Black student-athletes comprise a majority of Division I football and basketball players, but a discrepancy between the number of white and Black head coaches still exists throughout the college ranks.

Of the 130 schools in the Football Bowl Subdivision, college football’s highest level of competition, only 13 have a Black head football coach, according to the Chicago Tribune. Two Power Five conferences were without a Black basketball head coach at the end of the 2019 season, and head baseball coaches of color are rare outside of historically Black colleges or universities. Texas has had just six Black head coaches across 16 school-sanctioned sports in its 127 years in intercollegiate athletics.

Rodney Page became UT’s first Black coach of any sport in 1973 when Texas hired him to coach the women’s basketball team for its inaugural season. During his three seasons at UT, Page only recalled coaching against other Black coaches when the Longhorns played historically Black colleges and universities.

“When you get into the same level of schools that were in the Southwest Conference, there weren’t any (Black coaches),” Page said. “If you look, you would not find many at a predominantly white institution, a white DI school.”

The scarcity of Black coaches at the Division I level remains prominent over 40 years later due to unconscious biases and a double standard for Black coaches, said Louis Harrison, a professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at UT.

White athletic directors often hire candidates they’re comfortable with — usually other white males — and hold Black coaches to a higher standard, Harrison said.

“Typically, when AD’s look at Black coaches, the Black coach has to be superior,” Harrison said. “They have to have more qualifications than a white coach that they would look at for a similar position.”

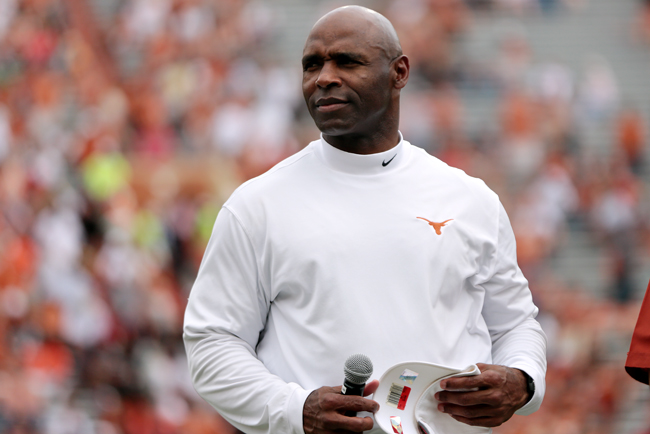

Texas fired Charlie Strong, UT’s first and only Black head football coach, after he failed to deliver a winning season during his tenure from 2014-2016. Some athletes worry Strong’s shortcomings may discourage the University from hiring Black head coaches in the future.

“I do fear that, the way things went with Coach Strong, it would deter UT from hiring another Black football coach,” said Cameron Townsend, a former Texas linebacker who played under Strong in 2016. “It’s kind of like they did it one time just so they can say they did it. Now it’s like, ‘We tried that before, and it didn’t work.’”

Townsend recalled having graduate assistants on staff with only high school playing experience. Limited opportunities for Black people to coach DI football doesn’t make sense in a sport with predominantly Black athletes, Townsend said.

“All these Black football players, and you’re telling me none, or very few, grow up to be qualified coaches?” Townsend said. “If the sport is a majority Black, (how are) the people that teach the sport a majority white?”

UT and other DI schools have made recent strides toward diversity among head coaches. Texas hired or promoted four Black head coaches in the 2010s, a stark contrast to the University that Page said held the reputation of “an orange and white plantation” in the Black community when UT first hired him.

But Page said Texas isn't where it needs to be yet.

“We’re at a moment in American history where what’s coming up is that Black (people) have not received the opportunities that perhaps should have been and should be afforded to them,” Page said. “Although we have made progress, it still can be a battle and a struggle to have an equal and a level playing field.”