Elizabeth Warren taught at Texas Law in the 1980s. Here’s what we found in her faculty file.

February 18, 2020

AUSTIN – In the 1980s, before she ran for president or was elected to the United States Senate, Elizabeth Warren was a professor at The University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

Warren’s time in Texas has largely influenced her progressive political identity. As NPR pointed out, much of Warren’s later academic and professional work — and some of her campaign messaging — can be traced back to the bankruptcy research she began while at Texas Law.

But what was professor Warren like? What classes did she teach? How much was her salary? When and why did she leave?

Records obtained by The Daily Texan under a Texas Public Information Act Request show Warren was a respected and well-liked professor who UT was unable to keep on staff amid competitive offers from other institutions.

Here are a few highlights from Warren’s faculty file.

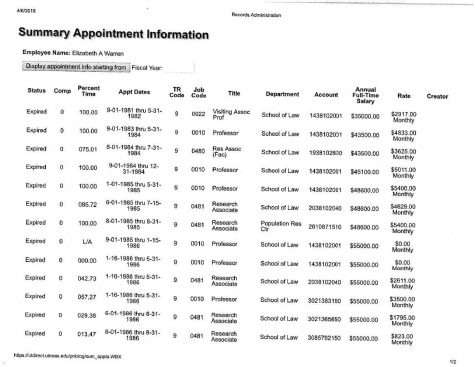

1. Warren was employed by Texas Law for a total of 52 months and 16 days.

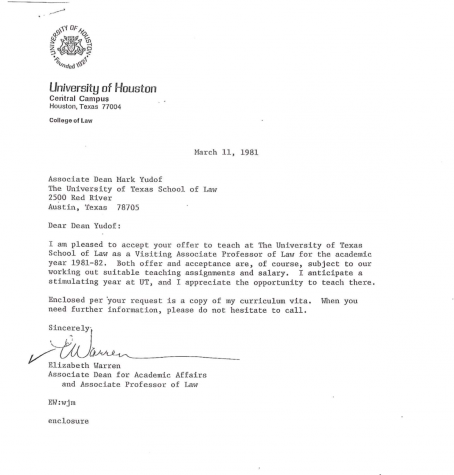

Warren was first hired by UT as a visiting associate professor in 1981 and then as a full professor in 1983.

At the time, she was one of only a handful of women faculty at the School of Law.

In her 1984 annual faculty report, Warren wrote she was the faculty adviser of the Women’s Law Caucus. In her 1986 report, Warren wrote she “organized a conference on interviewing and placement for women and minority students.”

Warren taught Texas Law students during the school year as well as over the summer. At times, she took leaves of absence to teach elsewhere or develop future curriculum. In 1987, Warren left UT to become a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, although she later returned as a research associate and visiting professor. In 1991, Warren taught a summer session course called “Secured Credit” that ran for six consecutive weeks and met for 70 minutes, five days a week.

Warren’s EID was eaw457.

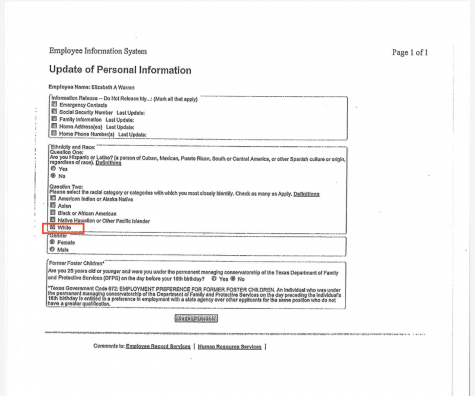

2. Warren identified herself as white on her UT employment paperwork.

Some of Warren’s critics have accused her of falsely claiming Native American ancestry to further her academic and political careers. In May 1986, when she was still a full professor at Texas Law, Warren listed her race as American Indian on a registration card for the State Bar of Texas. But on personal information forms for UT, Warren identified herself as white. She is also listed as white on accounting paperwork from 1981, when she first joined Texas Law.

3. Warren’s starting annual salary was $35,000. Her ending annual salary was $100,000.

As a visiting professor during the 1981-1982 school year, Warren’s annual salary was $35,000. During her first year as a full professor, her annual salary increased to $43,500. By the time she left for Penn in 1987, her annual salary was $61,200. Warren’s final annual salary at UT was $100,000, when she worked as a visiting professor in summer 1991.

