On May 8, 1970, thousands of student protesters marched along Guadalupe Street toward the Texas State Capitol. Alongside them, reporters from The Daily Texan were identified by white bands around their sleeves as the journalists and protesters alike carried bags of wet washcloths to protect their faces from tear gas.

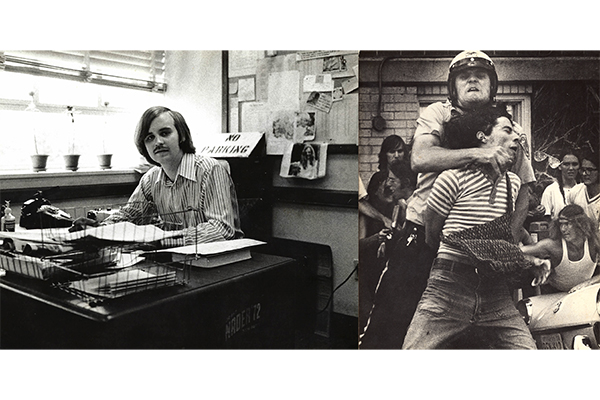

“Here we are going to college,” John Reetz, the Texan’s 1971 managing editor, said. “One evening we’re putting out copies of the paper, and on the other side of the room (our reporters are) ripping sheets into little bitty armbands, writing ‘Press’ on them and getting ready to go out.”

Fifty years later, protests against police brutality have erupted across every state in the United States in response to the police killings of George Floyd and other Black Americans. Although the movement’s purpose is different, Austin’s streets once again serve as the backdrop for protestors calling for change.

Journalists still report on protests today, but 60 Minutes’ “60 in 6” correspondent Wesley Lowery said they face a different set of ethical questions than they did 50 years ago, questions recently brought to the surface by the national protests against racial injustice.

“Everything moves more quickly,” Lowery said. “It's not that there were never photos or interviews of protesters, but it’s that 45 seconds after I’ve taken a photo of someone, the entire world can be seeing it. … By the time they get home, their entire life could be upended.”

In the late 60s and early 70s, long before the days of instant Internet access, anti-war and civil rights protests frequented campus grounds. The anti-war movement, in particular, motivated thousands of students to march for the Vietnam War’s end, pushing back against UT’s controversial regulation of demonstrations.

After 13 unarmed Kent State students were injured and four were fatally shot while protesting the U.S. bombing of Cambodia, Reetz said UT students held a candlelight vigil on the Main Mall to honor the students’ deaths. Four days later, on May 8, 1970, an estimated 20,000 demonstrators made up of largely UT students peacefully marched under threat of the National Guard to protest the tragedy.

For The Daily Texan staffers, covering the campus protests against the Vietnam War meant an endless string of long nights in the newsroom.

Waiting for reporters and photographers to return from covering the protests, Cyndi Krier, former reporter and 1971 alumna, said the paper was regularly sent to print hours after the typical 12:20 a.m. deadline. As the sun rose the next morning, staffers gathered around the printing press to grab a first edition.

To attend protests, students often missed class. O’Lene Stone, former news editor and 1972 alum, said some faculty voluntarily canceled class and most campus academic buildings stood empty.

“I can remember being out on the Main Mall with thousands of students,” Stone said. “We had armed police on top of the buildings along the route to make sure things remained calm. You could hardly walk at times.”

As a reporter, Krier said she joined crowds of protesters to interview students.

“It was almost like a UT football game,” Krier said. “The noise you would feel in the football stadium when people were stamping their feet on the aluminum benches, where you could almost feel the crowd move.”

Reetz, president of alumni organization Friends of The Texan, said although most movements were largely peaceful, some were particularly violent. He said police sometimes used clubs and fired tear gas, most often when students were chased from Capitol grounds after refusing to disperse.

When protests turn violent, journalists today often turn to police accounts for objective truth, said Lowery, who covered the Minneapolis protests. This common practice has raised ethical questions about who controls the narrative of protests.

“Very often, the police play some type of role in (protest) violence,” Lowery said. “And then we turn to the police and have them write the lede of the story. If someone says something behind a microphone, suddenly it must be true. And we know that’s not actually how the world works.”

The Texan’s anti-war protest coverage circulated widely among the student body, but Krier said not everyone approved. The UT System Board of Regents, specifically board chairman Frank Erwin, condemned many opinion stories from the Texan that criticized national policies and the student-led protests themselves.

“I am disturbed because a bunch of dirty nothings can disrupt the workings of a great university in the name of academic freedom,” Erwin said when war protesters interrupted a 1968 event with President Johnson at Gregory Gym.

As one of the only publications readily accessible to students, the Texan was an outlet for controversial dialogue, student speech and a space for national news alongside local events.

"People would turn to the Texan, and that always made me feel good, and even as a fairly young person (it) reinforced my decision that I wanted to be not only a journalist but a newspaper reporter," Stone said.

After the paper went to print each night, the Texan staff would often gather at someone’s apartment for drinks until dawn the next day. It was only then when the somberness of the day’s events became evident in his reporters, Reetz said.

“We were all new to college, new to Austin, new to protests, new to people being killed,” Reetz said. “The emotion of it was certainly there after the paper was out. Everyone felt a sense of being invested in an institution like the Texan that's been around for so long that they wanted to do the right thing.”