Computer simulations could predict language rehabilitation outcomes in stroke survivors

June 28, 2021

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared as part of the June 22 flipbook.

When bilingual people lose the ability to speak due to brain damage from a stroke or head injury, deciding which language will be easier to relearn can be a guessing game. Now, UT researchers can better determine which language people will recover more easily.

UT and Boston University researchers created a brain simulation that predicts rehabilitation outcomes for bilingual patients experiencing language loss due to aphasia, according to their study published May 18.

“Once you understand their language background and how impaired they are, the model can predict how (many) improvements the person is going to make if they received therapy,” said Swathi Kiran, director of Boston University’s Aphasia Research Laboratory and lead author of the study.

Kiran said her team assessed the patient’s relationship with each language and determined the severity of communication loss based on the patients’ history.

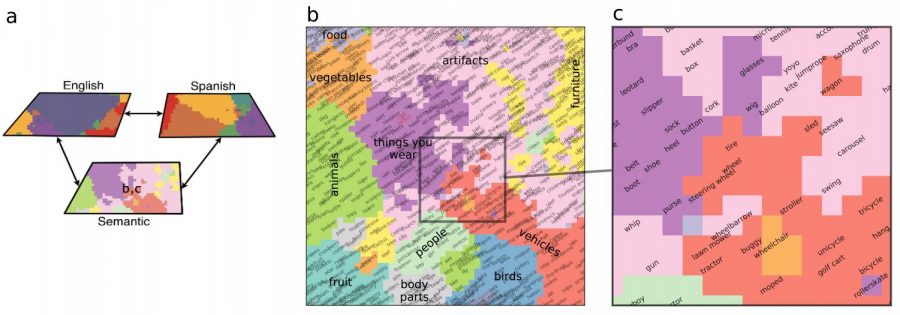

Uli Grasemann, a computer science research scientist at UT, said UT researchers then created a neural network model of the brain, which was able to simulate the brain’s response to therapy in English and Spanish. Combined with Kiran’s research, this could determine which language was more effective.

Kiran said she and her team have studied strokes and aphasia for over 20 years, hoping to improve a person’s ability to speak, read and write while experiencing aphasia.

“Before people even get (speech) therapy, can you say which language someone should receive the language in?” Kiran said. “If the therapist speaks English, they’re more likely to get therapy in English, and if the therapist speaks Spanish, then they will ask the patient if they want to get therapy in Spanish.”

Kiran said her team decided to work with Hispanic stroke survivors because there is an increasing population of Hispanic people in the U.S. that are underserved in treatments. Kiran said in the past, there have been situations where patients have received therapy in a language that is not the most effective for their recovery.

Kiran said the new technology is in clinical trials. If approved, they will then take the model’s predictions and treat the patients based on the language that will be relearned more effectively.

Risto Miikkulainen, a professor of computer science at UT, said in the future, the model could be customized more for each patient.

“It’s a part of a bigger future trend of personalized medicine, that we are not just treating everybody (equally), but we are looking at the individual makeup and personalized the treatment,” Mikkulainen said.