UT-Austin researchers identify microbial organism that helps control greenhouse gases

May 7, 2021

UT scientists have discovered a previously unidentified group of microbial organisms that can break down dead matter without releasing greenhouse gases.

In an April paper published in “Nature Communications,” UT scientists identified the Brockarchaeota group of microbes, which were first located in Mexico. Researchers say the organisms help protect the environment because they can break down dead plant matter without releasing methane, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change.

Valerie De Anda, research associate and lead author of the paper, said Brockarchaeota’s ability to recycle carbon without releasing methane gas is vital for Earth’s atmosphere.

“The accumulation of organic carbon in the form of methane, which is a greenhouse gas, is very important,” De Anda said. “(Knowing that) they are using the same substrates as organisms that produce methane but they are not producing methane … this has to be incorporated into climate models to understand the regulation of carbon on the planet.”

Brett Baker, a marine science assistant professor, said in an email that the identification of Brockarchaeota was part of a larger ongoing project in the Guaymas Basin of Mexico.

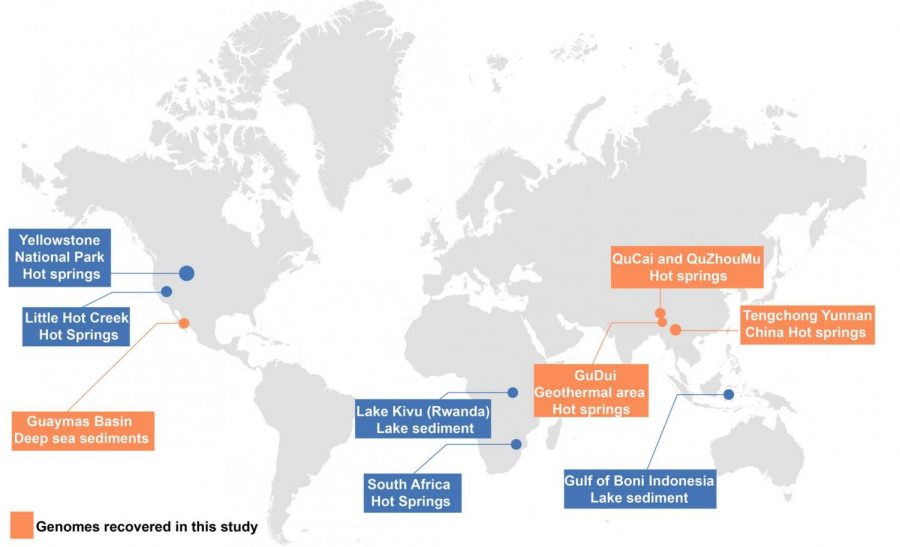

Brockarchaeota have been identified in aquatic environments across the globe. De Anda said two of their genomes were discovered in a mass sequencing of over 500 deep sea microbial genomes by Nina Dombrowski, a former postdoctoral researcher in Baker’s lab.

The identity of these genomes was a mystery until a team of Chinese researchers told De Anda that they possessed similar genomes to samples taken from thermal hot springs in China, De Anda said.

After collaborating with the Chinese scientists, De Anda said they realized the genomes were similar despite being sequenced from different locations.

“We started to analyze them and we found that they were indeed a novel branch within the tree of life,” De Anda said.

Baker said his lab does not intend to continue studying Brockarchaeota but plans to examine microbial communities from similar locations to determine how the new species fits into the ecosystem.

“My best guess is that (Brockarchaeota) will be seen in lots more environments now that we are aware of them, and the ecological roles will be better understood,” Baker said.

De Anda said UT researchers will collaborate with Montana State University to isolate Brockarchaeota from other microorganisms and study their interactions.

“We are characterizing a huge amount of novel diversity and novel branches of the tree of life,” she said.