UT-Austin research shows which memories are right or wrong based on cell firing patterns

June 24, 2021

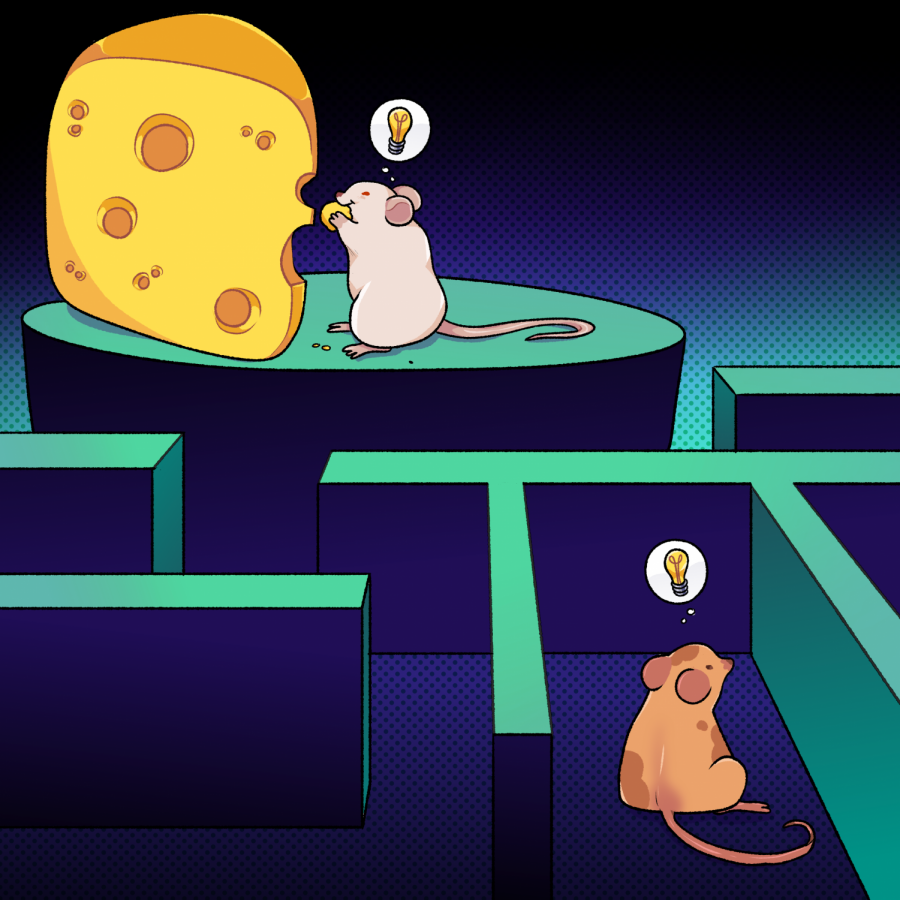

UT-Austin researchers found differences in how correct and incorrect memories are activated in the brain through watching rats in a maze. The study, published June 7, could help researchers understand Alzheimer’s disease.

Chenguang Zheng, an alumnus and author of the study, said the team of researchers wanted to know how memory was encoded, stored, received and activated in someone’s brain.

“Memory is kind of mysterious because sometimes you could not describe a skill which you will not forget at all in your life, or sometimes you could remember some delicious food your grandma made (a) long time ago when you smell some related scent,” Zheng said in an email.

Neuroscience associate professor Laura Colgin said the team implanted a recording electrode into the rats’ hippocampi, a region of the brain responsible for storing memory, to record cells called place cells and the way they activate.

“With (place cells) firing pattern(s), that tells what’s happening there … all of those cells together can code the experience of what’s happening in a particular environment,” Colgin said

Colgin said the team trained the rats to go through a circular track multiple times with food as a reward for finding the goal location marked with tape. The marked location would then be removed and the rats would have to go through the maze and find the goal using their memory, she said.

Colgin said in trials that went correctly, the place cells would activate and fire a sequence of patterns in the rats’ brains. When rats went to the wrong location, they found that cells in their brains fired the same pattern sequence, but much more slowly.

“It was like the cells were getting activated with a delayed start on the error trials, and then they were also getting activated more slowly in the error trials,” Colgin said. “It was more sped up, everything’s happening faster (in) the correct trial.”

Alumnus Ernie Hwaun, who was part of the research team, said rats who remembered the correct location would activate their place cells before starting the trial, showing that the rats were trying to remember the location. This wasn’t seen in rats who arrived in an incorrect location, he said.

“It’s as if your hippocampus is rehearsing what’s going on in the past,” Hwaun said.

Colgin said the team’s next step is to take the recording techniques from the rat model and see how Alzheimer’s affects how the brain stores and retrieves memories.

“One theory is that memories are getting stored but there’s a problem with retrieving them, and so we could look at that with these kinds of techniques,” Colgin said. “As the animals are having this experience, is the brain developing these representations of what they’re doing, but then something is going wrong later where they can’t read out the sequences?”