UT researchers create new technology to study tumor evolution

August 26, 2021

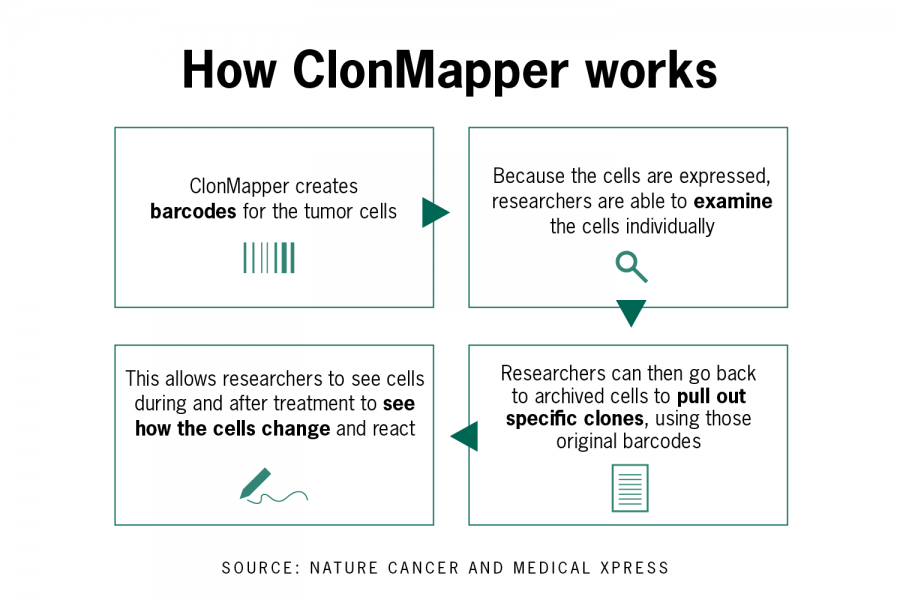

UT researchers have helped to better understand how tumor cells evolve to resist cancer treatments by developing ClonMapper, a new technology that tags the cells’ nucleic acid with a type of barcode.

By tagging the cells’ DNA with barcodes, lead researcher Aziz Al’Khafaji said researchers can now identify specific clones of cells to apply and test different drugs. He said researchers can then see how the cells react and monitor how they change.

“ClonMapper is this multifunctional tool that allows us to tag and track cancer cells and track their abundances over time,” Al’Khafaji said, “We can tell which particular clones or individual cancer cells that are more therapeutically resistant versus those that are susceptible to cancer treatment.”

Amy Brock, an associate professor of biomedical engineering, said ClonMapper has extreme potential because researchers can apply it to various tumors, such as acute biological leukemia, a cancer of blood cells, and cell types the team investigated.

While ClonMapper isn’t a cancer treatment, it has the potential to inspire new data and treatments, Brock said.

“Instead of just knowing how many cells died off with drug A versus drug B, we can really say this percentage of cells of this subtype were sensitive, but this other small percentage of cells really grew and became more resistant,” Brock said.

Tumors are consistently difficult to cure because different cell types can exist within a tumor, lead researcher Catherine Guiterrez said.

“Each patient can have a very different evolutionary trajectory from other patients with the exact type of malignancy, and so things can get very complicated,” Guiterrez said, “We wanted to dive into those differences between cancer cells and how those differences affect treatments and resistance to treatment.”

The research specifically focused on chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a cancer of the blood and bone marrow, because it progresses slowly, which allowed researchers to easily monitor how the tumor cells and their subpopulations changed over time, Guiterrez said. Researchers also chose this form of leukemia because treatment can be difficult, and there is a high chance of relapse for patients later.

“Most patients undergo what’s called a watch and wait period, where they’re diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and can undergo a prolonged period of monitoring before requiring treatment“,” Gutierrez said. “having that prolonged period of monitoring can provide us time to develop a nuanced understanding of how their respective tumors are changing and adapting to their environment.”

Brock said they also studied breast and colorectal carcinoma cancer but only released leukemia research. She said researchers have not released the information from these studies yet because they completed the leukemia study faster.

“We’re trying to kind of take a more targeted scalpel (approach) towards the disease,” Guiterrez said, “So the goal of this tool would be to see if we can take things a step further and be even more specific.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story stated that ClonMapper can be applied to breast cancer without patients needing to undergo cancer treatment. The story has been updated to say that ClonMapper can be applied to acute biological leukemia and that patients can undergo a prolonged period of monitoring before requiring treatment. The Texan regrets these errors.