Determined to show her children a world beyond their backyard, CeJai said she emphasized the importance of education as a means to serve others.

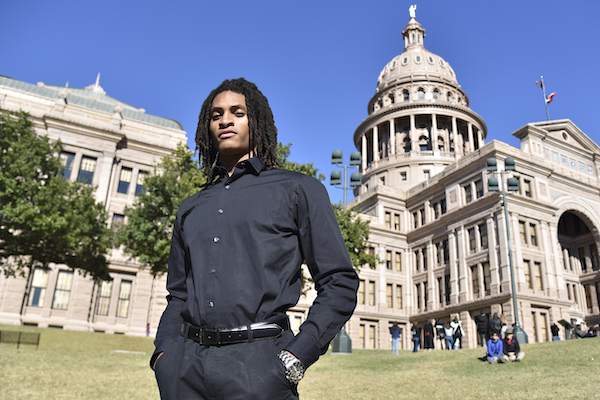

Growing up under his mother’s influence, Chase Moore valued the balance between academics and athletics. At 23, the former defensive back and current graduate student has impacted both the Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium and the Texas State Capitol.

Although he dreamt of one day playing for the NFL, Moore said conversations with his mother about his future always included graduate school.

“You’re more than four quarters,” CeJai would say. “You’re more than a Black man with a ball running into the end zone. Now let’s show the world how much more you are than that.”

As a single mother and her sons’ first coach, CeJai said football saved her family’s life. Moore said she encouraged him and his brother to play the sport and attend an all-boys Catholic school to give them the male mentorship they couldn’t get at home.

“There were times when we struggled,” Moore said. “There were times when answers weren’t there. But she used to always have the mentality that, ‘Although we live in the hood, the hood doesn’t have to live in us.’”

This mentality led Moore to the Texas State Board of Education 15 years later, where he testified on the adoption of a new African American studies course in Texas public schools.

“I don’t want (my children) to have to grow up in circumstances where they think the only way they can make it is through the pressure of athletics,” Moore said. “What about the pressure of reading, the pressure of writing. I want that to be as important.”

Rolling the Dice

After spending his freshman year playing football at College of the Holy Cross, Moore said he left the stability of guaranteed playing time and a full-ride scholarship in 2016 to pursue his dream of playing UT football.

“I don’t want to be one of those people that give advice to their grandchildren and tell them to chase their dreams, but I didn’t chase mine,” Moore said.

Two months later, Moore received a letter of rejection from UT. But after appealing and contacting administration, Moore was accepted into UT and walked onto a football field full of coaches that didn’t know his name.

“More people that come from backgrounds like myself belong here,” Moore said. “We bring something different to the table. There’s some diamonds in the inner city silos that deserve to be in these circumstances too.”

Looking back, Moore said he realizes football was the passport to graduate school, opportunities to study abroad, learning a new language and advocating for educational policy and inner-city youth. He is currently pursuing his Master’s in Educational Leadership and Policy at UT.

Changing a System

Growing up in inner-city Los Angeles, Moore said he struggled to see himself represented in school textbooks and history lessons. Taught that the most important part of his history was slavery, he said he grew up thinking he was ultimately less than others.

“That’s all we ever (were), and that’s all we’ll ever be,” Moore said. “(If) I had educators around my corner telling me that we come from kings, queens, doctors, lawyers and presidents, my disposition toward what I could amount to would have been very different.”

On Nov. 13, Moore testified at the Capitol on the importance and standards of an African American studies course in K-12 classrooms.

“I’m an African American male with dreadlocks who (says) he played football,” Moore said. “But then I’m speaking upon such issues as it relates to education policies and what we can do to change things. It kind of creates a cognitive dissonance (in the eyes of the board).”

While the decision to implement the course has already been made, Moore said many people disagree with the course’s implementation and think it would only benefit African Americans.

Despite some negativity, Kalen McGuire, a studio art senior and Moore’s best friend, said Moore uses his experiences to make a better future for younger generations.

“He teaches through action,” McGuire said. “If he (wants) to speak at 10 juvenile detention centers in two weeks, he’s going to find a way to do it. He’s not waiting for somebody to give him a green light.”

After posting a video of his testimony on Twitter, Moore said the retweets and likes began flooding in within minutes. Currently, Moore’s video on Twitter has over 970,000 views.

Moore said his favorite reaction was from his second grade teacher, who taught him how to read in a system where students typically learn at a slower rate.

“She told me how proud she is and how she saw something in me,” Moore said. “She knew I was going to be part of something greater. When she did (that), she saw a need and she filled a need, which is what I’m doing today.”

Chasing Dreams

Moore said he’s dreamt of shaping educational policy since childhood, but he didn’t think he could have a notable impact this young.

“Being that I have the platform and I come from an inner-city area where I can advocate for change, I figured that it’s my duty,” Moore said. “So there was no hesitation. It was just a matter of when I could do it and where.”

Determined to continually raise awareness about educational policy, Moore said he shares what he learns on social media for people who wouldn’t otherwise have access to that information.

Moore said he has pledged to tweet a weekly video on educational policy. So far, he has covered subjects such as school closures and inhospitable learning environments in inner-city schools.

“I come from an area where most people don’t have the opportunity to engage in academics,” Moore said. “(Student athletes) have grand platforms, and it’s our utility to use it.”