4. Warren was a “classroom superstar” who sparked enthusiasm among faculty and students.

In numerous recommendation letters, Warren was praised by colleagues for her bankruptcy research and teaching style.

In 1983, when Warren was being considered for full professorship at UT, professor Teresa Sullivan wrote that she had been initially hesitant about researching bankruptcy law, but Warren helped change her mind.

“From my previous exposure to commercial law, I had concluded that it was an intellectual backwater,” Sullivan wrote to the appointments committee chair. “And in that backwater, the most stagnant pool — I thought — was bankruptcy. The bankruptcy project was Liz Warren’s brainchild. She persuaded Jay and me that such a project was feasible, important and, most importantly, intellectually exciting.”

John Mixon, then a law professor at the University of Houston, called Warren “a classroom superstar.”

“Elizabeth Warren is clearly one of the best law teachers around,” he wrote in a 1983 letter recommending Warren for full professorship. “Her students cover the material, learn it and respect her for making them work. Her enthusiasm for teaching would make even a dull course fascinating.”

In 1986, Warren was recommended for a faculty fellowship by Mark Yudof, dean of UT’s School of Law at the time. In his recommendation letter, Yudof spoke highly of Warren’s rapport with students and the “landmark” bankruptcy study she was working on with Sullivan and professor Jay Westbrook.

“Professor Warren is a superb and popular teacher who draws large numbers of students to her courses,” Yudof wrote.

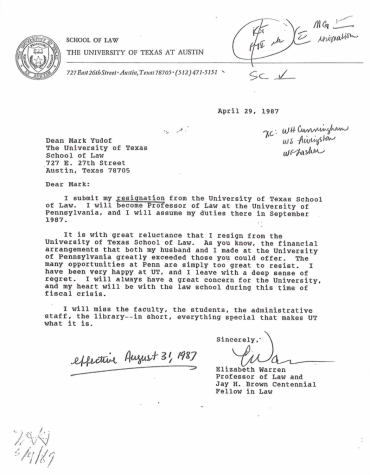

5. Warren left UT in 1987 for a higher-paying position at Penn.

In 1987, Warren left her professorship at UT to become a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania. In the letter of resignation she submitted to Yudof in April 1987, Warren cited “financial arrangements” that she — and her husband — had made with Penn as the main reason for her departure.

“It is with great reluctance that I resign from the University of Texas School of Law,” Warren wrote. “I have been very happy at UT, and I leave with a deep sense of regret. I will always have a great concern for the University, and my heart will be with the law school during this time of fiscal crisis.”

“I will miss the faculty, the students, the administrative staff, the library — in short, everything that makes UT what it is,” she wrote.

6. Before she resigned, UT wanted to offer Warren’s husband a job at the School of Law.

At the time Warren announced her resignation, her husband, Bruce Mann, had also accepted a teaching position at Penn.

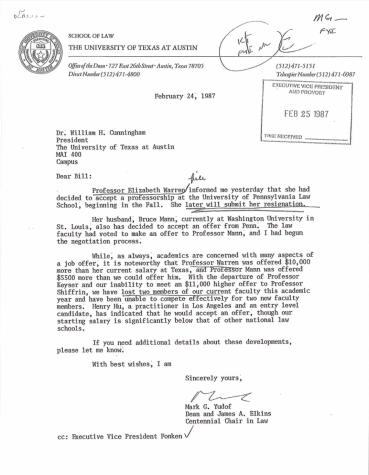

In a letter to UT’s then-president William Cunningham, then-dean Mark Yudof wrote Penn had offered Warren $10,000 more than her current UT salary, and Mann was offered $5,500 more than UT could give him.

“The law faculty had voted to make an offer to professor Mann, and I had begun the negotiation process,” Yudof wrote in theFebruary 1987 letter. “While, as always, academics are concerned with many aspects of a job offer, it is noteworthy that professor Warren was offered $10,000 more than her current salary at Texas, and professor Mann was offered $5,500 more than we could offer him.”

With the departure of Warren and two faculty members in the same academic year, Yudof wrote that the School of Law had been “unable to compete effectively for two new members,” and lamented that “our starting salary is significantly below that of other national law schools.”