shared with Texas A&M, supports part of the school’s annual operating budget, and after a decade of especially good investment returns, funnels into a “special distribution” that is now being used to greatly expand tuition assistance for low-income undergraduate students.

The UT System’s endowment also supports nearly 20 times as many students as Yale, whose endowment hovers close to $30 billion. On a per-student basis, UT isn’t even the richest school in the state.

“Rice and Texas A&M have us beat,” UT spokesperson J.B. Bird said.

However, UT still has a lot of money.

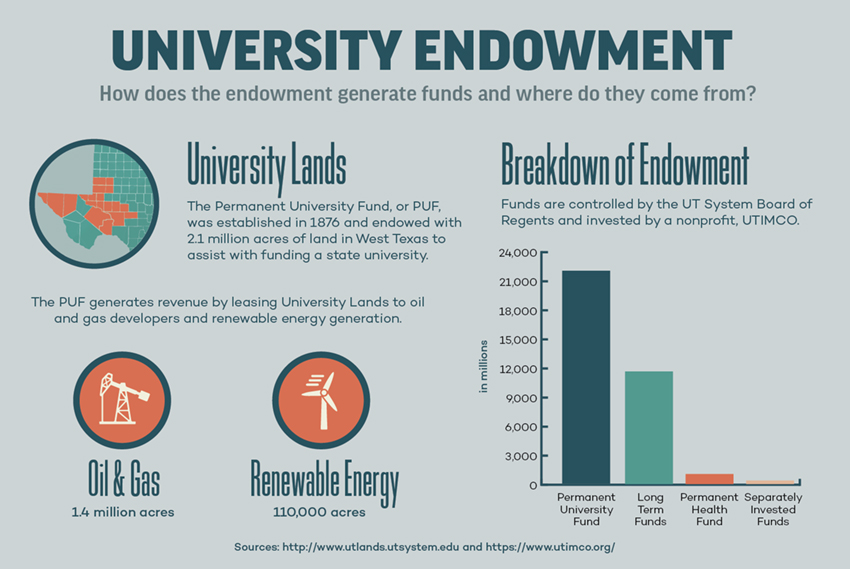

The endowment funds are controlled by the UT System Board of Regents and invested by an adjacent nonprofit, the University of Texas/Texas A&M Investment Management Company, or UTIMCO. UT draws from the returns of those investments annually.

Finance professor Keith Brown said the purpose of a university endowment is to ensure both current and future students are financially supported. The endowment must also keep pace with inflation to support students as the economy changes.

“Humans have an expiration date, but the University of Texas doesn’t,” Brown said.

The Permanent University Fund, or PUF, makes up the most substantial part of the funds generally referred to as “the endowment.”

The PUF, worth about $22.6 billion, generates revenue by leasing 2.1 million acres of land in West Texas. Mark Houser, CEO of University Lands, said 1.4 million acres of it is leased to oil and gas developers and about 110,000 acres are leased to renewable energy generation such as solar and wind. The income collected from the land is then invested by UTIMCO.

Compared with schools such as Yale or Harvard, funding from the University of Texas’ endowment makes up a relatively small portion of its operating budget. For the 2018-19 fiscal year, only 12% of UT Austin’s budget came from endowment funds.

Thirty-five percent of Harvard’s and 34% of Yale’s budgets came from endowment funds. There are two reasons for the substantial difference, Brown said. Unlike Harvard and Yale, UT’s endowment supports current and future students in the entire 14-institution system, and UT is publicly funded and typically gets another 12% of its funding from the state budget.

Beyond that, the state stipulates how money from the PUF can and can’t be spent. The Available University Fund is first used to pay off the UT System’s debt, and then the rest is allocated to UT for expenses such as new construction, salaries, scholarships and library support.

However, the state does not allow the Available University Fund to be used for operational expenses for the other UT System institutions.

The rules don’t stop there.

“The constitution expressly prohibits the use of PUF bond proceeds for student housing, intercollegiate athletics or auxiliary enterprises,” said Melissa Loe, UT-Austin’s director of communications, Financial and Administrative Services, in an email. “The AUF is appropriated by the legislature and is subject to details, limits and restrictions imposed by appropriation.”

Traditionally, these have been the reasons students don’t really see this money. Now, they are starting to in a much more concrete way.

In early July, the Board of Regents called a special meeting and approved a one-time $250 million supplemental distribution from the Permanent University Fund to the Available University Fund.

This distribution will establish a separate $160 million endowment to provide tuition assistance for low-income undergraduate students at UT-Austin.

While the Board of Regents makes the final decisions on the use of the PUF and other endowment funds, it is UTIMCO’s jurisdiction to make investment decisions which are later approved by the board. Brown said UTIMCO uses an external management system, which means the actual decisions about which investments are made are contracted out.

“(UTIMCO picks) the people who pick the stocks,” Brown said.

The way UTIMCO has invested funds is outlined in a 100-plus page document that lists all of the securities that UTIMCO holds and all of the investments it has made.

These securities are varied and range from domestic and international holdings in tech companies such as Facebook and Microsoft, renewable energy corporations such as CS Wind, banks such as Bank of America, and oil and gas corporations such as Royal Dutch Shell, commonly known as Shell. The PUF investment portfolio also holds debt securities from Chevron, ExxonMobil, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and more.

But some of the investments are completely hidden from public view.

Brown said companies like UTIMCO take advantage of finance laws allowing them to keep certain investments confidential for competitive purposes.

UT, Harvard, Yale and Stanford all want to have the nation’s largest endowment; it’s a competition, Brown said. As a result, there are investments in the report that are simply labeled “Direct Investment #01-74” with no other details.

“If people know what’s in your portfolio, then they can reverse engineer your strategy,” Brown said.

Many of UTIMCO’s investments are public, however, and the fossil fuel industry makes up the largest portion of it.

Investing in fossil fuels and leasing land for oil and gas operations are practices many students have been critical of.

In 2013, Harvard students called for the university to divest from fossil fuels. In response, Harvard Management Company, UTIMCO’s counterpart at Harvard, hired a vice president for sustainable investing and would later go on to adopt a sustainable investment policy. But it did not divest from fossil fuels completely.

Now, Harvard takes environmental, social and corporate governance factors into consideration when making investment decisions. These factors include energy consumption, employee diversity and nondiscrimination policies. In 2014, Harvard Management Company was also the first university endowment company in the United States to sign the United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment.

UTIMCO does not have a policy parallel to Harvard’s but said it does work with many firms that do consider environmental, social and governance factors in their investments.

“For example, these firms may recognize that by implementing business practices that are environmentally sustainable, they can also improve the profitability and long-term competitiveness of a business,” UTIMCO said in a statement. “By working with these firms, UTIMCO is supporting (environmental, social and governance) initiatives.”

Sustainability studies senior Andrew Jones, who serves as the director of learning for the student organization Sustainable Investment Group, said there should be a greater emphasis on sustainability in funds such as UT’s endowment because it’s being invested on an “infinite time horizon.”

“It will take 1 trillion dollars of sustainably invested capital each year to meet the sustainable development goals by 2030, and it will potentially take more money invested in low-carbon assets each year to prevent a global warming scenario that exceeds two degrees Celsius,” Jones said. “We are talking about a massive shift in the way that financial markets are operating in order to secure the world that we want to live in.”